| Jillian Nelson |

Working Girls X3! plays at the Trylon Cinema for one day only on Saturday, January 18th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

During the summer of ‘92, right before her senior year of high school, my mother moved out of her parents’ home and into her great aunt’s basement, which she rented for fifty dollars a month. Her senior year she paid for everything on her own: school supplies, sports equipment, food, clothes, tampons, hygiene, and beauty products. In between jobs, her eyes searched the bus stop pavement for change to buy food. In the spring of ‘93, she became pregnant with my older brother. To support herself and her baby, she worked odd retail and office jobs while attending college, following her ambition to become a postpartum nurse. Enduring and brave, my mother embodied the working girl’s life.

Her story emerges alongside the strong women highlighted in the Working Girls triple feature. These feminist films follow working women who navigate societies that attempt to control their economic, sexual, and social freedom. The hardship these women face doesn’t define them as they stoically pursue liberation. Harnessing female friendship, joy, imagination, and Marxist action, they challenge capitalistic and patriarchal oppression.

Women Dancing Hand In Hand

Dorthy Arzner’s Working Girls (1931), set during Depression-Era America, centers June (Judith Wood) and Mae Thorpe (Dorothy Hall) who move from Indiana to New York City to hunt for jobs and men. This sister duo faces a repressing cultural message that pains my queer hands to write: heterosexual marriage is the only way for women to gain economic and social mobility. The film depicts their experience of the conflict between the time’s rising, a new concept of the independent woman, and patriarchal obstacles.

The film’s focus on female friendship and sisterhood undermines society’s reliance on heterosexual relations for social belonging.1 The boarding house that June and Mae move into becomes the film’s central hub of female connection. Here, women cleverly defy the manager’s strict, moral code. Outwitting the rule that one must sign the book every time they stay out overnight, one sly woman winks when she “visits her aunt” each Saturday. In another scene, women dance together, inviting the viewer to imagine romance as they sway, hand in hand. Arzner’s inclusion of these queer, feminist moments structures the boarding house as a rebellious, liberating space where women transgress heteronormative boundaries. Through a wink and a dance, she challenges her culture’s attempt to confine female sexuality and social connection to just marrying a man.

Image sourced from Pre-Code.com

Marxist Capitalists and Naked Humor

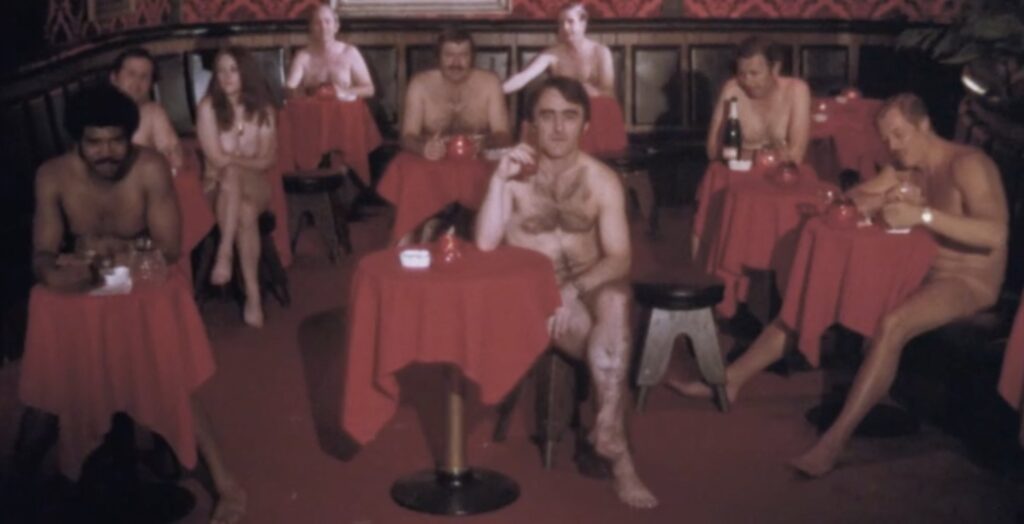

Taking inspiration from Depression-Era films, Stephanie Rothman’s The Working Girls (1974) follows three young single women rooming together in Los Angeles as they perform odd jobs to survive the stagflation-riddled 1970s American economy. Jill (Lynee Guthrie) works as a cocktail waitress to support her law school career and ambition to become a Supreme Court Justice, recent college graduate Honey (Sarah Kennedy) freelances as a paid companion to a greedy millionaire, and Denise (Laurie Rose) balances her passion as a nude artist with a second job painting billboards. These three women face patriarchal forces that don’t take them seriously, exemplified through the separate men they each encounter. Rothman captures the time period’s motionless tone through the setting’s openness. As Honey searches for a job, she wanders through non-descript, endless streets and office buildings. Rejected and locked out, she has nowhere to turn. However, in her quest for financial freedom, Honey liberates herself from capitalistic structures. Rather than hoard the money like her boss, she distributes a portion of her earnings to her friends.

The agoraphobic atmosphere also creeps into Jill’s workplace where men watch the waitresses and performers move through the vast bar and open stage. Rather than recreate the bar’s voyeuristic viewing relation, Rothman cleverly uses the exploitation film to challenge its own form. During her first strip tease, Jill pauses over her clothing, pinned under the mostly male audience’s peeling gaze. Nowhere to hide, she starts cracking under pressure until Katya, her mentor, reminds her of the stripper’s secret weapon: imagine the audience naked. Closing her eyes, her mind enters a realm beyond the men’s control. Upon opening, the film cuts to her audience completely naked. She strips the men of their power, freeing her body and mind. In a following close-up, Jill looks directly at the film audience, placing us at the same level as her hecklers. Her smile blurs the line between performance, joy, and mocking, encouraging a disrupting moment that recognizes viewership. Caught in the act, Rothman strips the film audience of their power over Jill. Harnessing humor and irony, she questions the exploitation film’s traditional viewing relations, creating a moment of female reclamation and liberation.

She Performs Labor

Working girls work?! The redundancy! Even so, the blatant message that women do indeed work is precisely the driving force in Lizzie Borden’s Working Girls (1986). She immerses the viewer in the transaction-driven culture of mid-eighties New York City through the sex worker’s perspective, bringing the physical and emotional labor they perform into hypervision. To fund their ambitious pursuits, Molly (Louise Smith) and her fellow workers traverse a Manhattan brothel. Lucy (Ellen McElduff), their boss, exploits their labor and dictates their action, reducing their personhood to a seamless commodity.

The camera lingers on their workday’s ordinary demanding details. A close-up of Molly’s feet as she slips her shoes on before her first client, stepping into performance. A slanted angle of Gina’s hands and forearms attempting to grip the edge of the bed. Observational scenes of them washing up after each session, period blood squishing out of Gina’s contraceptive sponge. These women also produce emotional labor, countering Molly’s own rebuttal to Dawn’s request that she write her an essay, “I’m already selling my body, I don’t want to sell my mind.” They manage the telephone, take appointments, play girlfriend, get clients’ drinks, ask them about their day, give dating advice, remember details said during a previous session to ask about again. Ring Ring! “What’s new and different?” Ring Ring! “Make yourself completely comfortable.” Ring Ring! “We have a variety of girls today.” Knock Knock! Buzz! Ring! Rin- “What’s new and different?” Kno– “I thought you’d be in a brandy mood.” “I’m not going to do anything I don’t want to do” “Please hold.” “Please hold.” “Please hold.” Borden sews these visual and aural snippets together, creating an overwhelming, mechanical rhythm they must manage. This takes its toll on Molly, pushing her boundaries and causing her to break down.

Within the brothel’s transactional, confined space, these women find moments to defy its metronomic drudge. Free from Lucy’s pressing eyes, they order lunch, speak openly about their ambitions, and lounge about the reception area. Frequently writing their full sessions in as halves, they reclaim some of their surplus labor that Lucy freely exploits. The most visually open scene in the brothel occurs when Molly, Dawn, Gina, and an unnamed woman rebelliously pass around a joint. They all burst out laughing and the screen cuts to a high-angle shot allowing the viewer to see all four of them at once. Their laughter produces an air, a freeing space that expands upwards towards the ceiling and threatens to breach the apartment’s pristinely painted walls. Molly breaks them down herself by quitting. So Mayer brilliantly argues that Molly’s Marxist action reclaims her economic value from Lucy, placing it back in herself.2 Biking home through the open air, she smiles, liberation lifting in the corners of her lips.

Between Past and Present Working Girls

As I watched and read about these three films, the women on screen, their stories and their themes, transgressed the boundaries of space and time. They began to speak to one another. Laugh together. Cry together. Glimpse at one another through a mirror or over the shoulder. They began to transgress the screen itself, representing real working girls, like my mother. While each woman contains their individual, multidimensional story, bringing their voices together allows a connection to form between them. This makes their stories visible in the archive, asserting that brilliant women have and continue to work, struggle, and dream of a brighter, liberated future. In remembrance of working girls’ past and present collective lives, I end with a visualization of a brief passage from Vera Caspary’s Music In the Street, a novel that inspired the play Blind Mice that in turn inspired Zoë Akins’ screenplay for Arzner’s film.

“There are girls with avid, searching eyes and girls dull with the discontent of long office days ahead,…”

Images from Arzner’s Working Girls are sourced from Pre-Code.com

“…girls rebellious because they have only impersonal business hours to contemplate, and girls eager because an office and its men and its activities is a better place than the kitchen…”

“…There are girls tired because they been awakened by raucous-voiced alarm clocks after insufficient sleep; girls hungry because they rose too late for coffee and breakfast food…and timid girls wondering if they shall have to suffer this morning for yesterday’s errors.”3

Resources

1. Gwendolyn Foster, “Pre-Code Women: Dorothy Arzner’s Working Girls (1931),” Sense of Cinema, February, 2017, https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2017/cteq/working-girls/.

2. So Mayer, “Working Girls: Have You Ever Heard of Surplus Value?,” Criterion Current, July 13, 2021, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7461-working-girls-have-you-ever-heard-of-surplus-value?srsltid=AfmBOoq6q2rptb7pqokp6LrpCdlFEhwrPsF082P4L5QSpbpy-ovH6V5k.

3. Vera Caspary, Music in the Street (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1929), pp. 151- 152.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon