| Casey Jarrin |

Apocalypse Now’s opening scene: firebombed napalm jungles fade to Captain Willard’s face (Martin Sheen)

Apocalypse Now plays at the Trylon Cinema from Saturday, November 11th, through Monday, November 14th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Prelude to a Pathology

Every morning in tenth grade, I’d press PLAY on my Panasonic VCR, the opening sequence of Apocalypse Now cued up and ready to explode into orange-red-pink pyrotechnics of helicopter-war-as-cinema-painting, soundtracked by Jim Morrison’s breathy tortured vocal writhings.

I could not watch this scene enough. War sublime, the ultimate lie.

Why was this what made me feel most alive, in those dark teenage years, when 3 am infrared bombings of Baghdad glowed green on the TV, Wolf Blitzer’s voiceover to this Bush-era Blitzkrieg steamrolling into our living rooms?

I suppose I’ve answered my question.

Fight war with pseudo-war.

Make it beautiful and contained.

Tame the real-life beast.

Cage it within an 18” screen.

Apocalypse Now is an indoctrination into ecstatic cinema experience. Through its archive of sounds, photos, spectacle war and spectacle death—presented in a series of extended set pieces, scenes which function as self-contained lessons in the twisted sensorium of war—Coppola’s intoxicating nightmare makes us desire more and leave morality at the door.

Coppola is calculated, deliberate, near-maniacal in his manipulation of our hearts and minds. He wants to enthrall us, to evoke addictive physiological response, his camera a sadistic arm plunging into our chests, squeezing our hearts and rattling our guts around, sparking nerve endings, commanding:

WATCH.

FEEL.

YOU WILL

BE EXHILARATED.

This is War

Apocalypse Now director Francis Ford Coppola at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival.

Photo credit: still from the documentary film Hearts of Darkness (1991), directed by Fax Bahr, George Hickenlooper, and Eleanor Coppola, based on her memoir.

When a rough cut of the film premiered at the Cannes Festival in 1979, full-bearded Coppola notoriously proclaimed that his film wasn’t about war, not a mere approximation of the experience, rather it was the thing itself. Sitting at a long table, speaking into a cavalcade of press microphones, bombarded by the click and flash of press cameras, it’s both thrilling and cringy how seriously Coppola takes himself.

I can’t stop thinking about a mind-blowing article by journalist Lawrence Weschler, “Valkyries over Iraq: The Trouble with War Movies,” about how all anti-war films at their core celebrate the sensory aliveness of war. His conversations with Jarhead author Anthony Swofford and Apocalypse Now editor Walter Murch keep circling back to the same “gnawing” question: “Whether it’s even possible to imagine creating an antiwar film or any depiction of war in film necessarily lends itself to military pornographic exploitation.” Swofford is a hard-liner, insisting Kubrick and Coppola’s war films are “all pro-war, no matter what the supposed message.”

I’m not sure Apocalypse Now is anti-war and I don’t think that was ever its intention.

Whatever You Do, Don’t Shoot the Puppy

Apocalypse Now: American GIs Chef (Frederic Forrest), Lance (Sam Bottoms), and puppy

Once upon a time, when I taught college film seminars on the aesthetics, ethics, and phenomenology of violent cinema experience, Apocalypse Now made a prominent appearance. Again and again, I was struck by which scenes affected students the most.

One sequence troubled them more than any other, evoked tears and screams and the shielding of eyes: the so-called Sampan Massacre scene in which Willard and his crew of GIs search a boat filled with fruits, vegetables, chickens, an entire family—and a wide-eyed puppy.

Why is this the scene that feels hardest to experience?

We spent entire seminars digging into the film’s multiple scenes of hyperviolence: the Flight of the Valkyries aerial obliteration of bridges, a village school, and the lives within; the climax at the Kurtz compound with the brutal yet sublime crosscut between the water buffalo sacrifice (which is real) and Kurtz’s murder; the chaos at Do Long Bridge with its pyrotechnic acid trip explosions. Yet to most students, those sequences felt manufactured, choreographed, deliberately staged by a sadistic auteur and his crew.

Cruelty toward a helpless floppy-eared puppy evoked a different, more immediate physiological recoil than watching the bombing of villages.

Even if every human aboard that boat is murdered by a teenage GI’s machine gun freak-out.

Whatever you do, don’t shoot the puppy.

Violence: A Memoir

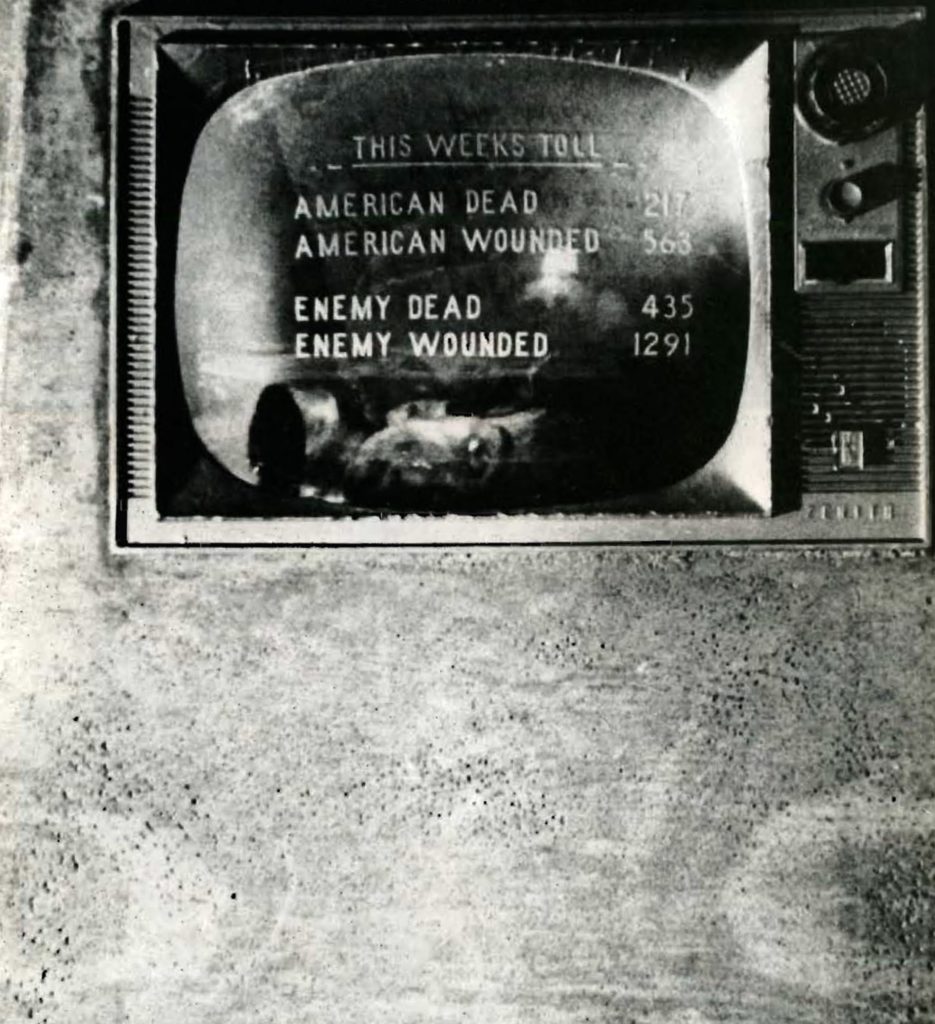

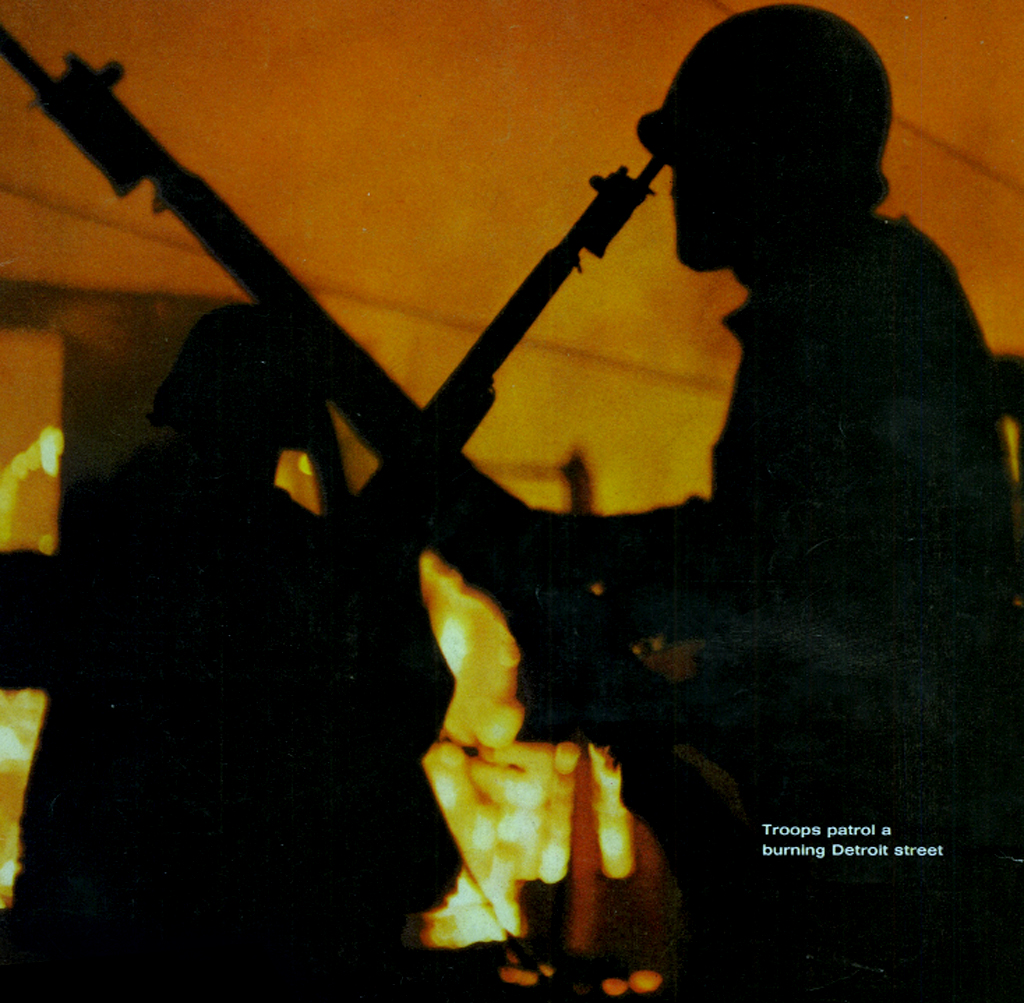

When I think about what violence on screen does to us, all roads lead back to Vivian Sobchack’s “The Violent Dance: A Personal Memoir of Death in the Movies.” This 1974 autobiographical essay on the physiological experience of cinematic violence takes us on tour from silent films to animated classics to full-color blood ballets—from the Buñuel-Dalí collaboration Un Chien Andalou to Disney’s Bambi to Bonnie and Clyde—placing a spotlight on the cultural pivot from abstracted violence (violence which happens quickly and at a distance) to the 1960s full-color bloodbaths of Kent State and MLK, JFK’s brains and tanks rolling through apocalyptic Detroit, scenes of the conflict in Viet Nam flashing on TV screens.

Above: Apocalypse Now‘s Do Long Bridge sequence bears a haunting resemblance to 1967 Detroit fires. Below Right: Detail of front cover of LIFE magazine, August 4, 1967. Below Left: American installation artist Ed Kienholz’s commentary on 1960s network news death tolls and the callous hierarchy of lives

As a trauma survivor who spent way too much time researching cinema violence, embodied empathy, and lived histories of violent conflict before being diagnosed with complex PTSD, sometimes my whole life feels like an attempt to understand what violence does to us. Whether experienced directly in our bodies or viewed on screens, what does violence activate, what does it shut down? What neural pathways does it form, reshape, fry? What does it teach us?

In our world of Instastories and live streams, harrowing police stops and civilian murders, blood is everywhere visible: contained yet uncontainable, repostable yet still utterly incomprehensible.

I’m not sure our exposure to violence on screens teaches us anything.

But it does change how we see.

Ennui and Wartime Gothic: The Scene Everyone Loves to Hate

Colonial Undead: Golden hour on the French plantation in Apocalypse Now (Redux & Final Cut versions)

i.

French plantation scene

shades of cream & lace

no electric fireworks

to steal us away

from this weary

gilded tableaux.

Just the slow crawl:

Colonial Undead

Gothic Occupier

Miss Havisham

taking her tea

then turning

from today’s

undoing

of bodies.

ii.

In The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien confesses that most of “being at war” is “aggressively boring.” Empty time. Interminable waiting.

Maybe that’s what Coppola is up to in this seemingly endless, widely reviled scene: a point of contrast to the pyrotechnics and the bombast.

So we crave the return of fire and noise, evidence of breath and alive.

Apocalypse Now as Wunderkammer

Here are some well-known and little-known facts, casual and sobering observations, unverified assumptions and hunches about Apocalypse Now (in no particular order):

Coppola’s cast and crew barely survived the production.

Martin Sheen punched his fist into that mirror,

refused all efforts to stop the bleeding,

I’m meeting my demons.

To call this improvisation

would attach

too much

volition.

A few weeks later

he’d be airlifted

into Manila

when his

heart

stopped

momentarily.

The Philippines military loaned its helicopters

to the Flight of the Valkyries

aerial bombing sequence.

The bodies scattered about the Kurtz compound

may not have been props

but actual corpses.

I presented a conference paper:

“Photographic Archives

of Death in Apocalypse Now.”

Everyone was disappointed

when they found out

I was a woman.

OMG You’ve never seen Apocalypse Now?: An Invitation and A Warning

addictive

embodied

sensory

alive

watch

feel

look

see

come closer keep your distance

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bahr, Fax, George Hickenlooper, and Eleanor Coppola. Hearts of Darkness. American Zoetrope and Triton Pictures, 1991.

Coppola, Eleanor. Notes on the Making of Apocalypse Now (1979). New York: Limelight Editions, 2001.

Coppola, Francis Ford. Apocalypse Now. 1979.

O’Brien, Tim. The Things They Carried. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

Sobchack, Vivian. “The Violent Dance: A Personal Memoir of Death in the Movies.” Journal of Popular Film 3: Winter 1974. Reprinted in Screening Violence. Ed. Stephen Prince. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000.

Weschler, Lawrence. “Valkyries Over Iraq: The trouble with war movies.” Harper’s Magazine. November 2005.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon