|Natalie Marlin|

The Silence of the Lambs plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, October 27th, through Sunday October 29th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

And I said, “Oh, no, sir

I must say you’re wrong

I must disagree, oh, no, sir

I must say you’re wrong

Won’t you listen to me?”

Hearing it solely on its own terms, “Goodbye Horses” is an achingly beautiful song. Q Lazzarus’s voice quavers but never loses its assuredness. She makes the most of her low resonance, embracing her voice’s androgynous qualities. William Garvey’s gorgeously cryptic lyricism is just as crucial to the song’s mystique: take, for instance, the elliptical second verse—“He told me, ‘I’ve seen it all before / I’ve been there, I’ve seen my hopes and dreams a-lying on the ground / I’ve seen the sky just begin to fall’ / He said, ‘All things pass into the night.’” The place where vocalist and lyricist meet on this track creates a shrouded divinity—indescribable, cryptic, but an alluring, abyssal maw of a thing. It’s a sublime little miracle—a graceful, bittersweet triumph that feels like what it must be to simultaneously feel like floating and sinking.

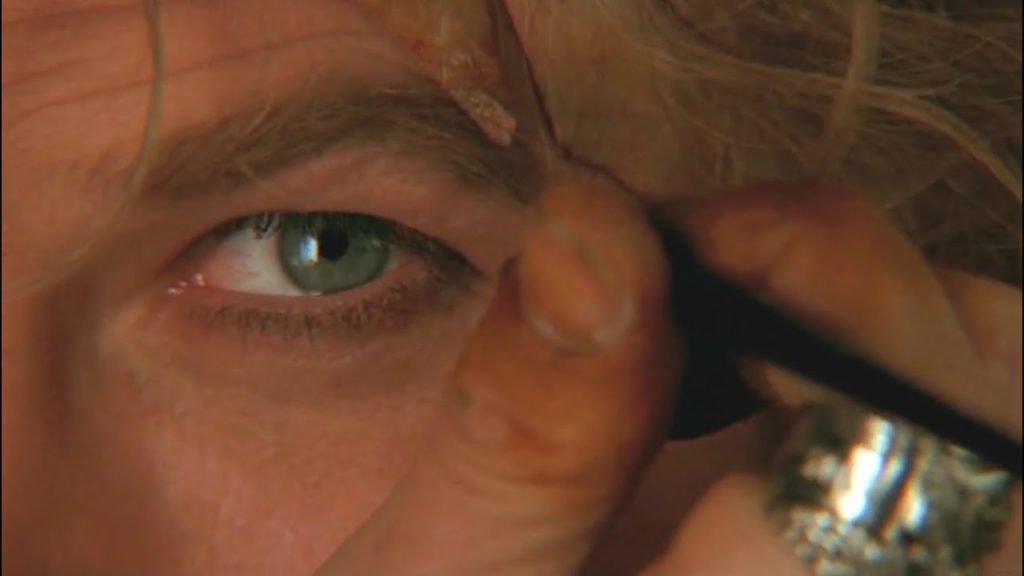

It’s no wonder that Jonathan Demme was so struck by this song—after hearing Q Lazzarus play it for him in the taxi she drove—that he put it in two consecutive films: 1988’s Married to the Mob and, in its most notable usage, 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs. It’s become this unusual cultural object in the wake of the latter, playing in a scene where the serial killer Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) primps and dresses himself in nothing but a thin scarf, makeup, and the scalp of a woman he has killed—providing him the long locks and hairline he finds himself without in his denial of sex reassignment surgery. Tak Fujimoto’s cinematography lingers on close-ups of Bill’s body—the crook of a hand where a tattoo of “LOVE” has been inked, a pierced nipple he tugs at, Bill’s lips mid-careful application of gloss. At the climax of the song, Bill flips on a camcorder and sashays in front of it, taking a moment to tuck his genitals between his legs, raising the scarf around his neck higher as Q Lazzarus’s vocals peak.

Demme’s characteristic reputation for complicated empathy rings somewhat strangely in his depictions of Buffalo Bill, especially in this scene. Bill, we’ve been told, is a vicious, unrelenting serial killer, one whose violent tendencies and history of cruelty were the reasons for his disqualification for sex reassignment surgery—“not transsexual, but he thinks he is,” as Hannibal Lecter puts it. Most of Bill’s appearances in the film are accompanied by the screams of his latest victim, Catherine Martin, just off-screen and held captive at the bottom of an empty well. We are never fully made to forget Bill’s capacity—and active behaviors—for bloodshed.

And yet, when the zenith of “Goodbye Horses” hits and Bill holds his pose, I can’t deny there’s a brief glimpse at an alternate life for Bill—a transcendence there never was. A transcendence he was never afforded.

It always surprises me how little Buffalo Bill is actually in The Silence of the Lambs—how fleetingly he’s on screen, how Demme’s portrait of him can only thrive on the negative space he leaves for the character and Ted Levine’s unnerving presence. How curious it is that we get so few glimpses into his interiority, despite the film’s main conflict revolving around him.

I chalk my surprise at his relative absence up to a kind of hyper-awareness—one where I and many other trans viewers have hardened our defenses at his pervasive reputation as a joke at our expense. There, too, Bill’s very being becomes more of a reflection of what he embodies culturally than anything Demme explicitly puts within the film. What he’s taken on in the lexicon far outweighs whatever the film provides him.

Our understanding of Bill as viewers—simply within the vacuum of the film—is an act that sidelines him. His own life and psychological realities soon become the focal point of Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter’s conversations, but always at a remove—as if a point of objective study, rather than a flesh and blood human with the emotional traumas and scarring that look to the social systems that create people like him. Even when their conversations turn to this very subject—Lecter suggests that “[Bill] was made [a criminal] through years of systematic abuse. Billy hates his own identity, and he thinks that makes him a transsexual. But his pathology is a thousand times more savage”—he becomes no more than clinical evaluation, his speculated history becoming marginalia just off-camera, because that implication does not fit within the boxes Lecter and Clarice are seeking to put him within. We only catch glimpses of the failings that make Buffalo Bill the person we see onscreen. We only live in the violent aftermath of those failings.

Without intending to—even if the intent was to exclude associations to trans people entirely—Demme, in positioning Bill as confused, makes it all too easy for those same pathologizations to fall toward how trans people are viewed. The attempt to leave space for that nuance, or to not speak for fear too much for trans people out of fear of misrepresentation, leaves too much space for the misconception to fester in the gaze of many cis viewers.

I recall—not any of the other notorious 1990s depictions of trans people that can only charitably be called “misguided”—but a passage from Joseph Stefano’s screenplay for Psycho that lands with a frightening prescience for how characters like Buffalo Bill, and many actual trans people, are often talked around by outsiders in the medical world. In the most angered state Norman Bates gets, he defends his own “Mother” persona by saying, “People always call a madhouse ‘someplace,’ don’t they? ‘Put her in someplace!’ What do you know about caring? Have you ever seen the inside of one of those places? The laughing, and the tears, and those cruel eyes studying you?… People always mean well. They cluck their thick tongues, and shake their heads and suggest, oh, so very delicately!”

As I was writing this short essay, I found myself incidentally discussing The Silence of the Lambs with a trans friend of mine, and she lent me a perspective that hadn’t crossed my mind: that the discussions characters have on Buffalo Bill’s gender must be taken with the grain of salt, especially those as definitively stated from a serial killer. The film, in its own way, becomes about how pervasive pathologization is—a rigorous system perpetuated by all sides, and prone to depersonalization of those who do not neatly fit a certain psychological profile.

I found myself struck, however, where I least expected it. In discussing Bill with Clarice, Lecter prompts her with a question: “How do we begin to covet? We begin by coveting what we see every day.”

In the days I had spent longing, more than anything, to be like a woman—to look like a woman, to be seen as a woman—it was the everyday reminders of what I wasn’t that haunted me most of all. I would come to obsess over the qualities that I wanted most in myself, the things that I started convincing myself would “make” me a woman. That which is in front of our eyes is, after all, that which is the hardest to ignore.

It’s the act of scarring that schisms each of our paths, whether those who make the wounds are familial, interpersonal, or institutional. But in the life I’ve made now—having found most of what I had wanted in my most hopeless days—what I feel is that we all have the possibility to transcend, to become more than we’ve ever been told is possible. If we were only given the grace of becoming—if only our existence didn’t hinge on those who would sooner look for reasons to box us out.

Q Lazzarus passed away in 2022, after disappearing from music and a public-facing profession entirely following the attention placed on “Goodbye Horses.” I often find myself wondering about whether this song holds the same power for others that it does for me—if others think about it as its own entity the way it deserves to be heard. Over the years, I’ve found myself drawn to the song in isolation more often than I have its place in Silence, engaging with it as the sublime object it is—seeking the resonance it holds on its own without its refractions in Demme’s lens. I’ve listened to it in the dark of a bedroom when unsure of myself, or who I wanted to be—seeking a shape in the same mysteries William Garvey’s lyrics possess. I’ve found quiet catharsis in reclaiming it through others’ delicate reinterpretations of the song.

When I think about Q Lazzarus’s legacy, and how strongly “Goodbye Horses” has endured—even well beyond Silence of the Lambs—I hope she knew how the song transcended the margins of this film. I hope she knew what it meant to people like me.

I’m still tracing out the shape of this song in the dark, long after the lights have been cut. Maybe I never fully will. That’s always been its magic.

Edited by Finn Odum