| Lucas Hardwick |

American Psycho plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, September 29th through Sunday, December 1st. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information. Happy Holidays!

Spoilers ahead, Doc.

Bugs Bunny may have been a master of disguise but his ability to successfully fool his adversaries with a crappy wig and a cheap dress relied on their inability to pay attention. Countless occasions of Bugs’s survival were predicated on feeble attempts at sex appeal and crude diversion. Bugs may have had an entire theatre wardrobe mysteriously at his disposal, but he had a real talent for paying attention to the fact that no one was paying attention.

Daffy Duck was no slouch, but he was hardly a match for Bugs. The 1951 short “Rabbit Fire” begins with Daffy placing phony rabbit tracks ahead of Elmer Fudd and a loaded shotgun in an attempt to elude Fudd from hunting ducks despite the fact that only seconds before Fudd admits to the audience that he’s “hunting wabbits.” Daffy is not even in danger, making his crackpot cunning less to do with his own survival and instead intended to deter Fudd directly into murdering Bugs.

Poking his head up from his rabbit hole, Bugs narrowly dodges a round of buckshot and astutely switches the survival game to Daffy, convincing Fudd that he’s hunting the wrong game and that it is rather in fact Duck Season. An apoplectic Daffy interrupts, insisting that it’s Rabbit Season, and Bugs and Daffy commence arguing for their respective survival: Bugs calmly declaring Duck Season, Daffy sputtering his case for Rabbit Season.

Oldest Trick in the Book

In a classic move from the Middle School Argument Playbook, Bugs employs the tried-and-true fallacy tactic of repeating Daffy’s argument for Rabbit Season back to him, tricking him into calling Duck Season. Fudd, also duped and distracted by Bugs’s slightly less than clever subterfuge, at last pulls the trigger on Daffy, blasting the incensed duck square in the face. Bugs wholly cashes in on NO ONE PAYING ATTENTION!

This level of dopey deception is only amplified throughout the short culminating in Bugs poorly disguising himself as a duck and eventually as a female hunter, fooling Fudd into shooting Daffy in the face about a half-dozen more times. Dressed in hunting chic drag, Bugs even plants a kiss on Fudd’s cheek and it’s not until one of Bugs’s ears escapes the bargain basement wig atop his head that Fudd becomes wise to Bugs’s otherwise foolproof, though slipshod ensemble.

This entire short is all but repeated nearly verbatim in the 1952 feature “Rabbit Seasoning,” but the ineffectual propensity of Bugs’s foils is only made more prevalent by Daffy exclaiming to the audience, after placing about a hundred “Rabbit Season” signs, that it’s actually Duck Season. Fudd is ostensibly hunting ducks until he discovers Daffy’s trail of Rabbit Season signs. Daffy relies on Fudd not necessarily not paying attention, but rather paying attention to the wrong information. Either way, a lack of awareness is necessary for Daffy’s plan to be successful. From there, Bugs coolly exploits Daffy’s and Fudd’s varying degrees of negligence much in the same ways as in “Rabbit Fire,” eventually resulting in Daffy and Fudd’s mutual destruction, and securing his own carefree existence.

Bugs Bunny persists on the inadequacy of his rivals’ comprehension to detail. His tricks aren’t that smart, but neither are his foes. Bugs only needs to employ flimsy tactics against his enemies. He’s not the smartest guy in the room, but he doesn’t need to be when everyone else is so empirically stupid and inattentive. In these instances, Bugs is a direct response to the world around him, demanding that the audience become complicit in his rejection of rules, principles, and often, fundamental moral values And it’s only in this realm of heedlessness and Looney Tunes logic that a psychopath like Patrick Bateman is systemically situated for success as a serial killer hiding in plain sight.

Abandon All Hope Ye Who Enter Here

In Mary Harron’s 2000 film adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s novel American Psycho, Patrick Bateman’s (Christian Bale) world of honey almond body scrubs, herb mint facial masks, Oliver Peoples glasses, Valentino suits, charcoal arugula, squid ravioli, and Silian Rail typefaces exudes a decadence that exists somewhere above the Kármán Line. Luckily for Patrick, everyone in his world has their head so far up their ass they can’t tell the difference between a Paul Allen and a Marcus Halberstram. It’s this world of incessant names, mistaken identities, vapid conversations, and restaurants with indeterminate, highfalutin monikers like Dorsia, Barcadia, and Espace, where no one shuts up and, most importantly, where no one is paying attention.

“This is a chick’s restaurant.”

The film begins in distraction, fooling the audience into believing that a cranberry drizzle is perhaps a gory crime scene and the confectionary syrup is blood spatter. Maybe this tells us more about ourselves than we’d like to know, or rather it assumes to know that we know we’re watching a movie about a serial killer. At any rate, this overthought level of switcheroo brain-fuckery comes full circle in a big way by the end of the film.

Right off the bat, we’re hit with a litany of obscure menu items that sound so aberrant, yet so grounded, it’s difficult to know how real they are. The food on the plates seen in close-up is amorphous and alien. The restaurant is decorated in billowy wall-hangings saturated in pukey mauves and feels like the lobby of a funeral home. One of Patrick’s acquaintances in attendance calls it a “chick’s restaurant” and complains there’s no good bathroom to do coke in. Patrick and his three Wall Street colleagues are definitely out of place, dripping with toxic masculinity and crude anti-Semitism. Harron establishes a volley of diversion and asymmetry in a grab-bag of implausible eloquence. What is even real here? The severity of this question is only compounded as the film progresses.

The lack of attention to detail amongst Patrick and his friends is mockingly in opposition to the distinct detail of their world. Though everyone is specifically put-together, tucked neatly into designer clothes, scrubbed with elaborate skincare regimens, rarely does anyone get a name or fact straight in conversation, and often, when not tediously deliberating on where to eat, these men are discussing who they thought they saw and where they saw them and are never really sure about any of it.

The inconsistencies seem fairly pedestrian at first; someone thinks they spot a Reed Robinson across the room, or is it Paul Allen? Or is Paul Allen on the other side of the room? Who’s he with? Harron’s camera doesn’t even single out anyone in particular, but rather frames up a bland scope of some random group of people at another bunch of tables. Josh Lucas’s Craig McDermott unapologetically mistakes a dreidel for a menorah after making a crack about Allen’s handling of the Fisher account in relation to his alleged Jewish heritage. None of these details are as important as the fact that these details are so meticulously discussed and disputed.

Things only really start to get weird later when Patrick tries to use drink tickets at a nightclub and is scolded by the bartender who reminds him that it’s a cash bar. But the scene only becomes unsettling when as the bartender prepares Patrick’s drink, he says to her, “You’re a fucking ugly bitch. I want to stab you to death and play around with your blood.” And as if that isn’t weird enough, the bartender carries on as though she never hears him. Her disregard of Patrick’s comment is so absurd, it’s almost as if his comment didn’t even happen. And it’s this level of lapse that is intensified throughout that fuels the bloodthirsty, existential turmoil within Patrick.

These instances of dumbfounding disregard are extrapolated in the movie’s episodic progression. Every scene showcases some ridiculous lack of attention. Patrick’s secretary Jean (Chloë Sevigny) asks him to repeat himself when he tells her not to wear the outfit she’s wearing; obvious sexual affairs unfolding and ignored before the eyes of significant others; bloody sheets allegedly stained by cran-apple juice; the trail of blood oozing out of the Jean Paul Gaultier bag stuffed with Paul Allen’s body as Patrick drags it through the lobby of his building; the confusion of “murders and executions” with “mergers and acquisitions.”

Often, when Patrick is socially backed into a corner, he escapes with a flimsy, “I have to return some videotapes” excuse; an odd but presumable pardon that everyone seems fine with. The list goes on and on but in an organic way that even the audience easily chalks up to casual misspeak or misunderstanding. Did we just hear what we thought we heard? Did they just hear what we thought we heard? We become complicit in ignoring Patrick Bateman by accepting that those around him so easily disregard his peculiarities.

Not a fan of The Cosby Show, apparently.

Patrick is confronted about Paul Allen’s disappearance by private detective Donald Kimball (Willem Dafoe). Kimball is ostensibly the most capable and relatable character in the film, and after some pretty solid questioning and a bit of cross-examination, we get the sense that if anyone is going to find out Patrick Bateman’s nightly bloodlust, it’ll be this guy. But when Patrick shoos Kimball out, stating that he’s having lunch with Cliff Huxtable at the Four Seasons, Kimball totally misses the fictional name drop and gloms onto the discrepancy in the location of the Four Seasons in relation to Patrick’s office, and then buys into Patrick’s blatant lie of there being another Four Seasons in closer proximity! Nearly 38 million people watched The Cosby Show every week in 1988, the year this film takes place, and Kimball glosses over the name Cliff Huxtable?

Even the single-most authoritative barrier between Patrick’s crimes and the realm of justice is not paying attention. Or, like Elmer Fudd hunting rabbits during Duck Season, Kimball is paying attention to the wrong details.

Something Called Silian Rail

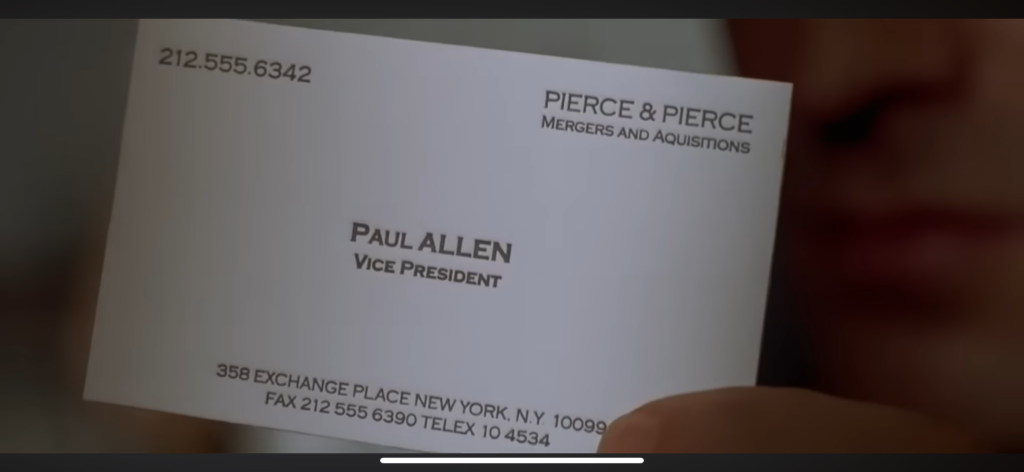

The film’s defining moment of attention deficit is disguised as a quintessence of detail when Patrick and his colleagues compare their recent business card upgrades. Paul Allen (Jared Leto) enters and mistakes Patrick for Marcus Halberstram. Patrick reveals this error in voice-over and diabolically makes no attempt to correct Allen. His internal monologue instead divulges the meticulous similarities amongst the men that has led to Allen’s inaccuracy. These men are all styled in the exact same fashion. When you’re only checking out the Oliver People’s glasses and the Valentino suits and the tans and the slick haircuts, sure, everyone is gonna look like Marcus Halberstram. Patrick, with his astute reserve, is paying attention to the fact that no one is paying attention!

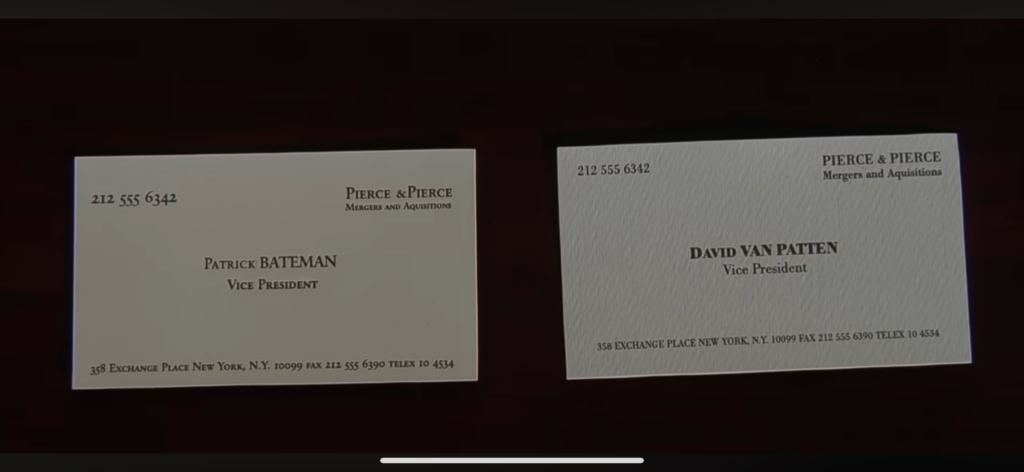

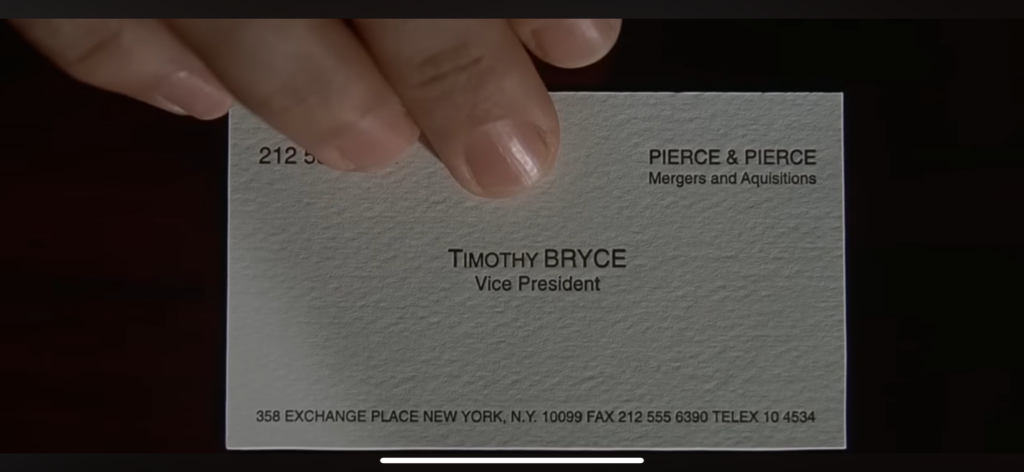

In what amounts to a metrosexual, designer-grade version of a dick measuring contest set in the back pages of a JCPenney catalog, Allen kicks off an existential crisis amongst his colleagues when he shares his business card with Timothy Bryce (Justin Theroux) which prompts Patrick to unveil his new card, smugly bragging that the coloring is “bone” and “the lettering is something called Silian Rail.” Patrick’s pride begins to wilt when David Van Patten (Bill Sage) flaunts his card boasting “eggshell with Romalian type.” Keen to up the ante, Timothy Bryce whips out his “raised lettering, Pale Nimbus, white” bringing Patrick to the brink of physical illness.

From the menswear section of the JCPenney Fall Collection.

Sweating and on the verge of tears, Patrick asks to see the card Paul Allen handed to Bryce moments before. Everyone in the room nervously withdraws as Bryce scrupulously produces the card, Director Harron revealing it with dramatic flair. “That subtle off-white coloring. The tasteful thickness of it. Oh, my God, it even has a watermark,” Patrick’s internal voice in a state of sheer panic. Allen’s card is a sliver of perfection.

But is it? Are any of them?

Let’s look a little deeper, shall we.

First of all, Patrick’s card has a glaring kerning error. There is no space between the “&” and the second “Pierce” on the corporate name in the top right corner of the card. Additionally, the entire template is justified too low and slightly too far left.

Silian Rail and Romalian Type

David Van Patten’s card corrects the kerning error in “Pierce & Pierce,” however, the text sits just a little too high and is justified slightly too far right.

Meanwhile, the type on Timothy Bryce’s card is centered left to right, but it still sits a little low. And though he claims the lettering is raised, it most certainly is not. And what’s his “Pale Nimbus, white” even refer to? The font is clearly a version of Helvetica. “Pale Nimbus” suggests the color, but obviously so does “white.”

Raised lettering. Pale nimbus. White.

Patrick can barely hold his fudge over Paul Allen’s card, and while it is indeed the most refined of the bunch—visually balanced and characterized by the same Copperplate Gothic font used in the film’s opening credits (not an accident)—it does not have a watermark.

No watermark!

Neither Patrick’s nor Van Patten’s fonts are what they say they are. Van Patten’s “Romalian Type” is actually Bodoni and “Silian Rail” is entirely made up. The font on Patrick’s card is Garamond Classico SC. And while we’re at it, the job title on everyone’s card reads “Vice President” and “Acquisitions,” and is misspelled on every account—even Paul Allen’s—as “Aquisitions.”

Can you hear me in the back? No one is paying attention!

Patrick’s card is arguably the most flawed of the group. Between the offset justification and that damn kerning error, it’s downright hideous by comparison. However, if we examine the “Silian Rail” discrepancy, we get a peek into the deeper mind-job of this scene that speaks volumes about the film at large.

Let’s say you’re a movie director with hundreds of capable and talented people at your disposal, and your script calls for a font named “Silian Rail.” And let’s say everything that happens in a film happens for a reason. After about, oh, eight and a half minutes of research you learn there’s no such font as “Silian Rail,” so naturally, you might ask your design team to whip up something you can actually call “Silian Rail.”

Mary Harron doesn’t do this. What does Mary Harron do? Mary Harron does what a psychopath does and lies about it. In a move right out of Patrick Bateman’s playbook, she goes with Garamond Classico SC—hell, she could have picked Futura or Georgia or Bookman Old Style—and tells everyone it’s “something called Silian Rail.” This error works even more brilliantly within the film because for all we know the font really is Garamond Classico SC in the world of the movie and Patrick just made up “Silian Rail” or heard it somewhere else or saw it on the menu at one of his hoity-toity restaurants, and since no one can keep anything straight, he probably really thinks it’s “something called Silian Rail.” It’s worth noting that earlier in the film at Espace, Bryce hands Patrick a menu and says, “The menu’s in braille.” Rhymes a little with “Silian Rail” doesn’t it? And for all we know, Van Patten’s card is actually printed in Bodoni and he’s just as clueless and full of shit as Patrick!

Mary Harron says it doesn’t matter what font any of them are because these guys are pulling stuff out of their ass at an astronomical rate because NO ONE IS PAYING ATTENTION!

This is Not an Exit

By the end of the film, Patrick is feeding stray cats to ATMs and blowing up police cars with a pistol, even to his own surprise. Patrick retreats to his office and leaves a blubbery message to his lawyer confessing to not only the crimes we’ve witnessed, but numerous other atrocities including cannibalism: “I ate some of their brains, and I tried to cook a little.” The scene is intensified by police helicopters and searchlights swarming the area. It’s unnecessarily over the top.

The next day, Patrick confronts his lawyer Harold at one of the many stuffy restaurants everyone hangs out at. Desperate to get these abominations off his chest, Patrick is laughed at and ignored and mistaken for someone named Davis.

Who is Davis? Who is Harold? Is that really a Valentino suit? Are those really Oliver Peoples glasses? Is that really a nice tan? Is that font really Silian Rail? Did Patrick really eat brains? Is that really Marcus Halberstram? Is that really Patrick Bateman?

The final minutes of the film has lead many to suggest that it was all a dream, and these killings are in Patrick’s head, and just like the series finale of Newhart when Dick Loudon wakes up in bed next to Suzanne Pleshette as Bob Hartley from The Bob Newhart Show none of what we just saw ever really happened.

Wrong.

It’s all really happening for Patrick. To deny any of it and tell Patrick it’s all in his head would be like telling a paraplegic to get up and walk.

Listen to Patrick’s voice-over from the end of the movie:

“There are no more barriers to cross. All I have in common with the uncontrollable and the insane, the vicious and the evil, all the mayhem I have caused and my utter indifference toward it I have now surpassed.”

“This confession has meant nothing.”

Patrick’s world has imploded in on itself, accepting the gross inaccuracies that have defined it to this point. His world isn’t paying attention to reality, and in his reality of exploding cars and ATMs with felicidical agendas is the reality where no one knows anyone’s name, restaurants are a bunch of gibberish, sloppy business cards are exalted as an exemplar of status, and where a serial killer, desperate to free himself of his inner turmoil in a society that isn’t listening, is a flawless entity.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon