| Brogan Earney |

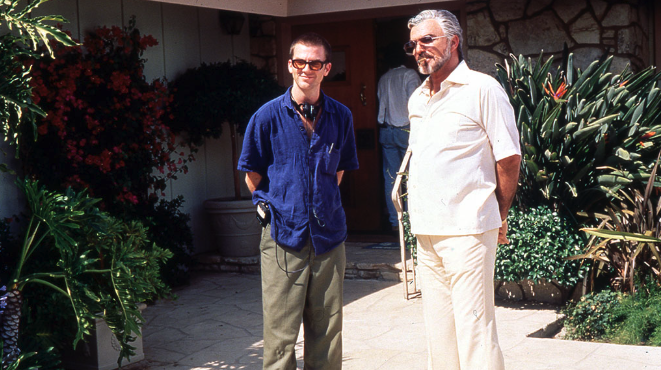

Paul Thomas Anderson, then just 27 years old. Directs the pool party on a 100 degree day in the Valley.

Boogie Nights plays in glorious 35mm from Friday, February 28th, through Tuesday, March 4th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

“I have seen the new Quentin Tarantino, and his name is Paul Thomas Anderson,” wrote Entertainment Weekly’s Owen Gleiberman after watching the premiere of Boogie Nights at the 1997 Toronto International Film Festival. It was a line that recognizes the achievement of the film as well as the master at work behind it, and it was all part of the plan. Then a 26-year-old filmmaker with only one feature-length credit to his name, Anderson was given the keys to the castle and he proved worthy of it. The $15 million budget for Boogie Nights was a direct response to the success of Pulp Fiction. New Line Cinema was the studio behind Boogie Nights. After passing on films like Reservoir Dogs and Kids that decade, Mike De Luca of New Line Cinema was not going to repeat the same mistake. Betting on a high-end return on investment, Boogie Nights had the opportunity to make major waves in the independent cinema world and provide yet another soundtrack album with huge sales potential during an era of maximum synergy. It achieved both, and much more.

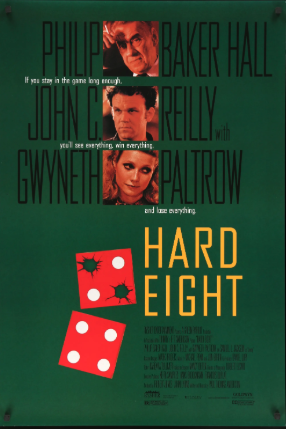

Hard Eight, released in 1996, was a commercial flop but critically well received. Paul originally wanted the film to be titled Sydney and based it on another short he made, Cigarettes & Coffee.

Though not technically his debut feature film, you could argue that Boogie Nights is a better representation of PTA’s filmmaking style than its predecessor, Hard Eight. Released in 1996, Hard Eight proved to be a nightmare experience for the first-time director. Rysher Entertainment made major alterations to the final product without PTA’s consent, including significantly reediting the film, along with cuts that altered its pacing and narrative structure. They even changed the original title from Sydney, which I think was probably a good decision. This experience led to PTA storming into the New Line Cinema meeting and demanding full creative control and final cut. Which De Luca was happy to provide after reassuring him that New Line would honor his vision. What was the root of all this faith given to this young director? Fundamentally, it was PTA’s 185 page script for Boogie Nights, which eventually landed him an Oscar nomination for “Best Original Screenplay.” Beyond that, it was the highly detailed, intimate knowledge the artist had for the American porn industry of the 1970s.

The Dirk Diggler Story was a 30 minute short that Paul made with a few of his friends. The story mimicked that of John Holmes. Paul’s dad did the voiceover on the film.

PTA grew up in the San Fernando Valley, where most of the film takes place, during a time when adult film production existed as a marginalized yet omnipresent part of the film industry, leaving quite an impression on his young imagination. “As a kid, I was surrounded by these porno shoots,” Anderson said in a 1999 article he wrote for the New York Times. “The area of Van Nuys where I went to high school had warehouses, and each warehouse would have a sign hanging out front. Every fourth warehouse or so would be without signage and would have fancy cars parked out front. This, in my perverted mind, meant one thing: there’s porno in there. And I was right. If you’re precocious, young and randy, the valley can be an interesting place to live. If what informs your youth is channeled well, you can end up making a movie about porno as opposed to making porno. I think I got lucky.” The passion first culminated in a mockumentary short titled The Dirk Diggler Story that Anderson filmed with the help of his father and friends in 1988. Pulling from films like Spinal Tap and the John Holmes documentary, Exhausted, The Dirk Diggler Story follows the rise and fall of well-endowed male porn star Dirk Diggler in a fictitious portrayal of actual porn star John Holmes. The short made its rounds in Hollywood and sort of gained a cult-like reputation. This DIY short and PTA’s script combined were a good enough preview for what New Line was going to get with Boogie Nights. For Anderson it was a great opportunity to make his mark in the industry, with a project that fits his interests and that’s personal to him. A director using their own world experience and background as a blueprint for their first film is a common practice. Anderson making Boogie Nights reminds me of Damien Chazelle with Whiplash or Greta Gerwig with Frances Ha. Us viewers can detect the sentimentality for the subject and can be introduced to a world that only the directors can take us to. PTA was very committed to making his portrayal of the film industry as accurate as possible. Himself and some other crew members would hang around porn sets for a full year, observing and becoming familiar with the methods in which the art is created. They even were able to acquire famous porn star Ron Jeremy as an on-set consultant.

Paul stands with Burt Reynolds outside of the Valley house. The two notoriously didn’t get along as Burt was difficult to work with and thought that PTA was just a cocky kid. Burt ended up receiving an Oscar nomination for his work in Boogie Nights.

Like Anderson says in the article he wrote himself, he luckily never had to make porn. That being said, what would be his in for Boogie Nights if he can’t relate to a porn star? Well, he can relate to being a young boy from the valley who believes that he is meant for great things in a challenging industry. If you watch the movie in that light, you can see Anderson’s persona leaking from Eddie, who is portrayed by Mark Wahlberg. In a great early scene, Eddie gets into a heated conversation with his mother: “You don’t know what I can do, what I’m gonna do, or what I’m gonna be! You don’t know I’m good!” It’s almost as if Anderson is channeling his own feelings towards his upbringing or even towards Hollywood, or more specifically Rysher Entertainment. Luckily, PTA didn’t end up having the same outcome as Eddie did, and he was able to get out of his own way to achieve success. Boogie Nights is filled with overt references to films that inspired PTA’s vision and taste, including On The Waterfront, The Sweet Smell of Success, Raging Bull, Touch of Evil and I Am Cuba. The film begins with an impressive one-shot that leads us through the “Hot Traxx” nightclub, a shot that took 12 days to shoot and resembles the infamous Copacabana one-shot from Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas. Not only does it resemble the shot, but it was also manufactured to be the exact same length as the Copacabana shot. It’s a shot that demands the attention of the audience and lets you know that a new cinematic voice is here. Boogie Nights went on to nearly triple its budget at the box office, as well as receive three nominations at the Academy Awards. But more importantly it sparked the career of one of the most vital voices in American cinema. The success gave PTA the green light to make one of the greatest blank check movies, Magnolia, and since then he has gone on to write and direct six other films. The road to creative control may have been difficult, but it paid off and has allowed PTA to continuously create new and interesting projects throughout his career. His next project is due to arrive this Fall. To prepare for that, I’d recommend seeing Boogie Nights and all the rest of his films in the coming weeks at The Trylon!

At the end of the film Eddie gives himself a pep talk in the mirror before his first big scene back. This scene pays homage to both Raging Bull and On The Waterfront.

Sources

Paul Thomas Anderson, “Paul Thomas Anderson: A Valley Boy Who Found a Home Not Far From Home.” New York Times, November 14th, 1999. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/film/111499anderson-film.html?scp=66&sq=%2522Boogie%2520Nights%2522&st=cse

Alex French, Howie Khan, “Livin Thing: An Oral History of Boogie Nights.” Grantland https://grantland.com/features/boogie-nights/

Adam Nayman, “The Masterworks of Paul Thomas Anderson.” 2020

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon