| Matthew Lambert |

The Cars That Ate Paris plays at the Trylon from Friday, September 15th, through Sunday, September 17th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

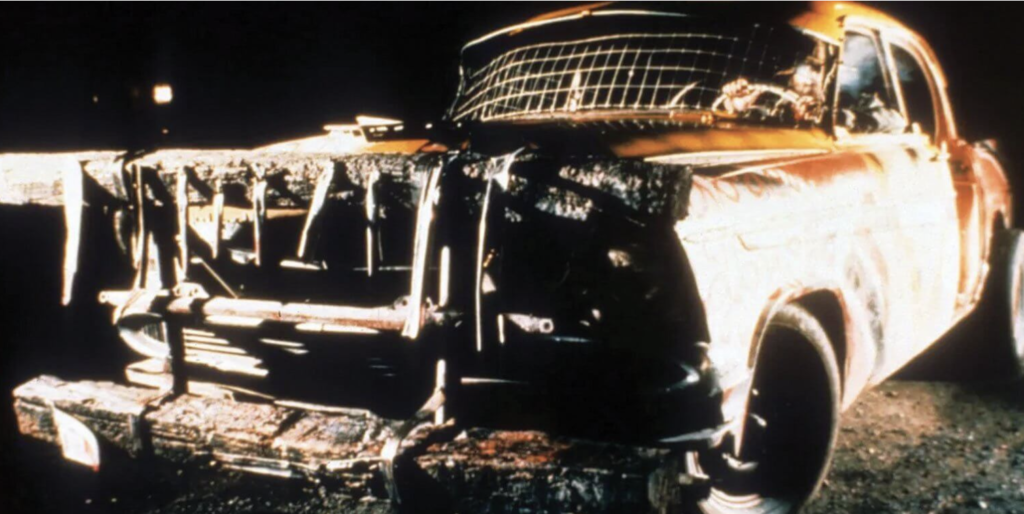

There’s a quintessential moment of madness in the 1974 low-budget horror film The Cars That Ate Paris that is seared into my brain. It’s Charlie (played by the ultimate Australian character actor Bruce Spence) standing outside his fortress of wrecked cars, blood stains on his shirt from the latest car crash victim of the windy Paris dirt roads, dangling hood ornaments over his mouth like a bassinet. The cars of Paris represent not only a livelihood but a proclivity that Director Peter Weir tries to address in his film debut.

The Cars That Ate Paris follows Arthur (Terry Camilleri), who arrives in Paris after a car crash that results in his brother’s death. The Mayor (John Meillon) convinces Arthur that he should stay in Paris, since he has no family and no place to go. Once released from the hospital, Arthur learns that Paris’s economy is based around the frequent car crashes that happen outside of town. The townspeople claim, trade, and sell pieces of the wrecked cars to sustain themselves. The victims of the car crash, if they are severely injured and are still alive, are experimented on by The Doctor (Kevin Miles). While the older generation of the town is quite satisfied with their murdering ways, the teenagers of Paris are not sharing the crashed cars. Instead, they’re building cars that can be used to do the killing themselves and to take Paris as their own. Arthur finds himself trapped in the outback town because he’s unable to operate a car himself after being convicted of vehicular homicide years ago.

To understand why The Cars That Ate Paris is more than just a fun, breezy b-movie, it is important to understand where Australia’s car culture itself was in the 1970s. I feel like a disclaimer is in order: I’ve never been to Australia, though I would love to go someday. But this terrific country has accessible statistics that comprehensively paint a picture of the epidemic facing the citizens of Australia for multiple decades. Between 1965 and 1982, there were 62,430 fatal crashes in the entire country. The high number of those fatalities came in the 70s, when nearly 4,000 people died in 1970 on the road. While fatalities have plummeted in the new century, more Australians died in car crashes than in World War I, World War 2, and the Vietnam War combined. America was actually going through a similar trend in the 70s. In 1972, there were 54,589 fatalities on American roadways, the highest mark in our country’s history. But after watching the young people die in dangerous crashes, Australia actually addressed the issue by issuing stricter licenses and investing in creating safer roadways (the victims of Paris would’ve appreciated this.)

While Australians and Americans were dying in car crashes, Hollywood film studios embraced car culture and made it their own. The Criterion Channel has a playlist of 70s car movies like Duel, White Lightning, Gone in 60 Seconds, and Thunderbolt and Lightfoot—an illuminating snapshot of how the world viewed the power that vehicles represented then and how their influence is still felt today. Even a movie like Barbie can’t get around filming an entire Chevy commercial in the middle of the movie. The most obvious comparison of this film’s car-centric themes are the Mad Max movies. The Cars That Ate Paris doesn’t quite match the eye-popping excitement of those films, but it still shows Australian directors were trying to make sense of their current environments at that time.

It may be a stretch to say The Cars That Ate Paris takes on the automobile industry and makes people consider riding a bike to work. Clearly, the car executives have won. We are at their mercy. But the greed and corruption portrayed in The Cars That Ate Paris isn’t far from our reality. Maybe there isn’t a Charlie, blood-soaked and laughing as he adds spikes to the cigarette-smoking victim’s car that was claimed at the beginning of the film. But people do dedicate much of their livelihoods and identities to their vehicles on a regular basis.

The Cars That Ate Paris is a satisfying debut by a filmmaker working on a budget that may have been close to my annual non-profit salary. Comparing this film to Witness or The Truman Show isn’t that far off, ideologically speaking. Weir’s films are always dubious of the prevailing power structure. He’s always questioning the motives of those in charge and the reality his characters live in. The teens are an exaggerated and extreme version of an audience avatar. They steal the show in this film, forcing most of the adults in the town to ride in the backseat of their murder wagons.

Edited by Olga Tchepikv