| Sophie Durbin |

American Psycho plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, September 29th through Sunday, December 1st. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information. Happy Holidays!

“Gloria Steinem… as legend would have it, took [Leonardo DiCaprio] to a baseball game and

said, ‘Please don’t do this movie. You’re the biggest movie star in the world right now, and

teenage girls are living for you, and I really don’t want them all to run to the theater to see a

movie where you’re a man who kills women.’ Ironically she later married Christian Bale’s dad. I always wondered what those Thanksgivings were like.”

— Guinevere Turner on Leonardo DiCaprio’s decision not to play Patrick Bateman in American Psycho 1

This piece isn’t about my shot-for-shot reimagining of what American Psycho starring Leonardo DiCaprio would be, though someone really should write that. No—today, I am more interested in Steinem’s (probably apocryphal) cautioning against DiCaprio’s participation for fear that it would be seen as a kind of endorsement of Bateman’s misogyny. Whether Steinem cared that the film was satire is beside the point. To her, depicting a teenage heartthrob who commits violence against women for profit (DiCaprio would have made $20 million) was an unconscionable use of his star power. DiCaprio did fold, and Mary Harron insisted upon Christian Bale, who until then was known for his child turns in Newsies and Empire of the Sun. Harron favored Bale because he immediately recognized the pitch-black humor of the script, which Harron adapted with Guinevere Turner from Bret Easton Ellis’s novel. The resulting final product is much more interesting than Steinem’s mythical fear: it’s a film that maintains an amused distance from its antihero who becomes more of a clown than a threat. I think an under-discussed secret ingredient to this collaboration is Turner’s hand, which stamps the film with an unexpected undercurrent of lesbian chic.

Some context first! Turner is someone whose name embodies a genre, like “Parker Posey” does for quirky 90s indies. Turner is omnipresent in turn-of-the-millennium lesbian film and television. After her debut in Go Fish, she caught people’s attention with an old-school beauty that hadn’t yet been embodied by a famous openly gay girl. Turner began writing American Psycho with Herron around the same time that The Watermelon Woman was released. Here, she shows up as Cheryl Dunye’s pretty girlfriend from Chicago. She lives in a giant artist loft and lies around all day when she’s not at the video store dissing Sissy Spacek. Turner honed her craft as this type repeatedly in high-profile projects like Chasing Amy and The L Word. The thing that made this lesbian chic chic was a certain nonchalance in how Turner’s attraction to women was taken as a given. She represents a fantasy where existing as a lesbian has become effortless—no secret codes, no yearning in the closet. The lesbians of Go Fish and The Watermelon Woman have already found each other, and their friendships seem organic rather than trauma-bonded coincidences. There’s also a visual language to the genre: nobody wears a bra—both because they don’t want to and because they don’t need to—but everyone is usually unmistakably feminine. Turner is still relevant and busy today, but the work she is most known for is only now coming back into fashion.

I’m not saying that Turner purposefully injected a lesbian perspective into American Psycho’s screenplay. Rather, her involvement carries the baggage of the other films she’d worked on, which blankets the whole feature with her aura. Turner’s take on Bateman is similar to Bret Easton Ellis’s own perception of the character. Commenting Ellis has remarked that as a gay man, he has a on his unique distance from Bateman as a gay man, Ellis shares,: “I think I was watching a lot of this behavior on the sidelines, and I wanted to criticize it.”1 Bale envisioned Bateman as an alien beamed down to New York, trying to figure out how to be cool. Ellis and Turner were both a safe enough distance away from Bateman to write him into something more thought-provoking. In combination with Bale’s complementary perspective on the character, this icy take on Bateman treats him as a science experiment: what happens when you make a man so straight and masculine that he becomes a parody of both?

The film explicitly addresses lesbianism a few times, each with tongue firmly in cheek. Scenario one: Bateman hires two prostitutes and coldly directs them through a passionless series of poses and positions with each other. When he eventually intercedes in the action, he spends most of his time furiously surveilling himself in the mirror. It’s implied that he tortures them after this, and both women are visibly shaken when they depart his apartment. If Bateman intended to play the role of the man so virile that he can introduce two women to the joys of sapphic love and then remind them that the real fun requires a guy, he has failed. Scenario two: Bateman brings his friend Elizabeth over and attempts to instruct her and Christie in another girl-on-girl scenario. In this scene, Elizabeth is played by Turner, who complains, “I’m not a lesbian!” in the in-joke of the century. She and Christie roll around and giggle on the couch a bit. Once again, Bateman attempts to dominate the situation and fails, ultimately resulting in the murder of both women. By casting Turner in this part, Harron sets off the alarm bells of audience members in the know. Turner comes from a universe where lesbianism is the real deal and men need not apply (see: The Watermelon Woman for the best sex scene of the 90s); Bateman has no business in that world. Turner’s archetype is Bateman’s true opposite: in her cinematic universe, the girls come to her, and she always gets what she wants. Bateman has to seek girls out and when he can’t get them to do what he wants, he kills them. Even cast as a silly straight girl, Turner hints at an innate and casual dominance that Bateman can never truly exude.

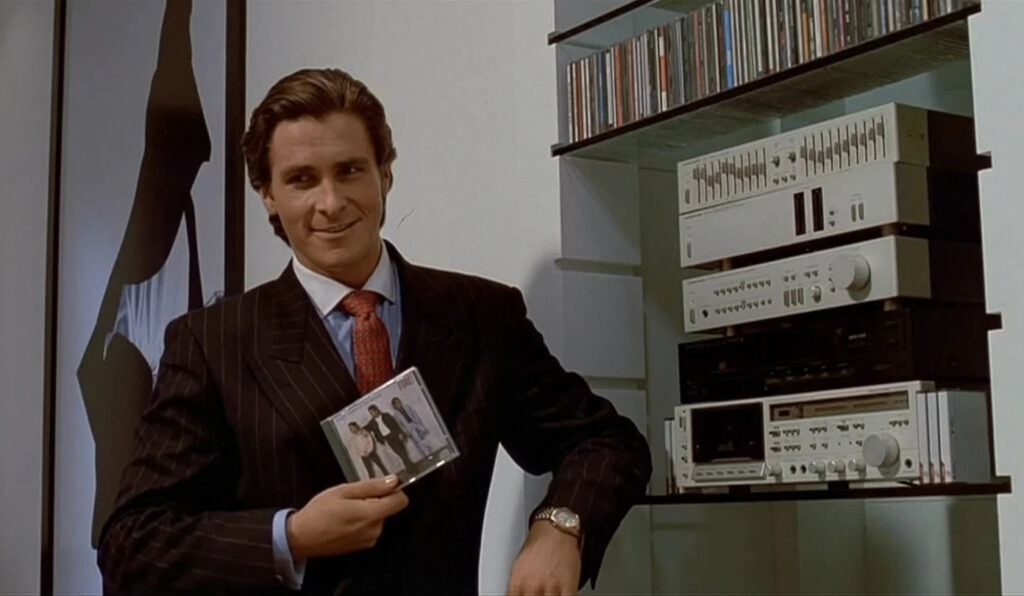

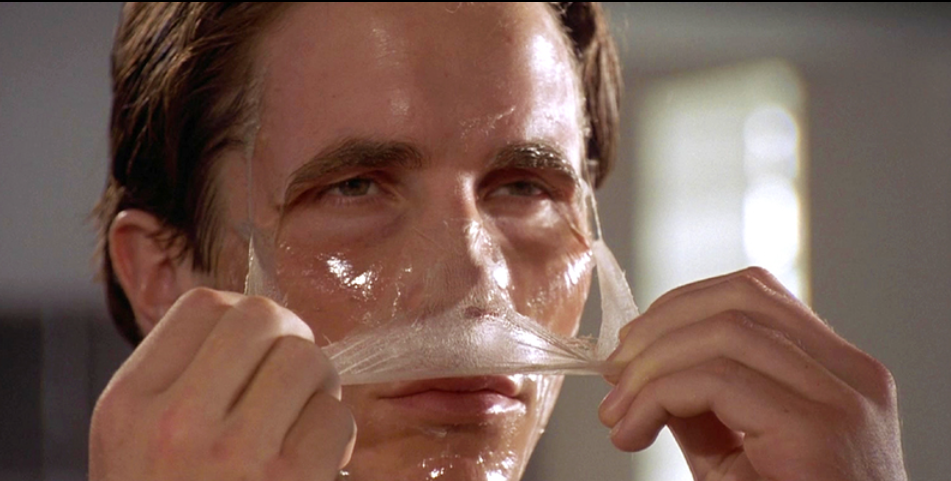

I’ll conclude with a slight tangent. When I was around 16, I rented American Psycho from Blockbuster and proceeded to fall in love with Christian Bale and exercise my usual adolescent inability to understand even the most basic of plot points (here, that Patrick Bateman was actually just a 27 year-old boy loser who may or may not have actually been killing people). This time around, I found him almost intolerably uncanny to look at. In Harron and Turner’s hands, he is an experiment in the natural extremes of the human physique. Harron’s camera lingers plenty on the eerily smooth, dewy surface of his skin and his mathematically impossible muscle tone. Is this the “female gaze” at work? I’d say no—our view of Bateman has little to do with visual pleasure. His appearance is comical, not alluring. Since he’s meant to play a nobody who doesn’t quite get it, it’s important for his presence to be a joke. No, a helpful friend would say to Bateman, if he had any friends: We said you could benefit from working out now and then, not living in the gym! And I told you to splash some water and Irish Spring on your face in the morning, not invest in an entire skincare aisle. But Bateman has no such companions, no one to rein him in, no one to show him the ropes around the real thing that an attractive, successful straight man will convey, which coincidentally is the same quality that makes lesbian chic tick: effortlessness.

Footnote

1 Tim Molloy, “American Psycho: An Oral History, 20 Years After Its Divisive Debut.” (MovieMaker, 2024)

https://www.moviemaker.com/american-psycho-anniversary-oral-history-christian-bale-mary-harron-bret-easton-ellis/3/

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon