| Doug Carmoody |

The Passenger plays in glorious 35mm from Sunday, June 23rd, through Tuesday, June 25th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Cinema of Absence

Michaelangelo Antonioni’s L’eclisse (1962) begins with a directorial confession.

In preparation for a grim romantic argument, Vittoria (a young woman played by Monica Vitti) takes a moment to adjust her surroundings. She reaches through an empty picture frame, pulls an overflowing ashtray out of it, then centers a sculpture. This moment has been interpreted by several critics as metacommentary.1 These observers tend to suggest that the character has performed an act of “arrangement”: she “composed a picture, just as the director has framed a film.”2

On such a reading, the artistic purpose of the scene would be self-reflexive, with the onscreen action drawing the audience’s attention to the constructed nature of the film they are watching. But this interpretation fails to account for the specific manner in which Vittoria composes her picture. The most striking object, the ashtray, isn’t rearranged at all—it is removed.

Interpreting the highlighted metacinematic act in the scene as one of removal seems to reveal an attempt, on Antonioni’s part, to confess to a withholding tendency in his cinema.

In dissecting L’avventura (1960), the late David Bordwell referred to Antonioni’s withholding manner as “restraint.”3 For Bordwell, L’avventura is the culmination of a decades-long drive by Antonioni to develop formal strategies—shooting characters from afar, arranging shots in such a way that faces are not visible—that “block” the audience’s perception of his characters. Removing this information allows Antonioni to engage the viewer on a “subtler level” than Classical Hollywood.

Yet this subtlety would not last forever. By the 1970s, Antonioni found himself venturing into unfamiliar territory, one with a far more flashy, thematically direct mode of image making.

Antonioni’s New Style

Antonioni’s restraint fades as he, like several filmmakers of his generation, undertakes shifts in both form and subject matter between the early and late years of the 1960s. The austere, colorless compositions in his informal modernist trilogy (L’avventura, La notte, L’eclisse) give way to the jarringly colorful palettes of Red Desert (1964) and Blow-Up (1966). Even the spatial logic of the trilogy, epitomized by the overwhelmingly empty islands and vast bourgeois hangouts of L’avventura, seems to contract into Blow-Up’s comically cluttered photography studio.

I will leave to scholars the task of locating the exact moment of aesthetic divergence—for our purposes we can be certain that once Zabriskie Point (1970) arrives, we have reached the opposite side of the canyon from L’eclisse. Zabriskie Point lacks most of the restrained formal qualities of Antonioni’s earlier era, swapping out moody, composition-driven cinema for an obnoxious version of kineticism; the movie somehow ends in both an explosion and a music video.

Antonioni’s new formal era coincides with a more explicit political interest. Where the bourgeois characters in his earlier films stumble across contemporary (or working class) settings on their way between penthouses and decadent parties, the leads in Red Desert and Blow-Up are immersed in them from the outset; Monica Vitti placed immediately into an industrial hellscape in the former, opposite a band of striking workers. The political energy permeates the plot of his subsequent films: Zabriskie Point features a character navigating the student movement (poorly) and practicing an idiosyncratic form of radical politics.

Crucially, Antonioni does not approach political material with much ideological rigor—he maintains his characteristically ambivalent tone towards his radical characters, but fixates on them nonetheless. He adopts a similar fascination with the politics of the late 60s and early 70s, but never fully adopts Godardian political commitments. His ideological ambivalence caused him trouble when his 1972 television documentary Chung Kuo, Cina, landed him in hot water with both the Communist Party and a generation of Chinese schoolchildren.4

Placing The Passenger

It is at the apotheosis of this flight—away from restraint, towards an overt grappling with contemporary politics—that The Passenger emerges. Like Blow-Up, the movie has enough generic thriller trappings that you could almost re-engineer it as a Hitchcockian thriller. Even the plot summary could be Classic Hollywood: Jack Nicholson’s David Locke is a foreign correspondent who, in the midst of reporting on a civil war in Chad, finds himself confused with David Roberston, a dead man who was running guns to the Chadian rebels. Locke doesn’t much mind the confusion, and assumes Robertson’s identity, putting him on the run from European police, Chadian spies, and his own wife.

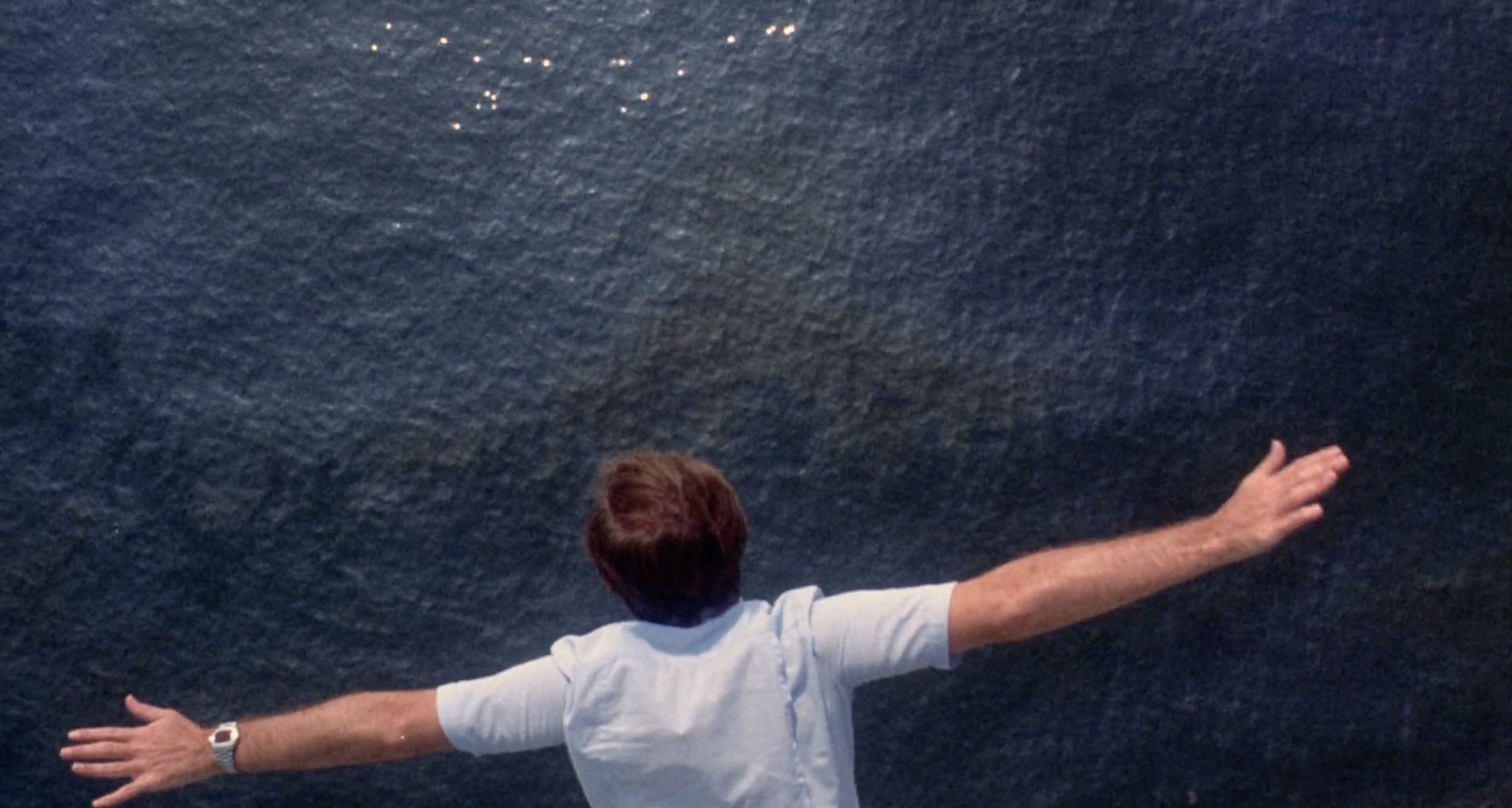

The Passenger supplements this material with a more punctuated formal approach. Antonioni finds himself directing several near-traditional subterfuge sequences followed by a proper car chase. In addition to traditional genre setups, the film deploys an array of conspicuous art cinema maneuvers. There are two shots of upper bodies dislocated into an abstract space that prefigure the showiness of films like The Master. Antonioni also breaks the chronology and visual consistency of the film, interspersing the narrative with subjective flashbacks and an array of footage from the protagonist’s documentary, some of which is reportedly taken from an actual execution.5 There is even a bravura long take.

In other words, the style of The Passenger stands as far from L’avventura as Antonioni’s narrative films will ever get. But his cinema poses questions beyond image making—it is worth asking whether these aesthetic interventions have allowed Antonioni to articulate a new sort of meaning.

“It’s All The Same in The End”

The question of newness lies at the core of The Passenger, posed in the argument between Locke (the protagonist) and Robertson (the doomed doppelganger). The script here features exceedingly direct dialogue concerning the outlook of each character, pointedly contrasting their different brands of cynicism. Robertson derides the world: “airports, taxi, hotel. It’s all the same in the end.” Locke instead sees an existential conundrum: “it’s us who remain the same. We translate every experience, every situation through the same old codes.” Locke’s sense of malaise even harms his ability to connect with his journalistic subjects: “the way we treat them, it’s mistaken. I mean, how do you get their confidence?”

While neither of these philosophies strike me as particularly rosy, the rest of the film paints Robertson as an idealist who actually identified with the locals. According to a spy associate, he “believed in [their] cause.” The conversation reveals that Robinson has been running guns not for money, but out of a proper ideological commitment. Not only does he have the locals’ confidence, but they have his – in an apparently successful strategic partnership.

The juxtaposition between Locke’s ineffective journalistic exchanges and Robertson’s highly effective material exchanges implies that the former’s existential cynicism is a more profound ailment than the latter’s world weariness. Changing the world isn’t easy, but escaping yourself is downright impossible.

The Passenger positions this conflict along metacinematic lines. Robertson explains Locke’s inability to connect with his subjects: “you work with words, images, fragile things. I come with merchandise, concrete things. They understand me straightaway.” This soft jab marks Locke as an Antonioni-esque figure, one whose aesthetic sensibility and detached political orientation leave him alienated from his material and nigh impossibly jaded.

Luckily for Locke and Antonioni, plotwise kismet soon offers a window out of their predicament. Robertson’s death affords Locke a chance to escape his “old codes” and try to forge ahead into something new. Moreover, the specific circumstance forces Locke to cosplay as an idealist. Maria Schnieder, playing the character of “Girl,” bullies Locke into assuming not just the dead man’s identity, but his agenda as well. “Robertson made these appointments. He believed in something.”

The End

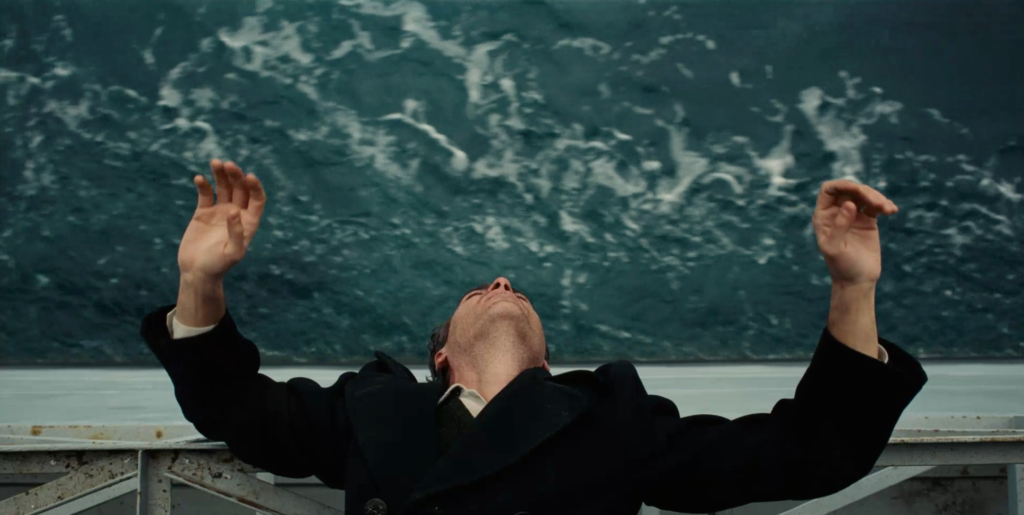

It is fitting that Locke’s quest to find a new self should end with Antonioni operating at the outer limits of his own stylistic repertoire. As The Passenger concludes, we find our formerly austere mood poet constructing a showy, technically muscular, seven-minute long take.

To read more about the scene’s muscularity, check out the ASC’s piece on the “epic shot.”6 The essay is roughly what you’d expect from a society of American cinematographers—it examines the complexities of the technological setup and camera work in gory detail, and even spares a paragraph dissecting thematic significance (Antonioni wanted to have a shot in the film that transitioned from “subjectivity to objectivity”).

But what’s most interesting about the essay is how sparsely it mentions any action besides that of the camera. There’s about a sentence set aside to such description: “As he naps, an assassin arrives to end his life as his unnamed girlfriend (Maria Schneider), his wife Rachel (Jenny Runacre) and the police converge.” And even this meager explainer seems to overstate the cinematic character of the onscreen action. Wife, girlfriend, and police never really converge, but rather stumble across the frame at around the same time. The action taken on camera is confused and languid, with the visual space mostly occupied by window bars and sand.

If what’s in the camera is so plainly uncinematic, what makes the shot interesting? As ever with Antonioni, the answer lies in what has been removed from the frame. Specifically, what this shot was painstakingly constructed to avoid showing is the death of the main character; we see Locke sleeping, we (probably) see his assassin in the courtyard, we see sand, we see him dead, we see him mourned. And somewhere in the sand, the camera ends up on the opposite side of the barred window from our protagonist, so even those last two images come to us in obstructed form.

Through a long take, a technique typically associated with cinematic spectacle and exhibition, Antonioni instead performs a sublime act of withholding—taking pains to block the audience from witnessing, let alone empathizing with, David Locke’s final moments. Locke sacrifices himself for another man’s cause, but it is unclear to the last frame whether his suicide was born of conviction or ennui. The shot is completely different from those emphasized in Bordwell’s examples of cinematic restraint; but the effect is much the same. The film places its central character at a distance, shrouded in ambiguity.

At the end of The Passenger’s unrestrained, attention-grabbing slights of hand, Antonioni returns to himself, weaving a tapestry that, however intricate or striking it may be, nonetheless is most notable for the gaping hole in its center.

Footnotes

1 Richard Read, “The Emotional Historiography of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Eclisse,” Screening the Past, December 2016. http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-41-dossier/the-emotional-historiography-of-michelangelo-antonionis-leclisse/; “Existential Zombies: Antonioni’s L’ECLISSE.” Criterion Channel, 2019. https://www.criterionchannel.com/videos/existential-zombies-antonioni-s-l-eclisse.

2 See Read.

3 “Observations on Film Art: The Restraint of L’AVVENTURA.” Criterion Channel, 2017. https://www.criterionchannel.com/videos/the-restraint-of-l-avventura (shortened version:

4 Alice Xiang, “Senses of Cinema,” Senses of Cinema (July 27, 2015). http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2013/feature-articles/when-ordinary-seeing-fails-reclaiming-the-art-of-documentary-in-michelangelo-antonionis-1972-china-film-chung-kuo/.

5 Ann Hornaday, “‘The Passenger’: On a ’70s Trip,” The Washington Post (November 24, 2005). https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/2005/11/25/the-passenger-on-a-70s-trip/214448eb-b3cc-44b9-9969-3ad7d2f84553/.

6 David E. Williams, “The Passenger: One Epic Shot,” The American Society of Cinematographers (May 17, 2023). https://theasc.com/articles/the-passenger-one-epic-shot.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon