|Yuval Klein|

Branded to Kill plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, January 28th, through Tuesday, January 30th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

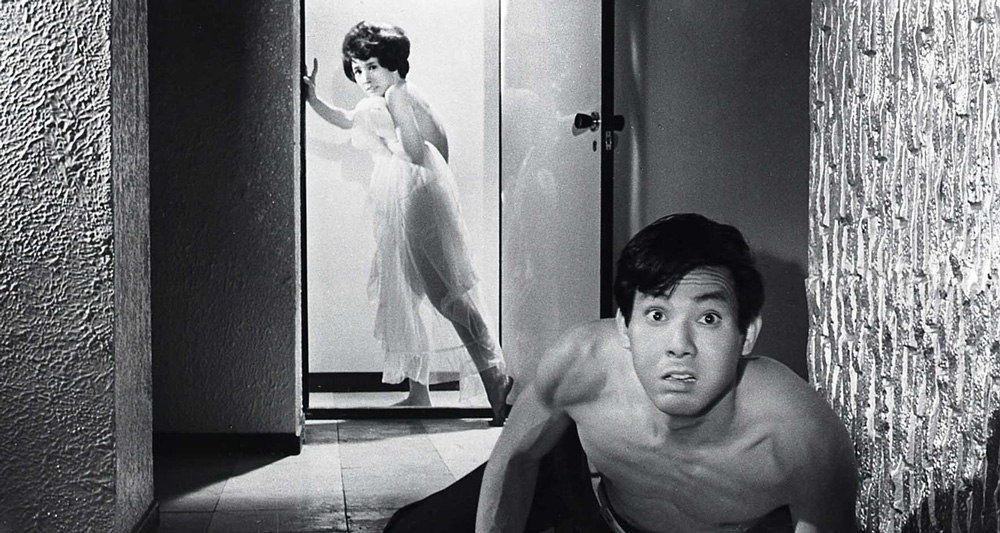

With action, slapstick, deadpan machismo, a jazzy soundtrack, and avant-garde edits, the tone of Branded to Kill is set in an extensive and superbly shot shootout scene, in which our protagonist, a “highly ranked” assassin named Gorô, is ambushed. With him, an anxious and formerly ranked acquaintance who is heavily intoxicated when the shooting starts, dead when it ends. The violence is followed by eroticism, comedy, and more violence (a common pattern throughout the film). Scenes are shot artfully and with many images pieced together percussively in ways that subvert ideas of time and space. A montage of his assassinations, which experiments with unique ways of portraying violence on film, plays out energetically. Once again, comic relief is provided as a theatrically appalled worker—in one of the buildings that were host to the bloodbaths—searches for the protagonist in horror as the audience watches Gorô alighting on a floating balloon through the window.

The reception of Branded to Kill was initially devastating. Critics claimed that there was no continuity in emotion, time, and space, that the film was disarray. The head of the Nikkatsu studio didn’t understand the film either, so they refused to release it and only did so after protests by the public and a trial in which the studio was sued for breach of contract. Having always been a rebel who pushed for films that were ahead of the times, this revolt against a studio pushed the contention of director Seijun Suzuki’s reputation too far. Studios wouldn’t let him make movies for the next ten years. He made a living by directing commercials.

Suzuki claimed that neither Branded to Kill nor Tokyo Drifters (his most acclaimed films) are philosophical, rather entertaining and exciting. He characterized the movies as strange but nonetheless commercial films that have been exalted to the status of an art film. However, it is not entirely absurd for critics to contradict him on this point because he himself was not involved in the screenplay of these films. In his hands-on (which includes many alterations to the script) directing, a dazzling and singular energy is infused into the film, though he may not have entirely seen the depth or height to which Branded to Kill reached. When asked about the motif of butterflies, for example, he joked that one of the writers liked butterflies, that’s why they’re so prevalent, and that the writer was the one to ask any further questions about the matter. It’s possible that the butterflies are more inscrutable than an enigma, that they are just decorations, but there are clearly more layers to some of the other details, more multitudes than an entertainment film.

Gorô and his wife are despicable human beings, a match conjured in the gates of hell; their heinousness banally reflects negative gender stereotypes: she is materialistic, unfaithful, and emotionally manipulative, while he’s cold, violent, and unabashedly womanizing in his words and actions. There is the introduction of Misako Chujo, who fills a morbid shoe with butterfly designs (a soon-to-be related reference). She assigns him a risky and difficult task. His scope is set on the target but a butterfly that passes by tampers with the precision, rather killing an unfortunate passerby. Naturally, the climax of this violence is followed by more beastly eccentricities of sex and violence. Throughout the fragmented narrative, his sexual arousal (whether because of women or the smell of rice) is a precursor to frustration and disaster. The moment is far from an exception. His wife shoots him, runs away naked, and sets the apartment on fire.

Wounded, dejected, and macho, he limps to Misako’s apartment. In her living room, butterflies are pinned to the wall and birds are flitting in a little cage (two playfully contrived motifs). Misako is an utterly hollow woman. The attachment that he develops for her is a comical parody of more “down-to-earth” films that portray characters resembling human beings rather than the strange and sordid figures showcased in this film. He is unquestionably a sociopath who doesn’t grieve any of his “objects” of killing, but after narrowly preventing Misako from killing him, he can’t bring himself to kill the hollow woman who lives in a morbid reality of pinned butterflies, birds, and death.

When he returns home, his wife ambushes him with a hug; this is another cynical parody of human beings portrayed by the wife who, like the two purveyors of death, is devoid of any redeemable qualities except for physical attractiveness (which is not exactly a virtue). The kisses that follow mislead us into expecting another erotic scene, but then she is taken aback when she realizes that it is not his boss who has made her acquaintance … Instead, the maniac himself. “It can’t be! This has to be a joke!” she exclaims. In a typical crime thriller, this would be the emotionally climactic moment in which a love interest admits to her betrayal, her eyes leaden with tears. The wife fills the role convincingly. If one were to watch this scene out of context, they would find it to be sincere, but at the end, her scheming, opportunistic eyes peek out through the gaps of her fingers. With a quick cut, their wild and tempestuous cycle begins anew, as she is once again seducing him with feigned tenderness and he is sulking coldly by her. Immediately following this are two deaths: that of his wife and his mistress.

He professes his love to a film projection of Misako who is killed by gangsters. His ascetic adherence to the “assassin’s code” is shattered by binge drinking in various public venues. Only our hero remains now, and he is informed that the mysterious Number One exists, and that Mr. Number One remains number one. The “mysterious Number One” and widely disseminated ranking of the professional assassins is absurd. It is an absurdity that consumes Gorô and reignites his machismo fuel as he ventures outside with gun in hand. He is ambushed once more and another artful shootout comes about as a result. The jazz score returns at the end while he is in ecstasy over his sole metric of accomplishment in life: whether he still breathes and lives to be as high as possible in the assassin rankings. Walking away from the battle scene, he encounters the mythic “Number One”, who warns the protagonist of his imminent death. The new entourage member is cut from the same cold and otherworldly cloth as the other characters.

The love of Gorô’s life, rice, is piled on a plate beside him while he schemes ways of protecting himself from “Number One” by getting to him first . Number One is simply and objectively better than him; he always tracks down his precise location whereas Gorô has been unable to track him since the beginning of the film. Abruptly, Number One holds Gorô at gunpoint. They discuss their upcoming showdown. Number One proves to be similar to Gorô but more refined. He is wholly pragmatic, applying every skill and rule of an assassin in an exacting way, and is not subject to fits and whims, only to unwavering sublimity in missions.

Throughout the film, Gorô is on a mission to conquer the unassailable: to build a loving relationship with a scary and emotionally hollow woman, and to prevail over an assassin who hasn’t the slightest chance of being finessed. He and Number One lay side by side without allowing themselves to close their eyes; meanwhile, Number One begins to snore. Being shaken awake, Number One says “That was a nice nap.” Gorô replies, “You slept? Your eyes were open the whole time!” Number One replies: “Can’t you sleep with your eyes open? Your training must be inadequate.” The comical moment reinforces the theme, one which has been extracted from the disarray. Number One explicitly uses the word “inadequate.” He repeats this word every time Gorô struggles to outmaneuver him. Number One is an infallible clone of the protagonist. The feeling of inadequacy that he provokes in Gorô is a constant source of rage that consumes him completely.

In a memorable closing scene, Gorô kills Number One, but his moment of glory is short-lived as he himself dies and falls out of a brilliantly illuminated boxing ring into darkness, most probably dying too. Metaphorically, the boxing ring, which is normally used to showcase a spectacle of violence to the masses, is the senseless and lonely venue for his life. All of his successes are fleeting victories over death, and on this desolate stage shines a blinding light that gives him delusions of greatness and self-importance. The nonexistent audience does not witness the spectacle of his depravity in the streets nor the ephemeral glory of becoming number one assassin. All of his battles have been fought for the sake of recognition, but what chance did he ever have? “Inadequacy” is the implicit motto of the film, that of a hedonistic young man full of the grandiose, of the violent, of the sensual, but barren nonetheless.

Branded to Kill has since been lauded by critics and watched as a philosophically potent and disturbing film. Having aged into a classic of arthouse cinema, a new generation is giving it the integrity of screenings. The Trylon community will be taking part in this development next week so that we will not make the same mistake of 1960s critics who averted their gaze from the beautiful disarray of Branded to Kill.

Edited by Finn Odum