| Finn Odum |

Holy Mountain plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, December 8th, through Sunday, December 10th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Dazed & Confused: You’ve never been confined to one medium—you’re famous as a comic-writer, filmmaker, playwright…

Alejandro Jodorowsky: I’ve always admired Leonardo Da Vinci or Jean Cocteau, who were the same. Objects aren’t just one thing now. Very soon iPhones will also be sex vibrators, they’ll be useful for masturbation. In the same way, modern artists need to be like modern objects that are polymorphous.

0. The Fool

I’ve always had a thing for weird little freaks.

They’re exactly what they sound like: people whose behavior is absurd or unsettling. They have complicated relationships with subjects like sex, drugs, and religion. They can be repressed or unhinged, unkempt or dressed in a three-piece suit. Think Elliot and Beverly Mantle in Dead Ringers, the plumber from The Plumber, or Sam Neil in half of his filmography. Weird little freaks are boundary-pushing characters that provoke audiences into asking the big questions: What in our culture—whether it’s social conditioning or political conflict—led to this freak’s existence? Why do we perceive this behavior as taboo, and where did that perception come from?

Are you born a weird little freak, or does society make you one?

Many of my favorite filmmakers focus on this kind of artistic discomfort. They are the peak little freaks: creators whose art unsettles the audience with violent imagery, bizarre conclusions, and outrageous characters. Some, like Werner Herzog and Robert Eggers, are subtle little freaks, directing their actors to deliver unhinged performances. Others, like Sam Raimi and Pedro Almodóvar, utilize upsetting subjects to bring terror (and catharsis) to their audiences. Then, there are the top-tier weird little freaks like David Cronenberg, the mind behind Videodrome’s VHS tape vagina and Crash’s violence-induced sex scenes.

No one, however, tops the inaugural member of The Weird Little Freak Director Hall of Fame™. The king of kings. The freaks’ freak. Alejandro Jodorowsky.

The Weird Little Freak Director Hall of Fame™

Top row, left to right: Alejandro Jodorowsky, David Cronenberg, Pedro Almodóvar

Bottom row, left to right: Werner Herzog, Sam Raimi, Robert Eggers

IV. The Emperor

Alejandro Jodorowsky (pronounced ho-do-rov-sky) is a Chilean-Ukrainian director who worked primarily out of Mexico during his filmmaking career. Jodorowsky got his start in the performing arts as a clown, then moved on to become a director, and now writes comic books while dunking on Walt Disney. He’s also a tarot practitioner—like myself—and uses the Tarot of Marseille in his films and comics. That last one doesn’t quite make him a freak. I just think it’s neat.

No, Jodorowsy’s freakish traits come out in the facts I’ve excluded. He is no stranger to the absurd—he relishes in it, having built his career on bizarre statements and production stunts. When promoting his first film El Topo in the US, he dressed up in character and told audiences he ate “human meat tacos with Diego Rivera.” He hated using celebrities in his films because he thought they ruined art. His films contain live animals that he may or may not have stolen from zoos. He is a freak— so much so that his work helped found a filmmaking movement in the sixties.

Major Arcana cards from Jodorowsky’s Tarot deck, How Jodorowksy explained Tarot to his Cat.

The Panic Movement was a short-lived filmmaking style that focused on chaos, violence, and surrealism. On the surface level, Panic films were meant to be so disgusting that they removed surrealist works from the public eye. They pushed vanilla audiences away and attracted only the weirdest of little freaks. But on another level, the boundary-pushing nature of Panic Movement movies forced audiences to confront their perceptions of the world. Though outrageous, confounding, and often a little gross, Panic films were loaded with thought-provoking themes.

There’s no better example than Holy Mountain, Jodorowsky’s magnum opus, which was deemed so uncomfortable that after its premiere at Cannes, producer Allen Klein refused to release it. For thirty years, the only available copies of the film were the ones leaked by Jodorowsky to content pirates. The film accomplished that surface goal of avoiding the mainstream, but the director still desired for his film to be seen; for his weird little freak ideas to be consumed and questioned. But what could be so uncomfortable about Holy Mountain that it needed to be banished to the shadow realm?

XXI. The World.

At a Friendsgiving meal I went to recently, I struggled to pitch Holy Mountain to some of the guests.

Yes, the movie isn’t quite dinner-friendly. In an early scene, a tourist is assaulted by a police officer while her husband laughs and photographs the encounter. Later, a young man is forced to castrate himself in order to join the police. At some point, a bevy of dead birds are marched through town—which provoked an outcry from real-world animal rights activists, despite assurances that the birds came from a restaurant. And the penises! So many penises.

Holy Mountain is vile and violent, but that’s not where my struggle with it came from. It was because I couldn’t articulate how much I loved the layers buried underneath. The outrage is the point, designed to force the audience to confront their biases. In Holy Mountain (and his later psychological horror film Santa Sangre), Jodorowsky calls attention to white American stereotypes of Latin America by exaggerating them. Holy Mountain opens in an unnamed Mexican city, where police murder children while tourists document their misery with Polaroid cameras. A city of lizards dressed in Aztec headdresses gets decimated by an army of conquistador toads for the tourist’s entertainment. Indigenous people lie dead in the streets, while a herd of Catholic sex workers wander around seeking clients or Christ (whichever comes first). It’s an Ouroboros swallowing its tail; it is outrageous because it’s based on stereotypes and it outrages the people who stereotype it.

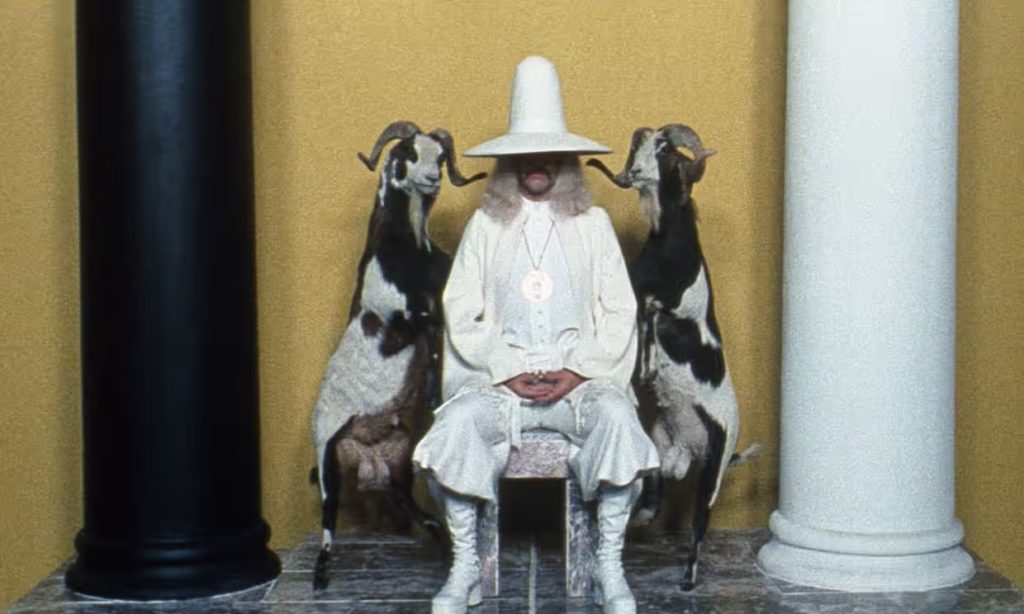

Sex, sexuality, and gender performance are also torn to shreds in Holy Mountain. Almost every character besides the lead challenges gender norms. Women are bald and men have long hair; Jodorowsky himself rocks a braid and painted fingers, while his ex-wife Valerie (Sel, the representation of Saturn) is dressed in a black suit. Mars is represented by a lesbian weapons manufacturer who sleeps with two bald women and wakes up her naked male secretaries every morning. Venus is a man who sells “beauty products” and has (mediocre) sex with his female secretaries. Neptune is the police chief who demands the aforementioned castration. Uranus is a financial adviser in a kinky relationship with a woman who he’s chained to. In the seventies, these characters were on the social outskirts. The mere image of a woman holding a gun with a cross on it would be enough to kill my grandmother.

Holy Mountain’s discomfort holds the potential to provoke self-reflection. If the audience is uncomfortable seeing a masculine woman building weapons or a man submitting to his feminine partner, they have to ask themselves why it upsets them. If they are unsettled by the supposed violence in a country they’ve never even been to, they need to consider who created that imagery in the first place. They need to ask if Jodorowsky is the weird little freak for making the film, or if they’re the weird little freaks for not getting the point.

0. The Fool, Once More with Feeling

An important distinction must be made about the weird little freak: though they might use outrage against the public, they aren’t trying to be weird. They are not edgy for the sake of being edgy, or shocking just to say that they shocked people. If you have to try, you are not succeeding.

Alejandro Jodorowsky didn’t make his films provocative for the sake of only upsetting audiences; he designed his art to embody his ideals, politics, and experience. He drew from his time in the circus and his surrealist counterparts, the serial killer he met on the street, and the relationship between his parents. He looked at his life and turned it into vibrant, visceral videos for the world to see. They just happened to be unhinged.

I love weird little freaks because I like people who see the world for what it is: messy, chaotic, and full of rules that can be broken. I enjoy asking why—even if the answer isn’t satisfying, or if there’s no answer at all. And I’m a sucker for anyone who sits down in an interview and, in the same breath as he mentions DaVinci, claims that smartphones will one day operate as vibrators. And Jodorowsky wasn’t wrong; you can go to Smitten Kitten and get an app-controlled vibrator for as low as $69.95. But why would he say that in the first place? What does that have to do with art? That’s for the weird little freaks to know and for you to find out.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon