|Jake Rudegeair|

Breathless plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, February 25th, through Tuesday, February 27th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Ever seen First Knight (1995)? I didn’t think so. It was my first tangle with Gere as the famous Sir Lancelot of legend. I was ten and even then I wasn’t buying it. He’s an invincible swordsman and a treasonous Don Juan? I was put off by the cool-guy affect, anachronistic in a movie about The Knights of the Round Table. And don’t get me started on Pretty Woman. He’s the dour moon to Julia Roberts’ sun and no one can change my mind.

Also, I’m not proud of this, but I’ve always thought he kind of looks like a shark. He has those dark doll eyes and more of a snout than a nose. Not that looking like a shark is bad per se. Just always wondered if he’d make a better villain than a leading man.

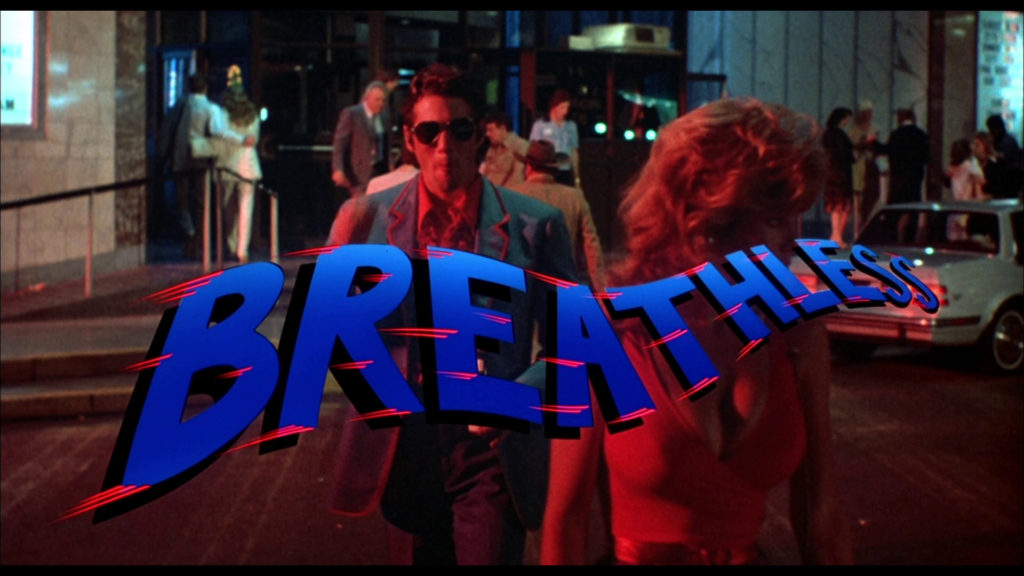

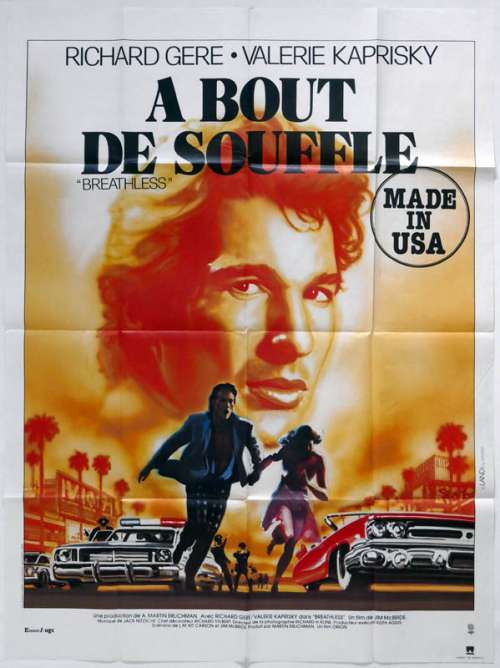

Enter Breathless, Jim McBride and L.M. Kit Carson’s head-scratcher from 1983. Gere plays Jesse Lujack, a dancing, cavalier sociopath. It’s perfect!

But McBride and Carson didn’t write him as a straight-up villain. A grifter, sure. But there’s a sympathy for Lujack and his lost boy psychosis, opining, seeing himself reflected in the polished curves of The Silver Surfer comics he worships. He identifies as the romantic outsider. A detached, superpowered “hero.”

Leave it to 1983 to deliver a film about a handsome, self-obsessed, unstable, hard-boiled bonehead of a protagonist making his horny aimlessness everyone else’s problem.

Valèrie Kaprisky is Gere’s 19-year-old counterpart (absurdly young for this role) as the befuddling Monica Poiccard. You always know exactly what she’s thinking, because it’s either written all over her face or she’s just saying it out loud. With Monica on the mic, you’re always somewhere between an earnest metaphor for love, a ham-fisted cultural reference, or a lilting, prophetic vision of her romantic future. It’s a singular portrait. A deranged woman who can’t quit Lujak no matter how many times he crudely derails her education, jeopardizes her career, breaks into her home, crashes in her bed without asking, or you know, hides a murder.

These deeply weird performances make for something unique and at times, oddly mesmerizing? You’ll never see anything else like it, even the movie it’s remaking.

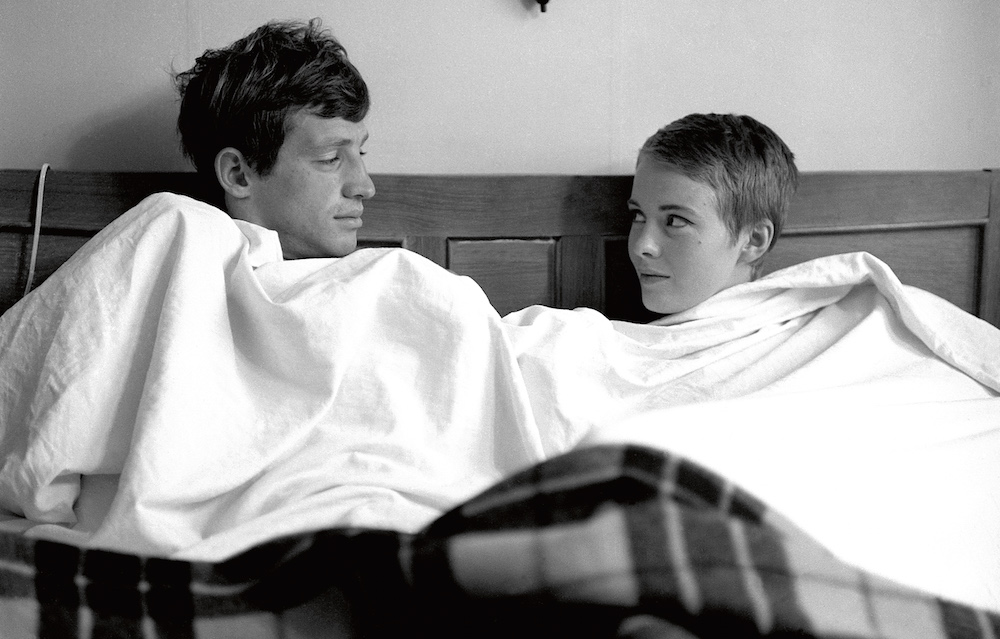

Jean-Luc Godard’s groundbreaking film of the same name was his very first feature in 1960. It helped kick off the French New Wave, and introduced filmmaking moves that have become codified cinematic grammar today. It’s been considered by some to be one of the best films of all time.

So remaking it is… bold.

Vincent Canby from The New York Times nailed it when the remake was released back in ‘83: “…It’s a little like trying to reinvent the light bulb to pay homage to Thomas Alva Edison.” Seems like a bizarre act of hubris to me. But it also feels like McBride and Carson’s version is borne more out of love than egoism. Perhaps in their fanatic devotion to the French master, they were blinded to the pressures and worries that might come with such ambitious shoe-filling? Did McBride and Carson’s lust for movie history get them in over their heads? Or did they know exactly what they were doing?

In Godard’s original, sordid protagonist Michel, Gere’s counterpart, speaks right into the camera while he’s cruising through the French countryside. From the first few moments, you’re an accomplice. Michel is pulling you close. He’s a classically unreliable narrator, obsessed with filmic romance and fantasy.

For all of Gere’s self-serenading back in ‘83, he never reckons with the world on the other side of the camera, save for a few comic-induced reveries. We don’t have access to what’s truly going on in his bobbling head. A story that relied on intimacy and emotional closeness in 1960 becomes a story viewed from a distance in ‘83. Only at the end of each film are the relationships with the audience flipped. In 1960, Michel is distant and faceless at the end—literally running away from the audience he’d shared a bed with minutes ago. In 1983, the ending is the only time Gere seems to reach out to the audience, desperate suddenly, to draw us near.

Was McBride and Carson’s reversal on purpose? Or was the ending a true confluence of character and filmmakers? Was it a union of desperation and humility? A final shrug and some enthusiastic jazz hands? Who could say.

However you look at it, they took a big swing with this one. I wouldn’t say they struck out, though. Gere’s jittery, juvenile performance is an incredible time capsule all its own. If only he had brought this kind of heat to Pretty Woman. It’s fun to see him be so uncomfortably manic, with that fragile smile that shatters at a moment’s notice. He spins and sulks like a child, which makes it even more chaotic when he lashes out in anger. He’s delightfully creepy to watch as he circles Monica like a great white in heat.

The music delivers some high highs. It runs the gamut from Sam Cooke to twangy noir numbers to dreamscapes from Robert Fripp and Brian Eno. The Jerry Lee Lewis worship is a little jarring, but you get used to it.

There’s also no shortage of bizarre sex. It’d be hotter though, if these characters weren’t such goddamn lunatics. But they are very pretty people, it can’t be denied (if you’re into the whole Cartilaginous thing).

This movie has a bizarre style and rhythm all its own. It’s like an outsider trying to rebuild a casino from a distant sketch on a tiny napkin. Like a lone alien surfing the cosmos, or a displaced grifter bouncing through time, a great ball of fire. Breathless is a doomed flash of optimistic passion fated to fade fast.

I have to give it to McBride and Carson, though. They actually lived out the rebellious motto of their own main character. Jesse Lujak, rejecting the unknown, tells us he’s tired of all these questions about the future. “Fuck it, roll the dice,” he says.

And they really did.

Edited by Finn Odum