| Chris Ryba-Tures |

The Cars That Ate Paris plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, September 15th, through Sunday, September 17th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

“There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another.”1

Walter Benjamin

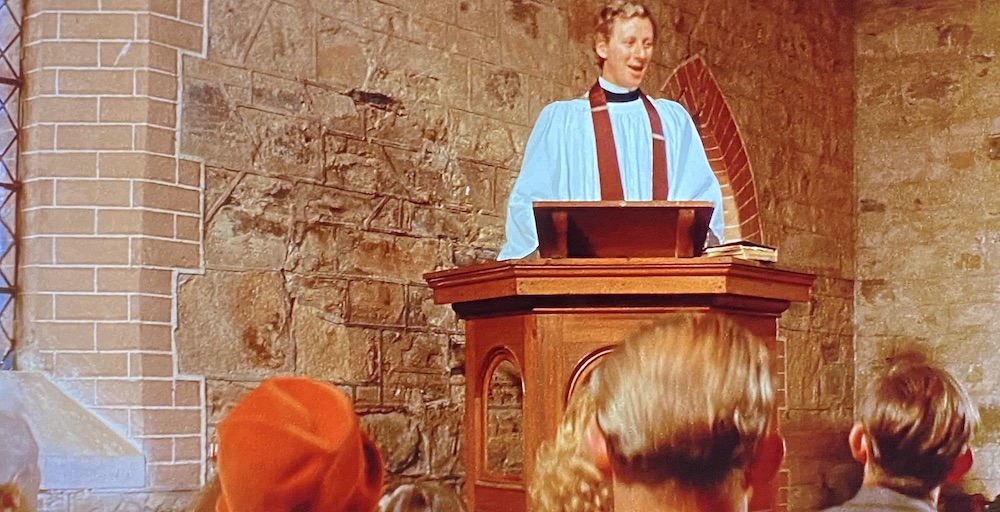

A rural priest turns his car down a narrow, unpaved highway, winding treacherously toward Sunday service in the Australian town of Paris, a backwater berg worlds away from its namesake. He’s running late. He notes that today, perhaps because of his hurry and the precariousness of the road, the hollowed-out carcasses of wrecked cars dot the pastures where one might expect grazing cows. As he enters the town, the grotesque, automobilic abominations of the rebellious youths—the hoons—make themselves known. Hoon and machine become one as they carouse recklessly about the town square as churchgoers gather in the pews.

“As you know, I have two hobbies,” the priest says taking the pulpit. “The past, which is manifest in these lovely old country towns like Paris, and the future which lies with our youth. And I’m very pleased to notice here that they’re having a car gymkhana (auto race) the Sunday after the [Paris Pioneer] Ball. It’ll give our youth the chance to blow off a bit of steam and share with us in our celebrations of our glorious past.”

“About the only criticism that I could offer as a newcomer,” he continues with a chuckle, “is your road: it’s a real boneshaker. I’d certainly hate to travel on it at night. I think that’s a part of your past you don’t really need to preserve.”

This last bit is met with one forced, performative laugh by the mayor, looking around nervously for his community to join him. No one does. There’s nothing to laugh at. The town’s entire economy thrives on that boneshaker of a road. The town’s history of community and meager prosperity has been built on the death and exploitation provided by that road. While the rest of the region suffers from economic hardship, the town of Paris has thrived by orchestrating car accidents, salvaging and repurposing what they can from the wrecks, lobotomizing or brainwashing the survivors, and building a new, patchworked cultural identity all their own. Without that road, without their predatory traditions, the town of Paris would die. The priest, serving here as the mouthpiece of pedestrian morality, is oblivious to all of this. He’s an outsider looking in, just like the viewer, seeing more than he should without fully understanding how or why this town is the way it is. After mass, he barely lingers long enough to greet his congregants before peeling out of town. Maybe he feels that something is off with this place. We sure do.

This seemingly incidental scene takes place at the exact halfway point—at the intersection of the past and the future—of Peter Weir’s 1974 genre-bending satire The Cars That Ate Paris. It’s a film that, much like the town of Paris, is difficult to meet on terms other than its own. At first glance, it’s a conventional, if not familiar narrative: the story of crystal-fragile protagonist, Arthur Waldo, a fish-out-of-water trying to make a place for himself in a small town full of secrets. But then there are all those gory car crashes; the gang of wildly dressed hoons in even wilder cars; the surreal Pioneer Dance animated by its jaunty, ascending four-chord loop; and the mad scientist subplot. Is this a horror movie? A dark comedy? A monster movie? A Western? A bizarro melodrama? Is this supposed to be scary? Campy? Funny? Disturbing? Yes. It’s all those things. Above all, though, it’s a meticulously detailed examination of the inevitable, violent collision of a colonial past and a future birthed from its inherent violence.

The automobile is a fully loaded metaphor for this tension: it is a symbol of status, mobility, power, and progress, as well as danger, destruction, and death. “It’s the world we live in,” the mayor says reflecting on our post-car accident trauma. “The world of the motor car.” Like the majority of the colonized world, an engine rumbles along the veins of commerce and culture. But in Paris, Weir has pushed the world of the motor car to its extremes via the microcosm of a small town—it is their livelihood, their bits for barter, their source of human stock for the next generation, fashion, home decor, ability to construct a pastiche of other cultures to claim as their own. Every set piece puts the anatomy of the automobile to marvelous practical use. They, like us, have lots of nice things with unsavory origins making up their daily lives. Watching the people of Paris enjoy the comforts their ill-gotten bounty affords them, it’s difficult to stifle a cringe—how many of the everyday creature comforts in my own home originated in slaughterhouses, sweatshops, mad laboratories, and de-forested jungles? Like the people of Paris, it’s best not to think about where these products came from. That’s the kind of shit that’ll wreck a conscience.

If you can get past the grisly circumstances, it’s kind of amazing to watch the intergenerational dance of Parisians working together in their makeshift chop shop, each having their own task of inspecting car parts and dissecting luggage contents. They all work deftly with practice and purpose. Nothing, save for the frames, goes to waste. It’s almost utopian. This is what their much-anticipated Pioneer Ball is celebrating. “The early pioneers suffered adversity and they overcame it,” says the Mayor, stoking the fire in the bellies of his fellow Parisians. “Only the strong survived, and the weak perished!” And the town of Paris, as small and absurd as it is, has grown strong in this idea of itself, surviving on the weakness of the highway traveler—crash after crash, year after year.

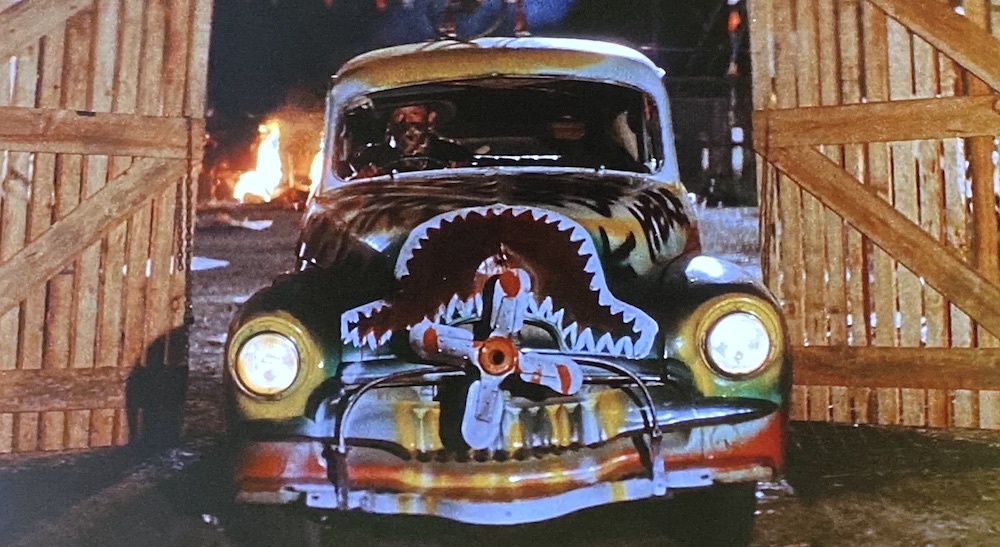

But the cars that have nourished Paris throughout the past have spoiled in the hands of the hoons (literally meaning a young man who drives recklessly). Murder, exploitation, and secrecy are also part of this legacy. And, as legacy dictates, the next generation finds self-expression and rebels using the same historical vocabulary in a new context. The hoons of Paris embrace the wreckage of their forebears, changing it from “something done to outsiders” to “something done to self or each other.” Perhaps this is all done out of fun adolescent boredom, but I see nihilism in it. They’re crafting a future with the only materials the past has made available to them: murder, materialism, racism, dehumanization, appropriation, and lies.

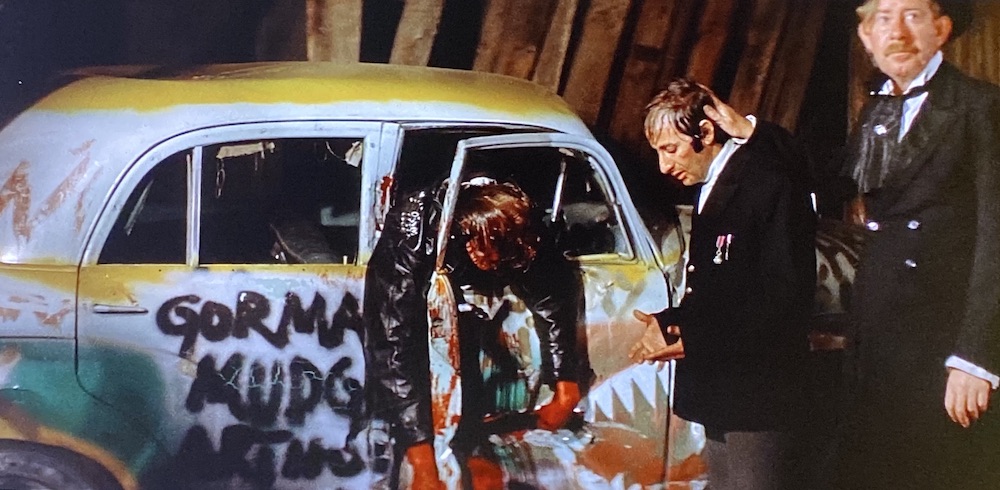

For most of the film, the hoons delight in a controlled form of destruction. Their cars are punk as fuck, truly rebellious (some to the point of being aggressively hateful), wildly artistic, and counter-cultural, particularly in contrast to the traditional, stodgy presentation of municipal leaders and their vehicles. So much so that the cars take on a life of their own. The humanity of their drivers is absorbed behind the windscreens, into the monstrous mien of each machine. In motion, they are strange and unpredictable, knocking into each other like lusty, drunken beasts. In fact, the hoons’ cars are the closest things to animals in the town of Paris. Weir heightens this by layering in animal growls under the roaring motors to great effect. And these beasts need to be fed—with the illusion of power, with free rein, with gymkhana—to keep them from devouring the town. Here too, we can see that civilization can easily be stripped of its refined veil, laying bare its subtle shadow self, its ever-present brutality, its always-lingering barbarism. A balancing act, rather than a balanced system in action. Just like our protagonist, Waldo, the more time we spend in Paris, the more unsustainable and downright volatile it reveals itself to be.

Near the end of the second act we get a closer look at the lines of decorum drawn between the authorities and the hoons to maintain a semblance of law and order in Pairs, and, by extension, see just how tenuous the fabric holding it all together really is. And shortly thereafter, following an act of automotive justice in which one of the hoons’ cars is set ablaze, the fabric begins to tear. Catastrophically so.

In the third act, Weir delivers on the promise of the film’s title. The eating of Paris is more than just the screeching climactic chaos of steel plowing through timbers and screaming citizens launching makeshift spears into the film’s final moments. We’re seeing the collision of the town’s former glory turned gory—how the world of the motor car as the town of Paris inhabits it, the exploitation and rationalization that kept the murderous town alive is eating it from the inside out. The priest did warn us.

Pulling myself from the psychological wreck over which Weir rolls the credits, I’m still thinking about the priest, his message, this nightmare collision of what’s come before and what comes after. The priest was our Cassandra at the pulpit and later, the avatar for the moral and spiritual death of the town. In the priest’s story and sermon, although brief in the film’s tight 90-minute runtime, Weir shows us through twisted metal, fire, and blood that the malignant aspects of a colonial history, no matter how attached to them we may be, must be relinquished, lest they consume us. Devastation is just the final course. Throughout its past, Paris, and in analog, the colonized world, has been choking down lies, salvaging scrap, and spitting out black exhaust. Its stomach hemorrhages with the mass accumulation of appropriated treasures and trinkets—mink house coats and racist Aborigine statues and scar-templed orphans—and spills poison fluids into the ground. On the radio, under the blaring, garbled, old-school war cry, the keening of a dying engine, and under that, a death rattle.

Bibliography

1 Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections [ed.] Hannah Arendt, [trans.] Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 2007 [1955].

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon