| Courtney Kowalke |

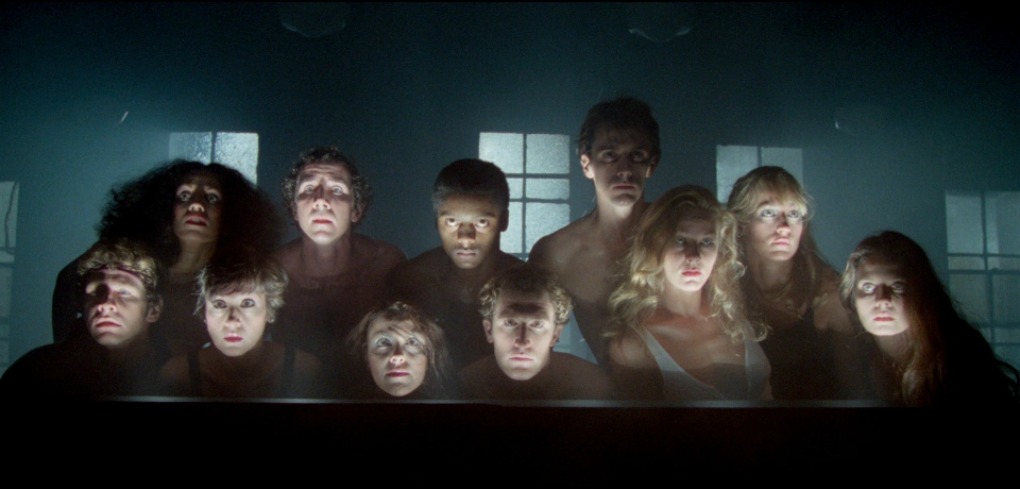

Image sourced from Internet Movie Database

All That Jazz plays on glorious 35mm from Sunday, January 26th, through Tuesday, January 28th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

The day after Perisphere assigned me All That Jazz (1979) for my next film essay, the web browser on my phone recommended I read the IndieWire article “‘All That Jazz’ Is a Favorite of Fincher, Kubrick, and Scorsese—Here’s Why.” I’m not a fan of whatever spyware made that happen, but it made for a good jumping-off point. Bob Fosse only directed five films, yet he is venerated by some of the greatest American filmmakers. Why is that?

The answer is the marriage of All That Jazz’s form with its themes. It’s a movie musical, flashy and colorful and full of song. The songs and dances themselves, however, highlight “its creator’s insecurities, cruelty, contradictions, and self-absorption with no filter and no mercy” (IndieWire). Writer Joe Hemphill further cites this unflinching honesty as an asset of the film: “To call [All That Jazz] autobiographical is like calling ‘Psycho’ a movie about a guy with a few mother issues. ‘All That Jazz’ is so nakedly exposing of its writer-director’s neuroses —and so filled with obvious references to his real-life work and relationships—that it makes [Federico Fellini’s] ‘8 ½’ and [Woody Allen’s] ‘Stardust Memories’ look withholding and complacent” (IndieWire).

The article maintains an air of awe that amuses me. Hemphill seems surprised by Fosse’s impact and by Fosse’s mastery of his craft. I’m not. Since I was seven years old, I have been interested in musical theater. If you know musical theater, you know Fosse. (Don’t worry—I didn’t find his work until I was twelve.) Fosse revolutionized Broadway choreography. Everything in a dancer’s body mattered to Fosse, from the angle of your knee during passé to the curvature of your spine in arabesque penché, from the roll of a wrist to a cock of the hip. Fosse wanted everything to mean something. He wanted the human form to further express the intention of his stories. (The thin forms, anyway—I took ballet lessons for fifteen years and have never been more aware of how out-of-shape I am currently than when I was watching Leland Palmer do body rolls.)

Image sourced from Film School Rejects

Fosse wasn’t a perfectionist. He was the perfectionist. Every little detail had to land exactly the way he wanted it to. Fosse brought that energy to every project he worked on, so it’s no surprise that while he was simultaneously editing Lenny—Fosse’s first film after he won the Academy Award for Best Director for Cabaret—and directing and choreographing Chicago on Broadway in 1974, Fosse had a heart attack that required immediate open-heart surgery. The operation was a success, but the experience gave Fosse some new food for thought. In a 1981 Criterion interview about All That Jazz, Fosse explained:

Well, it’s, the history of [All That Jazz] is odd because I was in the hospital myself… I had a heart attack and open-heart surgery. And I became very interested in death and hospital behavior and the meaning of life and death and those kinds of subjects, and so I started working with a friend of mine, a writer by the name Robert Alan Arthur, on the screenplay of a of a novel called Ending by Wilma Hollis. And it was… about a woman whose husband was dying and her problems with the children, her problems about money, her sex problems, etcetera, and it was… We got a screenplay, and it was a beautifully-written screenplay, but it was it was just so down, and every day I’d go to work, and I’d say, “It’s a lovely piece of material but I’ve got to spend a year-and-a-half with this to two years, and I don’t think I can face this kind of material… And I said, “I like the subject and I would really like to do something in the same area, but with the tools I can use best, which is song and dance…”

(Sidebar: I tried my damndest to find any kind of information about the book Fosse mentioned adapting, but I couldn’t find mention of it anywhere on the Internet.)

Fosse certainly made the story his own. Everything in All That Jazz means something. Everything has a direct, one-to-one correlation to Fosse’s experiences in 1974. Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) is Bob Fosse, Audrey Paris (Leland Palmer) is Fosse’s estranged wife and fellow choreographer Gwen Verdon, The Stand-Up is the film Lenny, and NY/LA is the musical Chicago. I have to give flowers to my personal favorite actress Ann Reinking, who plays Kate Jagger, a dancer who is having an affair with Gideon and whose real-world counterpart was Reinking herself. Nobody is doing it like her.

Image sourced from Criterion Collection on Instagram

If I were put into Reinking’s position, I would melt. If I were in Fosse’s position, I would melt. I am capable of self-reflection, but would I detail my flaws and then hire people (some of whom are long-time friends, lovers, and colleagues) to act out my worst moments and then put them up on the big screen for an even larger audience? I spent most of last Saturday holed up in my bedroom because an old woman yelled at me for throwing a pinecone my dog was trying to eat into her yard, so I’m going to go with, “No.” I can’t handle criticism from my neighbors. I couldn’t handle criticism on the world stage.

Going in to All That Jazz, I thought a creator would need to be either brave and audacious or stupid and self-involved to make a film about their own breakdown. In practice, I suppose it depends on how precious the person is about what they went through, how important they find their own life.

Even when the subject matter is himself, Fosse pulls no punches. “No, nothing I ever do is good enough,” Gideon laments halfway through the film. “Not beautiful enough, it’s not funny enough, it’s not deep enough, it’s not anything enough. Now, when I see a rose, that’s perfect. I mean, that’s perfect. I want to look up to God and say, ‘How the hell did you do that? And why the hell can’t I do that?’”

Fosse’s frustrated pursuit of perfection is at the heart of this dialogue. When interviewed by Barry Rehfeld for Rolling Stone in 1984, Fosse said, “I know I’m good, but [fellow choreographers George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins] talk to God. When I call God, he’s always out to lunch.” Fosse was willing to work himself to death to ‘talk to God,’ to make his vision real. “I always thought,” Fosse told Rehfeld, “this was the way to do important things. If you’re not willing to put your life on the line, how can you do important things?”

I’m not a saint. I have made big mistakes, mistakes I have lost sleep over and wished fervently that I could take back. I still want people to think I’m a good person, though. If I made a movie about myself, my thesis statement would be, “She was misunderstood and deserved better,” whether I did or not. I still want to be the hero. Fosse’s thesis statement in All That Jazz is “I understand why I deserve to die alone.” There is brutal honesty, and then there’s this. Most people want to be the hero, but Fosse doesn’t care for the role. Looking back at his life and career, Fosse says, “What I did was wrong and I’m not sure the results were worth all the pressure I put on the people around me.” I admire him for that. Not everyone is willing or able to reevaluate their beliefs like that.

Image sourced from Indiewire

All That Jazz provided me with a great metaphor for my feelings on self-reflection as well. Roughly half an hour before the end of the film, Gideon goes in for his surgery. You get to see it all. The retractor in Gideon’s chest cavity is pulled open, showing his beating, bloody heart. I don’t consider myself that squeamish, but I was watching this through my fingers. I had trouble hacking it, the way I struggle with baring my soul to other people. Fosse doesn’t have a problem with it. He’s going to go above and beyond opening a vein and bleeding onto the page to establish contact with his audience. Fosse goes big or he goes home. That’s all he knows, and I and many other directors and choreographers and artists admire him for that.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon