| Allison Vincent |

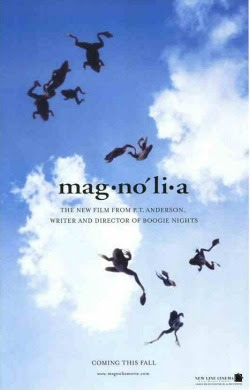

Magnolia plays on glorious 35mm from Friday, March 7th, through Tuesday, March 11th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Why Magnolia So Fully Captures the Ennui of the End of the 20th Century

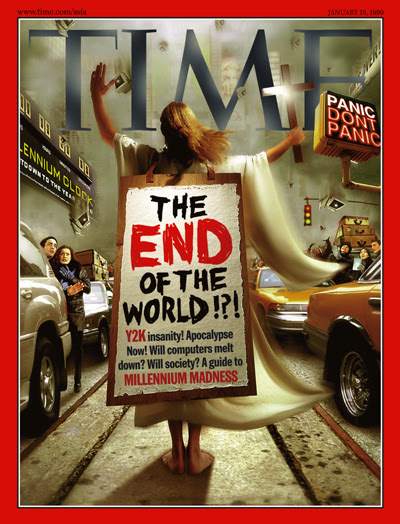

I need to start this post by explicitly stating that I am a millennial. Trust me, it’s important. Technically, because I was born in 1987, I’m an “elder” millennial or geriatric millennial if you’re trying to be rude about it. There was a meme/theory floating around the internet a while ago that marked Shrek as the end of millennial childhoods, as the last time we, as a generation, were happy. A few months after Shrek premiered in April of 2001, the September 11th terrorist attacks happened and changed everything, including our little pre-teen lives, forever. The impact of 9/11 was so great that it virtually wiped out all memory of what should have been the major nervous disorder trigger for most of us: Y2K.

Remember that? From the mid-90s up until the very last second of December 31st, 1999, the entire world was unsure about whether life, specifically our digital lives, would go on as usual or if everything would blink out of existence. Doomsday cults and fundamentalist fanatics were preaching the end times, preppers were getting their moment in the sun, and rowdy boy anti-government white nationalism was on the rise. Gen Xers, like Paul Thomas Anderson, were left watching with grim, detached horror masked as “too cool for school” indifference, wondering, “Wait, what are we supposed to do?!” Magnolia is a sort of gentle hug for my cultural big siblings. The film seems to acknowledge that, yes, this is all so unbelievable and unfair, and, yes, our parents so royally fucked us and the world up, but what are we going to do? Give up? Try and change things? Make the future better for ourselves?

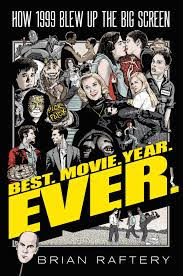

As Brian Raftery’s excellent book, Best. Movie. Year. EVER: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen, notes, Magnolia carried the immense pressure of following P. T. Anderson’s hit 1997 film Boogie Nights, which had set him up as the end of the decade’s next moody, eccentric, white guy wunderkind a la Quentin Tarintino. In this blissful moment of cinema, several smaller and midsize studios had money to throw behind the next big niche thing that would grab the attention of smart, genre-savvy moviegoers hungry for something new. This is in immense contrast to the current mega studio mass appeal world we generally live in now. New Line Cinema picked up Anderson’s next project and essentially gave him carte blanche and a shit load of cash to do whatever he wanted. The result is a gorgeous, well-funded, abstract mosaic of a film. By every measure, it was never going to be a blockbuster, but did seem artsy enough that it might snag significant awards or the hearts and minds of the Gen X cinephile looking for the next generation-defining film.

The movie is long, boasting a staggering three-hour and eight-minute runtime, and demands the viewer zoom out and drink it in as a sum of all its parts. In many ways, Magnolia feels like a play. We follow several different storylines that eventually merge through either action or theme, commenting on how this disparate group of characters are all on the brink of epiphany about their lives, failures, and parental relationships in generally the same place, at the same time. For me, the “music video” moment where Aimee Mann’s “Wise Up” plays as each character sings along to the track in their most downtrodden reflective moments demonstrates that- we’re all alone in crisis together, singing the same sad song about needing to get our shit together.

The mounting pressure in each character’s life comes to a head on this one strange night in the San Fernando Valley. It feels a lot like the possible cliff the audience was steadily marching towards at the tail end of the century, with the possible collapse of digital society lurking at the cusp of the new millennium. Anderson was putting his finger on a very important pulse of the moment. Despite this very big, very scary, seemingly real thing looming, we are all also still mired in our own stupid lives. Yes, the world is ending, but I also think I might hate my dad, or I’m afraid I’ll die alone, or I’m not sure I’ve ever been truly loved, or what if I’m a fraud. Even in the face of unprecedented events, the biggest force of change in our lives is our relationships with one another. It’s a beautiful, profound observation. But, not all critics and moviegoers felt the same tender appreciation I do: “Like the plastic bag scene in American Beauty, the “Wise Up” sequence would split critics and moviegoers–some saw it as an indulgence, others as a moment of uneasy harmony among discombobulated souls. But the sing-along was nowhere as divisive as what followed” (Raftery 2019, 301). At the climax of the film, when things are most dire for all the humans inhabiting this tangled storyline, frogs fall from the sky.

Aside from the biblical symbolism of things raining from the sky that simply should not, and a bunch of frogs showing up, it doesn’t make sense. And that’s the point. Life doesn’t always make sense. Even though it’s supposed to, even though it should. The world of structure, cause and effect, right and wrong, good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people our parents promised us doesn’t really exist. For P.T. Anderson, the frogs represented trying to conceptualize his father’s impending death from cancer: “‘I remember talking to an oncologist on the phone who was essentially telling me that there was no way my dad was going to make it […] And one of the first things that popped into my mind was ‘You’re telling me frogs are falling from the sky.’ Hearing your dad is going to die is as bizarre as hearing frogs are falling from the sky’” (Raftery 301). Are frogs falling from the sky any harder to accept than the multitude of cruelties we each have to face in any one of our simple little lives? Anderson’s answer is, “No,” which is why there is no explanation offered in the film despite the prologue’s narrator begging that there can’t be such “coincidences” in life.

The narrator, who we only heard in the prologue, returns briefly in the “So Now Then” section right before the film’s conclusion to remind us of the three morbid examples of gruesome coincidences we saw in the prologue. He adds, “Well, if that was in a movie, I wouldn’t believe it,” and repeats that “it is the humble opinion of this narrator that strange things happen all the time. And so it goes, and so it goes, and the book says we may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us” (Anderson 1999). The narrator may not want to believe that coincidences, even the most brutal, unbelievable coincidences, do happen at random with no value, moral, or reason attached to them, but the characters of the movie accept the frogs as just some weird thing that happened.

Human beings are generally bad at accepting incidents like this. We are programmed to search for meaning, to pursue fulfillment in life, to have a purpose, and I think that is why the narrator’s second interruption in the film hints at literary references that may help the viewer process or rationalize the frogs. “The book” the narrator cites could be Exodus 8:2 from the “big book,” the Bible: “And if thou refuse to let them go, I will smite all thy borders with frogs.” This seems like a strong contender for obvious reasons, but I also think the repetition of “So it goes” clearly invites Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse V into the chat. Here, “So it goes” means both “life goes on,” and “death is inevitable” phrased in such a playfully casual way that it diminishes the towering certainty of our inevitable demise. How very Gen X. This view is best summarized by “The years start coming, and they don’t stop coming” for my Shrek/Smash Mouth-loving Millennial friends.

I mean, what are two things most people turn to when life throws them a curve ball? Religion and art. But, as the movie’s end reveals, it’s connection that will ultimately save us. The point is quite literally made as Aimee Mann’s “Save Me” plays over a slow zoom of Claudia sitting in a bed as Officer Kurring returns to try and tell her, in dialogue we’re barely able to hear over the song, that she’s a good, beautiful person, and he would like to help her. The film ends with Claudia smiling at the camera through tears. By finding the people who love us for who we are, letting go of the people we cannot change, and forgiving those who did us wrong but did their best, we can face whatever is coming down the pike. Together we can weather any storm, even if it rains frogs.

This particular feeling of helplessness/whateverness/slowly riding the conveyor belt toward destruction a la Toy Story 3 Anderson captured at that watershed moment of 1999 on the precipice of disaster feels remarkably prescient for our current climate. If frogs were to fall from the sky today, I’m not sure I would be that surprised myself. Obviously, this moment is markedly worse in terms of scale and threat to humanity, but there’s a similar feeling. A numbness. A hopelessness. A sense of being cheated out of a life promised to us. But also a desperate desire to find community; to not be alone.

So it goes.

Bibliography

Magnolia. United States: New Line Cinema, 1999.

Raftery, Brian. Best.movie.year.ever.: How 1999 blew up the big screen. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Rothman, Lily. “New Year’s Eve 15 Years Ago: How We Prepped for Y2K.” Time, December 31, 2014. https://time.com/3645828/y2k-look-back/.

Snob, Culture, Edward Copeland, Caroline, Bob, Tague, Cad, Zoe Kerns, et al. “Why Are There Frogs Falling from the Sky?: Culture Snob.” Culture Snob | Commentary on Pop Culture by Jeff Ignatius, March 8, 2024. https://www.culturesnob.net/2007/05/why-are-there-frogs-falling-fr/.

Toy Story 3. DVD. WaltDisney, 2010.

Edited by Matthew Tchepikova-Treon