| Sophie Durbin |

Phantom Thread plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema, from Friday, March 21st, through Sunday, February 23rd. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread tops my shortlist of “Unexpectedly Rewatchable Movies.” On the initial viewing, the film is obviously beautiful, perfectly acted, painstakingly art directed. And yet, it’s an enigma: what is going on with this freaky relationship? Why are these people treating each other this way? And (spoiler) why does it work out in the end?!! I suspect it could take a hundred viewings to get the whole picture. Those who watch it once and never again are likely to ask, “Why does Alma have no backstory?” Alma is kept almost comically mysterious: we never find out where she’s from, what she is doing working in that restaurant, why she is able to immediately upend her life to live with Reynolds Woodcock. A casual viewer may even say she’s underwritten, possibly in service of keeping the focus on Reynolds. I strongly disagree. On one of several rewatches, I realized that to really understand Alma’s role in the story, we must simply pay attention to a classic framing device at the very beginning of the film.

It’s easy to forget that while little of Alma’s backstory is shared with the audience, the entire film is told from her point of view. In the first scene she sits by firelight, speaking about her husband to someone offscreen. Is she being interviewed? Is she being psychoanalyzed? We eventually learn that she has been talking with Dr. Hardy, a country doctor who visits Reynolds after the first time Alma (spoiler!) poisons him. We return to the fireside couch scene occasionally as a reminder that the events we see are likely drawn from Alma’s memory—and possibly also through Dr. Hardy’s medicalized interpretation of her stories.1 The film is set in 1955, when psychoanalysis was all the rage. It is reasonable to assume that Dr. Hardy, while probably a general practitioner, may have been familiar with Freudian psychoanalytic theory2 or exposed to its basics as a recent medical student. (Anderson makes a point of including a moment where Reynolds mocks Dr. Hardy’s youthful appearance). This may explain why so much of Alma and Reynolds’s behavior is immediately recognizable from textbook psychoanalytic case studies: perhaps the young doctor has filtered the story according to the symbols he finds most potently Freudian. Allow me to walk you through some of these psychoanalytic artifacts in hopes that I can convince you what to make of Alma.

The intro of Freudian Psychoanalysis for Dummies3 includes an overview of the Oedipus complex, in which the son’s initial sexual impulses are directed towards his mother, and his first feelings of rage or hostility are directed toward his father. Part of a “normal” childhood is overcoming these instincts in order to fully separate from one’s parents. If that separation is botched, the son’s adult relationships will also be dysfunctional. Reynolds is a textbook case study of a man who failed to healthily move out of his initial dependence and attraction to his mother, now deceased. His every action is in response to his longing for her, particularly the act of dressmaking, which she taught him how to do. So: his career isn’t just his vocation—it is devotional. His very livelihood is a series of tightly controlled acts entirely dedicated to keeping her memory, and he spends his days adhering to a strict routine without which he cannot properly partake in this ritual. When Reynolds meets Alma, his first intimate gesture is to measure her and sew a dress for her. He entangles his romantic life with his work, and with his ongoing reverence for his mother.

Fundamentally incapable of functioning without a mother figure, Reynolds’s older sister Cyril fills in. His associations with Cyril have been entwined with his mother since long before her death: when he made her wedding dress for his mother’s second marriage, Cyril “came to his rescue” to assist with the sewing. (In the original screenplay, he explains that he used Cyril as “his first mannequin” for the dress form. Imagine: designing a wedding dress for a mother’s second marriage to a man he may have resented, using his sister as a model…will we ever get any relief from this Freudian onion?) Cyril doesn’t just manage the administrative aspects inside the House of Woodcock. She also breaks up with Reynolds’s girlfriends for him, is allowed into his private chamber even when Alma is not, and manages his social calendar like a mother would for her school-age son. Cyril takes the role that usually would be taken by an eventual wife. Freud wrote a lot about “incest dread”—that is, the near-universal taboo against parent/child and sibling sexual relationships. Here, Cyril and Reynolds have formed an arrangement that very nearly violates this taboo, and when Alma appears it seems she is there to intervene, freeing Reynolds from his dependence on his sister-mother. Of course, there are complications.

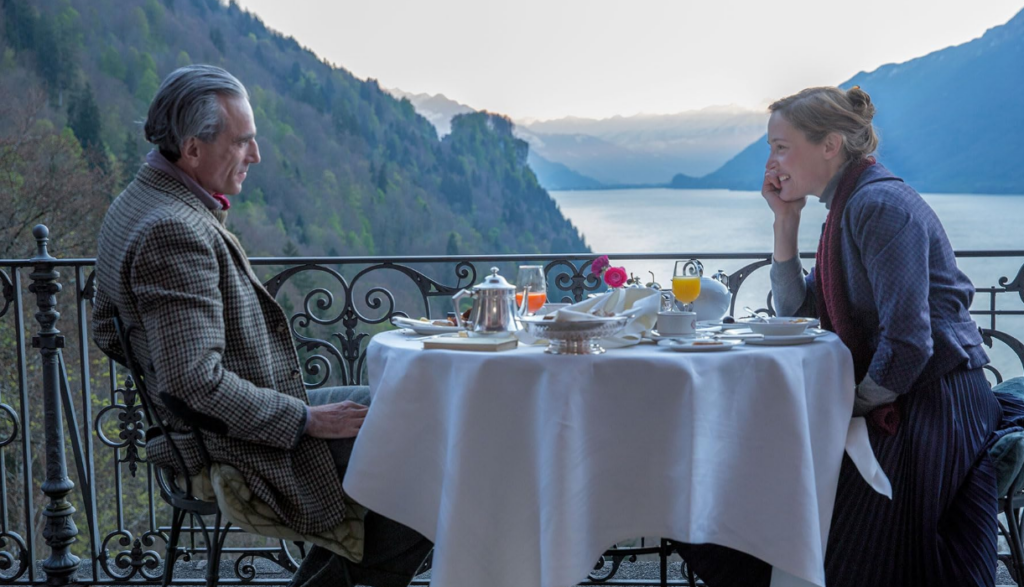

Shortly before Alma enters the picture, Reynolds shares with Cyril, “I’ve had the strongest memories of Mama lately. Coming to me in dreams, smelling her scent, the strongest sense that she is near me … reaching out.” The audience is primed for Alma’s arrival, and subtly informed of the role she will take in Reynolds’s life. He first meets her at a restaurant in the countryside, where she is working as a waitress. Alma trips and blushes (we see the blush actually spread in real time over Vicky Krieps’s face—thrilling!). Charmed when she comes to take his order, he requests nearly everything on the menu. The power dynamic is initially set up to make us think that it’s her youth or naivete that attracts Reynolds. But within moments, a strange energy moves over the table. It’s apparent that he is ravenous; Alma has stirred his appetite. He pauses, looks up at her, and asks: “What else?” His tone is childish, his hands are in his lap. The scenario is no longer a power play between an older man and a younger woman—it’s a young boy asking his mother for another snack. This theme recurs. When Reynolds is hungry, it is always wrapped up with desire. Reynolds’s sexual needs are wound up in his literal hunger, his need to be fed. It’s an immature association, a reminder of the primal connection to his mother that he never successfully severed. When he and Alma finally sleep together for the first time, it’s because she has noticed this linkage and chooses to seduce him with it: “Are you sure you’ve had enough to eat?”

Like I said, there are complications. Frustrated by her inability to be needed by Reynolds, and his refusal to modify any aspect of his entrenched routines for her, Alma discovers that she can access a more “tender, open” version of him when he is feeling ill (“like a baby,” she describes to Dr. Hardy). She takes full advantage of this knowledge by poisoning him with mushrooms so that he is incapacitated and utterly dependent on her care. Moved by this mother/son roleplay, Reynolds proposes to her and, after a few rocky months, is eventually fondly accustomed to being occasionally poisoned in order to “settle down a little.” In the final moments of the film, a flash-forward shows Alma pushing a baby carriage; this image is quickly dismissed as we return to the present, where no such child exists. Alma doesn’t need a new child to become a mother, because she has found balance in being both wife and mother to Reynolds himself. Distilled through Dr. Hardy’s vision or not, it’s a psychoanalytic case study for the ages.

Footnotes

1 I’ve found ways to write about Vladimir Nabokov for Perisphere a few too many times, but I will cite a more famous example of this narrative technique. In Lolita, Dr. John Ray writes the introduction and presumably all of Humbert Humbert’s story has been filtered through him. In both Lolita and Phantom Thread, this device is deployed at the beginning and remains mostly hidden throughout the story, making it easy to forget that the narrator may be bending the “facts” according to their own bias.

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychoanalysis will give you some context but those interested in digging deeper may look at two volumes I consulted for this piece: The Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud and Basic Writings of Sigmund Freud. Also, I’m not the first person to think about Phantom Thread using a psychoanalytic lens: see https://brownuniversitypsychoanalysis.wordpress.com/2018/05/11/recap-a-psychoanalyst-goes-to-the-movies-unpacking-unconscious-content-in-phantom-thread/ for another angle.

3 Doesn’t exist, but should. Also, Freud never really clarified what he thought of girls’ own Oedipus complexes—he wasn’t a fan of the “Electra complex” proposed by his student Carl Jung.

Edited by Matthew Tchepikova-Treon