| Yuval Klein |

Irma Vep plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, May 21 through Tuesday, May 23. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Viewers are immediately inundated with the multitudinous clamor of pre-production for an independent French film. It is somewhat humorous, somewhat curious, and somewhat stress-inducing. Then, Maggie Cheung, a well-mannered Hong Kong movie star, enters the room. The genre-bending realism immediately engages viewers. The crew of the film greet Maggie, and then wonder where the film director is. Jean Pierre-Leaud is the personification of the French New Wave, the personality of French Cinema, and so it was vital for him to play René Vidal, the antiquated French filmmaker at the helm of this project. This role as a neurotic, pretentious, insular but passionate director of a Les Vampires (1915-1916) remake is hysterical. The other most famous French film about filmmaking also happens to star Jean Pierre-Leaud.

Maggie Cheung plays a character that is going through a similar experience. The character is ostensibly herself, but she is nonetheless a scripted role in a fictitious story. She is a famous actress in the Hong Kong film industry, and she goes to star in an indie production in France, a remake of a French classic by Louis Feuillade (Les Vampires). Irma Vep is the name of a femme fatale gangster in the French criminal underworld that is pursued by two friends attempting to uncover her gang, “Les Vampires.” Rene does not paint a sordid picture of Irma Vep; rather, he puts more of an emphasis on the grace and femininity of the character. The casting of Cheung as Irma Vep is peculiar not only because of her national origin, but also because Irma Vep is a vile and dangerous woman, whereas Maggie is seemingly more gentle by nature. Later, it is Maggie who tries to convince René of Irma Vep’s power after he has a nervous breakdown. For René’s filmmaking friend, José Mirano, Irma Vep is the embodiment of street-wise Parisians. As René mentioned, she is just an “idea.” The meaning of Irma Vep is inflated with every mood shift and conversation, so it would be pointless to declare her to be one thing.

I should mention that Olivier Assayas reimagined the world of Irma Vep with the new HBO miniseries from 2022 that incorporates the stories of Les Vampires, the 1996 Irma Vep, and a new fictitious production reimagining of the composite universe. It is just as refreshing and playful as the 1996 film. Assayas first garnered attention and acclaim for his film Cold Water in 1994. Irma Vep was the next work after this breakthrough movie. It has a playful quality of interwoven genres and cinematic techniques that distinguishes it from other films, whether that be French or foreign, indie or well-financed. He has become one of the most distinguished contemporary French filmmakers and often returns to the behind-the-scenes setting in his works.

In Maggie and Rene’s first meeting, Rene tells her that he had no intention of doing a remake of Les Vampires when the project was initially introduced to him. He thought that no actress had what it takes to capture Irma Vep (other than the original Musidora in Feuillade’s 1915-16 serial)—that is, until he thought of her. So he said that he would make the film if she would play the part. Just as it is imperative to René that Irma Vep is played by Maggie, the same applies to Maggie playing the role of the protagonist in Olivier Assayas’ vision. These parallels make the behind-the-scenes aspects of the film more intriguing, and Assayas utilized this wonderfully in the previously mentioned miniseries remake/elaboration of the film.

The costume designer, Zoé, is in close contact with Maggie throughout the production. Zoé is given an absurdly trashy reference photo for the Irma Vep outfit. She initially complains that this is a hooker’s outfit, but she acquiesces after Vidal insists. She is (along with René) another caricature of French dissension, as she trashes popular culture, shrugs off admonishments by her superiors, and takes drugs. Zoé is headstrong. Every time that she is scolded by the director, she answers back with an insolent reproach. Maggie is passive, affable and pleasant, so she does not succumb to petty reprisals. The contrast between Maggie and Zoé is representative of the cultural differences between the French and Chinese/British.

Assayas was a film critic before becoming a director, and so evidently, there are a lot of dialogues on the state of cinema throughout the film. One of the recurring discussions is that of French vs. foreign (especially American) cinema. Zoé says that she doesn’t like American films, that everything is too much decoration, too much money, and for “nothing.” Maggie does not argue out of politeness, but certainly does not agree with her. Zoé also protects her friend’s old “cinema militante” movie although the directors themselves think that it is outdated, and when the ending scene of their movie is shown, the audience has to agree that it is a pretentious and kitsch film.

Maggie visits Rene Vidal after a fight with his wife that ended in police intervention. Vidal broods about the futility of remaking what has already been done, and that the image of her as Irma Vep was just very exciting, but he is not able to make this idea, and so he is stuck in a frustrating quandary. Again, the idea of Irma Vep is malleable, as are those regarding cinema. Leaud plays this scene with a phenomenal intensity full of melodrama and comedic sensibilities.

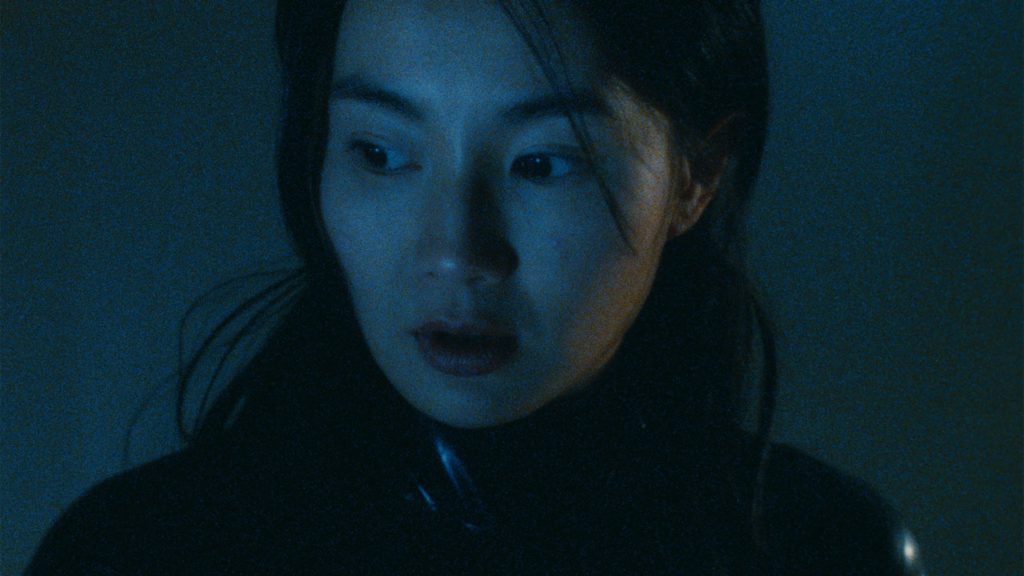

Then, there is the iconic lurking scene, in which Maggie essentially becomes Irma Vep. In the hermetically sealed outfit of the character, she creeps up the stairs with the railing silhouetted on the walls beside her and passes through the doorway of a room that the hotel maid had entered to briefly clean. The maid shuts the door behind her and Maggie is now alone with a naked woman who is in the midst of a contentious conversation with her partner. Beside the sink, Maggie spots a stash of jewelry. She picks it up and closes the door behind her in one discreet and brisk motion; then, when she hears people walking by, she bursts farther up the stairs and finds herself on a rainy rooftop. Thunder sounding amidst the pouring rain, Maggie averts her attention to the jewelry in her hands. She lifts it into the air and drops it off the building. This is a truly dazzling and enigmatic scene. It may represent the simultaneous freedom and vileness of Irma Vep’s character. Also, because Irma Vep is a symbol of the Parisian criminal streets/underworld, she could be dropping her refined personality to crumble on the streets beside Irma Vep. The allegorical intentions of Assayas are hidden in ambiguity, but it is nonetheless an enchanting moment.

The ending is a sequence taken from René Vidal’s edit of his remake, which has shapes and jagged lines superimposed on the Les Vampires reenactment scenes. With Maggie Cheung’s distorted image in the background, an avant-garde series of visual and auditory tumult concludes the film in the most iconic and inimitable of ways.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon