| Steve Rybin |

Equinox Flower and Late Autumn will be playing on glorious 35mm film at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, December 13, to Sunday, December 15, and from Friday, December 20, through Sunday, December 22. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

The Trylon’s “Ozu in Color” series presents four of Yasujirō Ozu’s color films made near the end of the director’s career (1958 to 1963). These films cover what is for Ozu familiar narrative ground: fathers and mothers give away daughters to marriage; generational conflicts pit youngsters against tradition; and parents and grandparents contemplate the inevitable passage of time. Nevertheless, despite such thematic recurrences, we should be wary of assuming Ozu will ever conform to expectations. As Shiguéhiko Hasumi argues in his book Directed by Yasujiro Ozu, Ozu wants us to always “keep our eyes on the films” (296), staying attentive to what is surprising and unexpected in his work. In fact, Hasumi urges us to avoid the word “Ozuesque” to describe Ozu, because the familiarity it implies suggests the director only offers expected comforts. With the films in this series, following Hasumi’s wise directive means keeping our eyes on Ozu’s playful use of color.

Equinox Flower, Ozu’s first work in color (and the second in the Trylon’s series), is about a father, Wataru Hirayama (Shin Saburi) who protests his daughter Setsuko’s (Ineko Arima) refusal of an arranged marriage. Near the beginning of the film, though, Hirayama extols the virtues of more modern forms of marriage in a speech he gives on the occasion of the wedding of Fumiko (Yoshiko Kuga), the daughter of his friend Mikami (Chishū Ryū). Hirayama’s eloquent words may contradict his later objections to his own daughter’s interest in following a similar, independent path, but the film doesn’t smugly or simply characterize Hirayama as a hypocrite. Like many characters in Ozu’s world, Hirayama’s contradictions reflect his own complex navigation of the changing textures of postwar Japanese life and tradition, as well as his own experiences, expectations, and regrets.

Equinox Flower is a delightful introduction to how Ozu uses color. Plenty of films encourage us to think about color symbolically, to search for conventional and familiar meaning in color (“red is passion,” and so forth). Ozu, though, utilizes color in a way that, very much like psychologies of his characters, cannot be reduced to conventional or expected interpretation. Filmmaker Kijū Yoshida notes in his book on Ozu that “Ozu-san regarded the representations in cinema as chaotic. He hated viewers who insisted on their selfish viewpoints. He warned that cinematic expressions are merely artificial, and he kept playing with them” (133). Ozu’s use of color, like other aspects of his style, challenges viewers to remain perceptually open to the complex and, as Yoshida suggests, even chaotic everyday worlds represented in his films. Ozu invites us to linger with the colorful impressions of his films, resisting any urge to assign immediate meanings to color (or to become the kinds of viewers with “selfish viewpoints” that Yoshida claims Ozu despised).

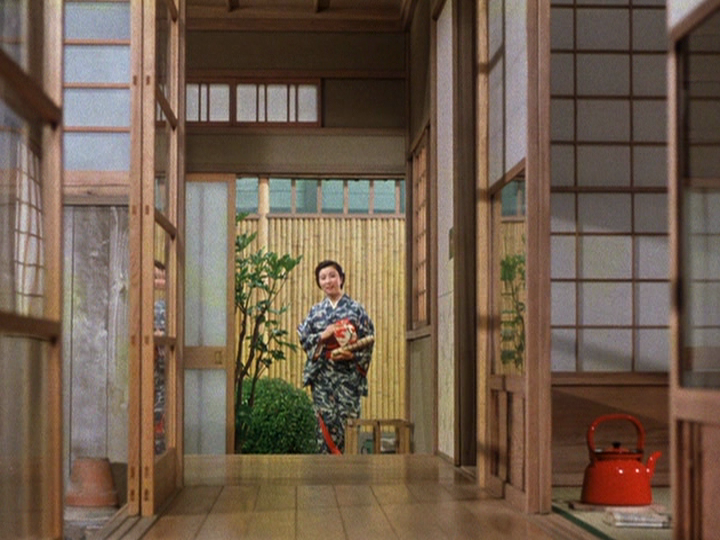

Ozu liked red in particular, evident throughout Equinox Flower: the partially red sign warning of high winds at the train station shown early in the film; the red carpet guiding our eyes into the frame in the first shot at Fumiko’s wedding; the bright red teapot that we see in the Hirayama family home throughout the film; and so forth. Red, and the other colors unspooling throughout the film, tease our eye to observe, rather than assign fixed meaning to, the everyday worlds depicted in Ozu’s images.

I’d argue Ozu’s use of color is not totally abstract, though. His playfulness opens up spaces where connections between color, narrative, and character can be made. Such an approach to color appears again in Ozu’s fourth color feature, Late Autumn, the third film in this month’s Trylon series. In Late Autumn, Ozu regular Setsuko Hara plays Akiko Miwa, a widow whose daughter, Ayako (Yoko Tsukasa), is of traditional marrying age. Ayako initially resists the pressure to marry Goto (Keiji Sada), an employee of family friend Mamiya (Shin Saburi) who is seen by the latter as a good choice for husband. Rhyming a stylized use of color with Ayako’s own resistance to a future determined by others, Ozu again compels the viewer to enjoy the perceptual pleasures of color. Ozu’s style parallels his own close attention to screen characters, especially female protagonists, who often find themselves in a tug of war between traditional expectations and other, potentially more expansive possibilities.

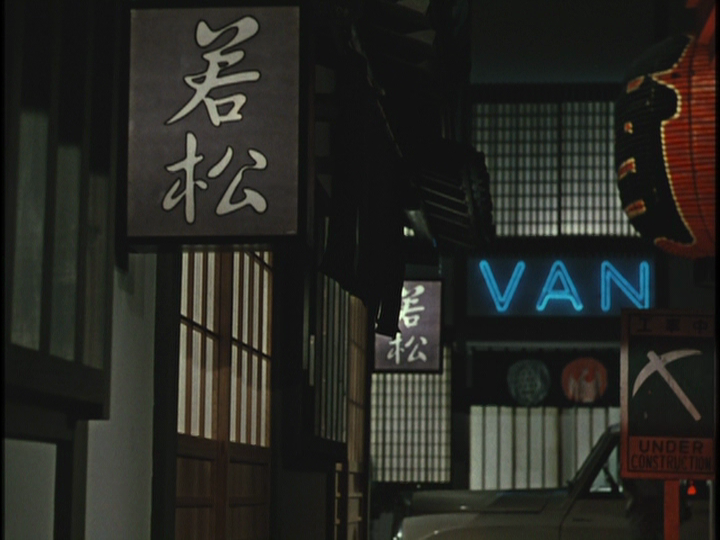

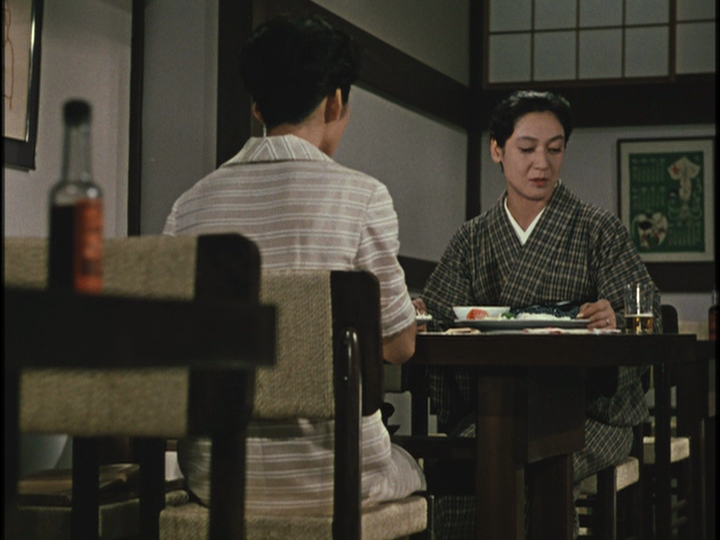

In the first half of the film, Akiko and Ayako meet for a meal. Ozu begins the sequence with a colorful shot outside the restaurant, where we see a blue sign, various shades of red and black, and a bit of the beige and browns familiar from the director’s domestic scenes. The conversation between the characters inside, circling initially around Ayako’s possible marriage, remains light and funny. The two of them banter about how good the meal is and how they shouldn’t waste a drop of beer. Akiko, after finishing her beer (there’s less of it left than she thought, suggesting that this pleasurable meal is nearing its end), remarks how they might not have time to enjoy such meals in the future, after Ayako’s marriage. But Ayako remains adamant that she won’t marry, at least not for now. The conversation then turns to a non-traditional wedding shower of a friend that Ayako will soon attend. The marriage will take place during a hiking trip rather than in a traditional ceremony. Akiko jokes that she should be careful not to fall off a cliff.

Ozu views the relationship between color and meaning in a similar way. He wants us to enjoy the adventure of colorful pictorial perception without falling off a cliff into supposedly “deep” interpretive meaning. This doesn’t mean Ozu’s films are meaningless. It’s just that Ozu doesn’t demand that perceptions of color, or anything in his films, be tethered to abstract concepts or predetermined expectations (the “Ozuesque” Hasumi warned us about). Looking at colorful teapots, glasses, signs, and other everyday objects can be as much fun for us as the beer Akiko enjoys is for her. A red teapot may be, in the end, nothing more—or less—than a red teapot. Ozu’s love of artfully narrating everyday life radiates in these late color films. His depiction of everyday lives, established in his earlier work, only deepens—not in terms of meaning, but in terms of pleasure—as he finds new ways to invite the viewer’s eye to observe his characters and their worlds.

Works Cited

Hasumi, Shiguéhiko. Directed by Yasujirō Ozu. Trans. Ryan Cook. Oakland, California: University of

California Press, 2024. Originally published in Japanese in 1983.

Yoshida, Kiju. Ozu’s Anti-Cinema. Translated by Daisuke Miyao and Kyoko Hirano. Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies at the University of Michigan, 2003.

Frame grabs are from the following DVDs: Ozu, Yasujirō. Equinox Flower and Late Autumn, from Late Ozu, Criterion Collection Eclipse Series DVD boxset, released 2007.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon