| Patrick Clifford |

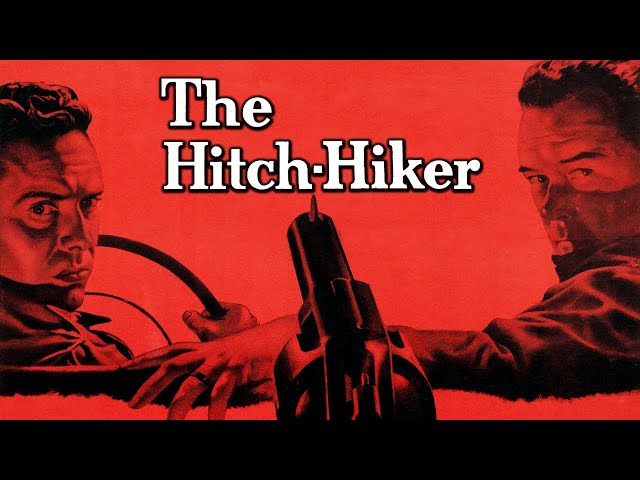

Image sourced from YouTube.com

The Hitch-Hiker plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, December 1st, through Tuesday, December 3rd. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

THIS IS THE TRUE STORY OF A MAN AND A GUN AND A CAR.

THE GUN BELONGED TO THE MAN.

THE CAR MIGHT HAVE BEEN YOURS OR THAT YOUNG COUPLE’S ACROSS THE AISLE.

WHAT YOU WILL SEE IN THE NEXT SEVENTY MINUTES COULD HAVE HAPPENED TO YOU.

FOR THE FACTS ARE ACTUAL.

This is our introduction to The Hitch-Hiker. The first screen. It says a lot.

Originally, Ida Lupino wanted The Hitch-Hiker to be a documentary about Billy Cook, a 23-year-old recently convicted murderer and kidnapper on death row in San Quentin State Penitentiary. She was simply ahead of her time. In 1952, Hollywood had not yet imagined how voraciously American audiences would devour true crime or the perverse satisfaction we would take from realizing that any of it, all of it, “could happen to you.”

Ida Lupino was ahead of her time in other ways too. In 1948, Lupino and her husband Collier Young founded The Filmakers, a production company dedicated to creating films centered around controversial, socially conscious issues and themes. The production company’s first film, Unwanted, tells the story of a woman who has a child out of wedlock. Like The Hitch-Hiker, Unwanted starts with a profound, factual introduction: THIS IS A STORY TOLD ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND TIMES EACH YEAR. Lupino co-wrote and directed (uncredited) the film, and, for the first time, gave American audiences a gut-wrenchingly emotional perspective on where society was heading and what it was like to play the marginalized role of a woman in all of it.

The critical success of Unwanted made Lupino the second woman to be admitted to The Director’s Guild of America. And in 1950, like most of America, she was amazed and intrigued by a new type of story making its way into society—the story of the cold-blooded murderer, the story of Billy Cook. She wanted to make a documentary about this subject, and, in 1952, found her way into San Quentin to interview Billy Cook. She found him to be cold, scary, and calculating.1 She noted he had “Hard Luck” tattooed on the fingers of his left hand and a deformed right eyelid that would never fully close. The visit affected her profoundly, but the Motion Picture Association wanted nothing to do with it. It would not sanction “pictures dealing with the life of notorious criminals.”

By this time in her career, Lupino was an expert in dealing with being told what she couldn’t do and finding a way to do it anyway. She co-wrote the screenplay for The Hitch-Hiker with Collier Young and Robert L. Joseph based on Billy Cook’s rampant crime spree. As the film’s director, she would turn the film noir genre on its head. As film scholar Richard Koszarski notes, “[she] was able to reduce the male to the same sort of dangerous, irrational force that women represented in most male-directed Hollywood noir.”1 Classic noir often centered on the villainous pursuits of a femme fatale; a woman who uses the powers of beauty, sex appeal, and cunning intelligence to seduce male foils to her will. In The Hitch-Hiker, Ida Lupino examines and exposes how the male villain, a homme fatale, so to speak, requires none of these tools to impose his will. In today’s society, terror can be born from nothing more than a man and a gun and a car.

Before we even get to see the face of the man, Lupino shows us the gun. It’s as if she’s telling us, right off the bat, that a male villain’s power doesn’t require foreplay or seduction or cunning deception. It is brute force, in his hand, pointed directly at us, his victims. It’s a beautifully executed noir sequence by Lupino. After briefly introducing two men, Gilbert and Roy, setting out on a weekend guy trip, they pick up Emmett Myers on a dark, desolate road to Mexicali. We see Gil and Roy through the front windshield of the car, brightly lit as they begin small talk with the stranger in the back seat—a menacing silhouette framed against the night sky through the back window. When Gil turns to offer the stranger a cigarette, Lupino cuts to a close-up of a gun rising out of the darkness and pointing directly at the camera. She then cuts back to a bewildered Gil and Roy and zooms the camera into the dark void of the back seat as Emmett leans forward into the bright light, revealing his face, in close-up, for the first time and delivering his ultimatum for the ride of the movie.

“Do as I tell you.”

This is the root and the extent of Emmett’s desires. He is not seeking revenge. He is not after money, status, or recognition. He only wants control. And, as Ida Lupino reveals, the cruel pleasures a man can command with nothing more than a gun to control the situation and a car to help him escape his reality.

The Hitch-Hiker is a psychological road trip movie. It’s a cat-and-mouse game played between a bully who openly declares his intentions to kill and two victims searching for weak spots in the bully’s armor. In the early stages of the journey, Emmitt holds the upper hand and Ida Lupino does an incredible job of letting the audience feel the fear and intimidation the bully holds. She gives Emmett Myers the same deformed right eye that she witnessed on Billy Cook. In a haunting scene where the men have stopped for the night to camp, Emmett forces Gil and Roy to roll themselves into tightly constricting blankets as he watches over them and warns, “I know what you’re thinking and you haven’t got a chance. You guys are gonna die. That’s all. It’s just a question of when… You make pretty good targets from where I sit, and anyway, you couldn’t tell if I was awake or asleep. I got one bum eye. Won’t stay closed. Pretty good, huh?” The bully is always watching.

As they drive farther into their predicament, Gil and Roy start to see through Emmitt’s fear and intimidation. They see opportunities to steer the trip in a direction that favors them. Emmett cannot speak to the friendly Mexicans they encounter. He does not have a wife and children to long for. He doesn’t have anyone to lean on or anything to hope for. Gil and Roy do. In a noteworthy scene where the men stop at a Mexican grocery store for supplies, an innocent little girl playing with baby dolls attempts to speak to Emmett. Without so much as looking at her, he responds, “Get her away from me.” It is the only female role Ida Lupino gives us in the entirety of The Hitch-Hiker. It says a lot.

Ultimately, Emmett’s ignorance is outwitted by Mexican law enforcement and his delusional authority is found to be no match for the strength of Gil and Roy’s friendship. In the closing scene of his capture at a boat yard, we finally get to see Emmett Myers dispossessed of his gun, stripped naked of his power. Lupino slams this home by giving us a closeup of Emmett’s empty hands, cuffed and pressed into his face as he stares and screams into the void.

It’s not unreasonable or unpleasant to think that Ida Lupino might have enjoyed exposing the thin walls Hollywood uses in its construction of male power. That after decades as a highly successful, highly regarded actress working alongside but always under men, she had learned something about surviving and overcoming. And at the end of the day, a man and a gun and a car are no match for a woman and a pen and a director’s chair. For the facts are actual.

Endnotes

1 Ida Lupino and Mary Ann Anderson, Ida Lupino: Beyond the Camera (BearManor Media, 2011).

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

Ha! Very enjoyable read and nice perspective. I look forward to watching this movie through the lense of the femme fatale being the puppeteer of the story.