|Dan Howard|

Cure plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, October 8th, through Tuesday, October 10th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

I was first introduced to Kiyoshi Kurosawa back in January, when attending a screening of Pulse (2001). During the film, I observed something you typically don’t see in a lot of modern horror media: Pulse does not resort to jump scares, gore, or showing off a woman’s breasts to distract from the film’s overall lack of actual substance. It is the psychological horror that typically gets me on the edge of my seat more than any other type of horror film, and the more I watched Kurosawa’s Cure, the more I believe it ranks among the most thought-provoking horror films ever made.

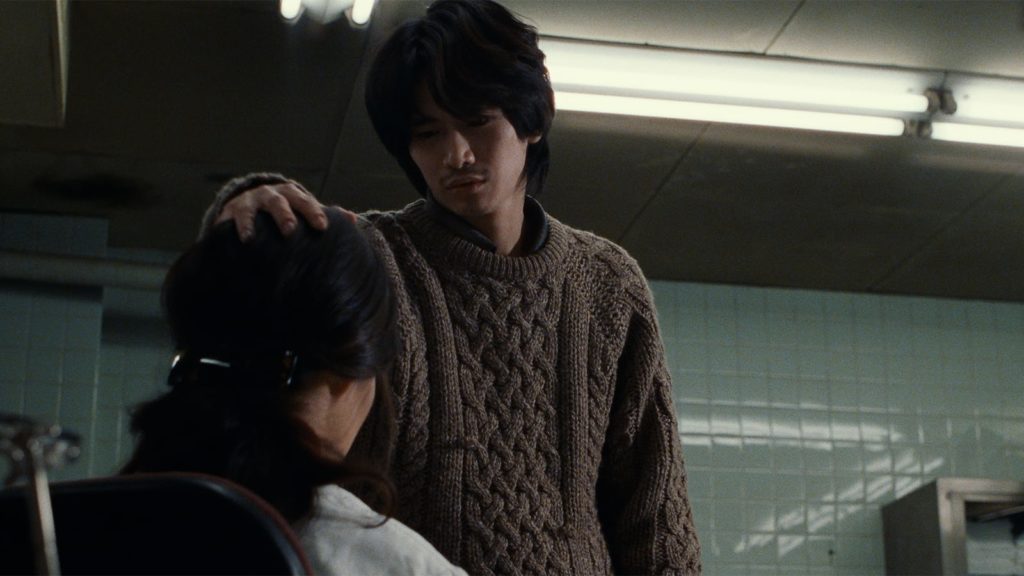

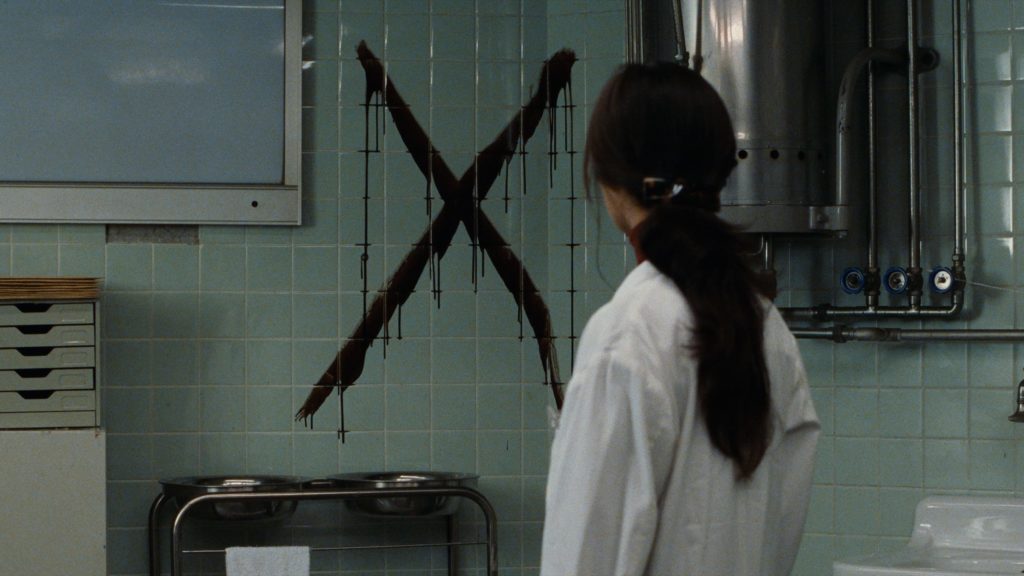

Cure follows middle-aged police detective Kenichi Takabe as he investigates a series of violent murders committed by random citizens who all claim it simply felt natural in the moment, leaving an X carved into their victims. When Detective Takabe hits a dead end, he hears about a man by the name of Mamiya, whom each of the killers encountered before committing their heinous crimes. Mamiya is soon believed to have put them under a type of hypnosis, driving them to their murders. However, when Takabe and Mamiya meet, a deeper mystery unveils a rage lying in both men, and though Mamiya has accepted his emotions, the detective is not ready to face his.

At its core, the film’s strengths lie in its uneasy sinister undertones—primarily those residing in Detective Takabe’s paranoia; the idea of “What could I be capable of?”—a paranoia that is heightened when the detective is alone with Kunio Mamiya. Cure is not so much a character study of either Mamiya or Detective Takabe as it is a study of the effects that untethered violence has on the human mind. By witnessing the victims completely break down upon the realization of their crimes, Detective Takabe subconsciously awakens the fear of his own suppressed hostility—a rage that Mamiya has seemingly embraced. As Mamiya uses a lighter to trigger the vicious characteristics of his victims, it is soon revealed to be much more complex than a psychopath being fascinated with fire.

Fire often symbolizes destruction. In this scenario, it symbolizes igniting a spark inside someone, and gives Mamiya’s victims a form of confidence and calm to enact their brutal homicides. I believe that is why most religions believe that humans are easily susceptible to an evil outside influence or, rather, the influence of the adversary. After all, the greatest trick that the Devil ever played was convincing the world he does not exist. At one point, another detective mocks Mamiya’s victims-turned-killers by suggesting they call the claim “The Devil made them do it.” Mamiya is a man with extreme short-term memory loss, oftentimes not remembering what was said to him mere seconds before, remembering nothing about his identity or his past. Much like the Devil, he seems to not know himself. Of course, this leaves the detectives to merely speculate. Therefore, the killers not remembering Mamiya at all could perhaps further that notion of Mamiya being a similar type of evil to the devil. The idea that Mamiya might be the Devil himself can be a bit far-fetched, but it made me contemplate the subject of facing your demons.

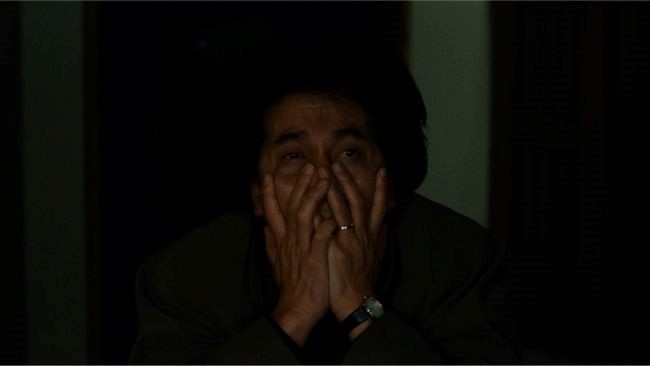

However, what happens when someone becomes conscious of these urges, attempting to resist, and the adversary takes notice? Takabe seems to be the only one with the willpower to push back on Mamiya’s efforts, and Mamiya certainly notices. We see the effect it has on Takabe’s mind. He knows he possesses that darkness in him and strives to maintain a sense of moral superiority over his adversary, something I think we all might relate to. Unfortunately, with Takabe’s endurance comes Mamiya’s fascination. Being the first one to really show resilience against his tricks, Mamiya slowly opens himself up to Takabe more and more, speaking of what he does remember and describing his current state of being: “All the things that were inside of me… Now they’re outside. And the inside of me is empty.” He even admits he sees himself in Detective Takabe, who acts as rationally as any one of us might when faced with someone we don’t quite understand and can bring out the worst in us. That alone makes Takabe a worthy opponent for Mamiya and worthy of being one of cinema’s most fascinating protagonists.

The more that is discovered, the more I believe that trying to understand exactly what Mamiya is, and how exactly he came to be the man we see in Cure, is the best part of the film’s mystery. Like The Silence of the Lambs before it, Cure explores an evil entity getting into our heads; that anyone could be a killer. Anyone could embrace the most disturbing parts of themselves and become just like our adversaries. Even Alfred Hitchcock once claimed: “There is no terror in the bang. Only in the anticipation of it.” Whether or not we witness someone turn into a killer and act on those violent impulses is not as terrifying as the mere possibility that they could and how close they come to it.

One of my favorite quotes about cinema comes from David Lynch, someone who is well versed in exploring dark subjects in his own works, providing us with this notion: “Not everything needs to be explained.” Just like most characters in Lynch’s works, Kunio Mamiya remains a fascinating enigma that I will continue to think about for years on end, trying to understand his character. Ultimately, the story of Mamiya and Detective Takabe is a cautionary tale of violence only spreading violence and that your own humanity must overcome the odds. That alone makes Kiyoshi Kurosawa an underrated master. Cure is undoubtedly one of the most terrifying masterpieces of modern cinema.

Edited by Finn Odum