| Luke Mosher |

The Trial plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, April 21 through Sunday, April 23. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Franz Kafka’s 1925 novel The Trial begins like this: “Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested.”1 There it is—the whole maddening tale, captured in a sentence. K., whose name has since become a cultural symbol for bureaucratic oppression against the individual, is arrested but never told what his crime is or who his accusers are—even his last name is obscured. It’s a real nightmare of a premise. Orson Welles’ 1962 adaptation of The Trial is one of the few films that’s successfully captured the vision and vibe of Kafka’s surreal fiction and remains one of the best depictions of the Kafkaesque on screen.

Briefly, the story: As established, Josef K. (a perfectly cast Anthony Perkins) is arrested for an unnamed crime. Strangely not jailed, he is left to wander the city, also unnamed but vaguely European. He runs afoul of co-workers, bureaucrats, and bothersome family members while trying to deal with his trial, which, apart from one arresting courtroom scene where K. defends himself with Mr. Smith Goes to Washington levels of passion, mysteriously occurs offscreen. His uncle Max (Max Haufler) convinces him to seek council with the lawyer Hastler (Orson Welles himself), who also calls himself, somewhat enigmatically, The Advocate and conducts his business from bed. K. also has a handful of flirtations with women he meets, who seem to pity him. Seeing other hopeless defendants who have waited years without hope for their own trials, K. eventually dismisses The Advocate, taking his case into his own hands, which leads the story to spiral out of control in a frantic denouement.

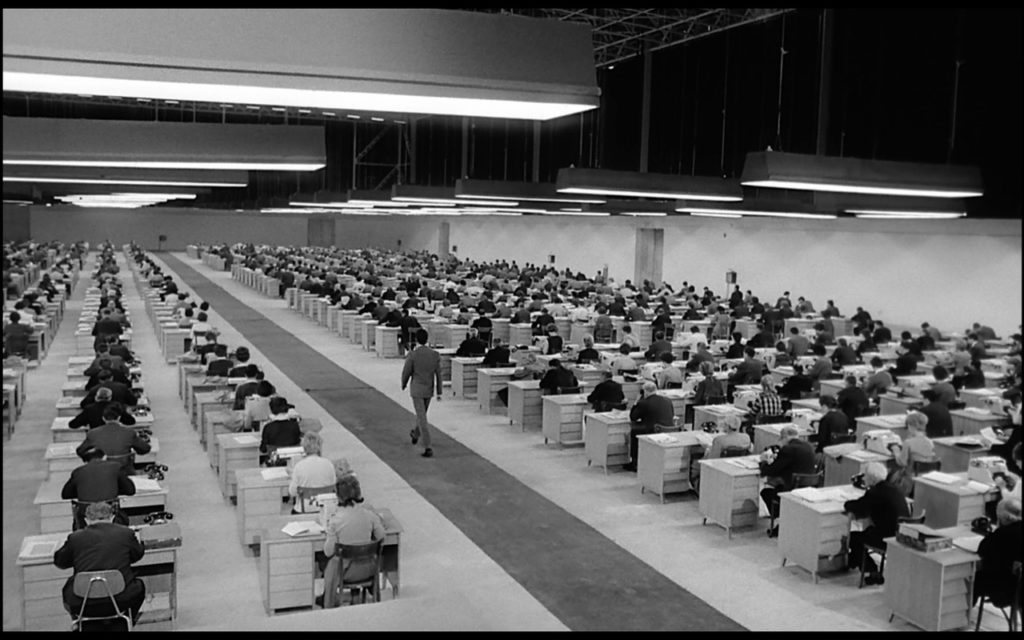

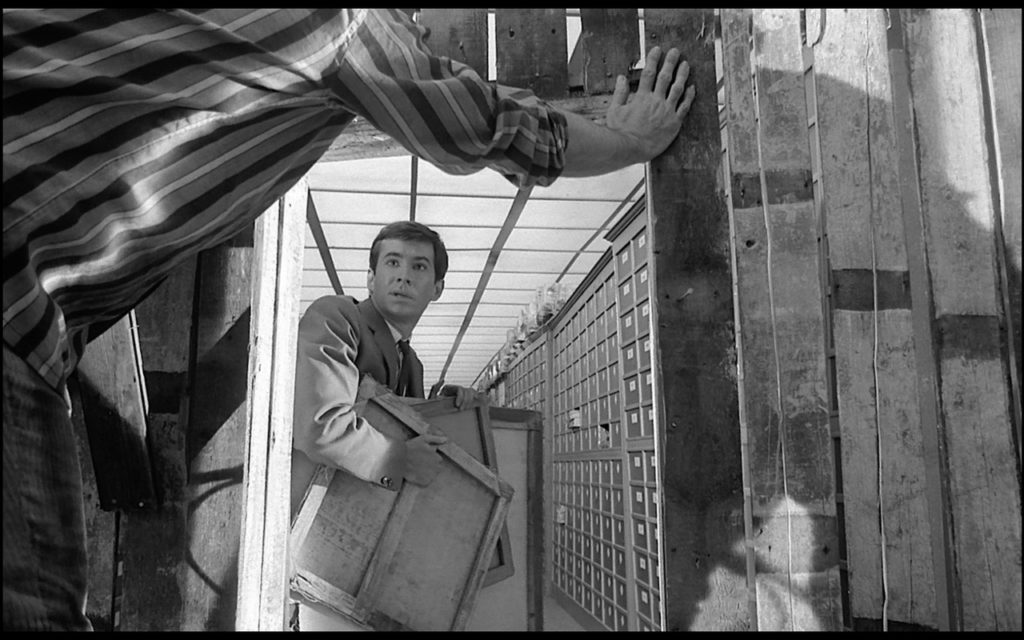

As the prologue of the film points out, the whole thing feels like a nightmare, and that impression is the film’s strongest quality. Absolutely everything we see in The Trial is dedicated to making K., and us, feel disoriented, uncomfortable, and alienated. Welles’ use of space shows K. dwarfed against brutalist buildings, which look empty from the outside but are stuffed with people on the inside. Other spaces are cramped, like the low ceilings in K.’s apartment or the portrait painter’s roost-like atelier. K. wanders through locations that seem to morph into other locations like a dream. Staircases bend at weird angles like Piranesi’s prison paintings. Sets are lit in dramatic light and shadow. Welles deliberately used exposures that made high contrasts and had a rule that light sources should not be identifiable to the audience. He also painted shadows on backgrounds to make them darker.2 There is also strange time dilation, like when the policemen pull K. from the opera to interrogate him “outside working hours,” but afterward, when K. goes back to his office, he finds his army of employees still hard at work. This office set especially, a giant room filled with a staggering eight hundred and fifty office workers with desks and typewriters,3 is one of the most vivid images Welles ever created, and rivals The Crowd (1928) and The Apartment (1960) as one of the best “giant office” sets that so effectively capture the depressing humdrum of modern office work. When designing the set in pre-production, he told the art department, “I want it to run to the end of the world.”4 And of course, Welles, the great Leonardo of film, pulls from his deep bag of tricks that make pure cinema like this so much fun to watch: long takes, deep focus, dynamic staging, Dutch angles, and a camera that chases K. doggedly through the film.

Many of these elements were already present in Welles’ own hallmark style. His theatrical expressionism made even his dramas feel like thrillers, and was on full display in his previous two films, the pulpy international crime caper Mr. Arkadin (1955) and the rugged noir Touch of Evil (1958). But new to Welles’ filmmaking vocabulary in The Trial is a surreal, arthouse quality more reminiscent of the avant-garde European films released around the same time from directors like Alain Resnais or Jean Cocteau. In interviews, Welles admitted to disliking Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) and Last Year at Marienbad (1961) (“I mean, I don’t like them, but I’m so glad that they were made”5), but still, the artistic similarities are there; there was simply something in the water in mid-century Europe.

The Trial was the first feature adaptation of Kafka’s work, and the unique cocktail of aesthetics that create its “existential thriller” atmosphere would set the tone for what Kafkaesque films would look and feel like. Think of Godard’s Alphaville (1965), the Coens’ Barton Fink (1991), Richard Ayoade’s criminally underseen The Double (2013), or pretty much anything by David Lynch—they operate on the same wavelength as The Trial and draw stylistically from it. Of course, for my money, the most Kafkaesque film is Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), which has a similar story and feels like The Trial reflected in a funhouse mirror. But what does that term mean, exactly—Kafkaesque? I like this definition: “a situation in which an ordinary, innocent individual is at the mercy of anonymous, bizarre and frightening forces, usually in the form of a malevolent or indifferent state bureaucracy.”6

As an idea and an aesthetic, the Kafkaesque has endured because so much of modern life is Kafkaesque. Welles called it “Kafka’s clairvoyant view of the future.”7 Having a phone call transferred between representatives who can’t answer your question, filling out the never-ending forms involved in changing your legal name, and dealing with the U.S. healthcare system (which is probably the most Kafkaesque system ever devised besides maybe the Soviet Union) are all everyday manifestations of it. It is the inevitable result of any bureaucratic system bloated beyond functionality. Kafka sensed it when he began the novel in 1914‘s Prague, and we’re still living with it today.

However, I’d like to suggest that Kafkaesque bureaucracy is merely the setting, and not the subject, of The Trial. The film opens with a parable: a man seeks “the law” but is barred from entering by a guard. He grows old, and finally dies, still outside. There are many themes that run through The Trial, but this one, guilt before an inaccessible law, is the one that stands out the strongest. K.’s predicament, his defensiveness against unknown charges and his feeling of vague guilt, is a strange part of the human condition, and I suspect that it is the way we all secretly feel—or at least I do, as did Welles, who said so in interviews about why he was drawn to adapt the novel.8 K. asks, over and over, what crime did I commit, and against whom? Is it God, or society, or the government, or an individual person—or maybe all of them? Never gaining access to “the law” means you can never defend yourself or seek justice, and thus the guilt remains, never to be erased. If that seems harsh, welcome to the wonderfully dour world of Franz Kafka.

K. steadfastly maintains his innocence. But is he really guilty or not? The novel reads as if he isn’t. In the film, however, though there is no “Rosebud” revelation that definitively solves the mystery, the subtle implication is that he is. This is all subtext, so feel free to toggle between both options (which the film invites you to do), but entertaining the idea enriches the viewing experience. Nearly every scene has some element of accusation or guilt; it hangs over the film like a noose. As Welles does so well throughout his work, he draws out the complexity of K.’s character, making him both a victim of the system and yet a participant in it. For instance, a few stray remarks from K. about his neighbor’s illicit activities cause her to be kicked out of her apartment, and later, his accusations that he was extorted by the policemen who arrest him cause the same policemen to be stripped of their post and beaten. Within the logic of this world, swift and merciless justice is carried out for even minor infractions, so somewhere along the line, it’s likely that, as his neighbor Miss Bürstner (Jeanne Moreau) puts it in an early scene, “You must have done something”—he just doesn’t know what. What matters more to Welles is his response to his accusation. Kafka’s K. is a submissive victim to his fate, but Welles’ K., though he is unnerved by his predicament, ends up a defiant anti-authoritarian.

K.’s complexity is brilliantly embodied by Anthony Perkins, an essential element to the film that I don’t want to overlook here at the end. As an actor, Perkins excelled at playing characters that were easy to pity but had dark and hidden depths, like Norman Bates in Psycho (1960), another character who projects innocence but harbors secret guilt. The success of The Trial, apart from Welles’ direction, is owed to Perkins’ performance. His sympathetic portrayal of K. is what grounds the film and makes sure it never fully gets lost in its own surrealism.

There are many ideas at play in The Trial, a film rich in detail and expression. The story plays at the edges of metaphor in the way so many great art films do. Each character, each scene, feels like it could also be a symbol of some larger idea. And still, the central conceit of the film, a man guilty of a crime that’s never named and caught in a bureaucratic system that carries out justice mercilessly, feels relatable and contemporary. K. is the Everyman that we can read ourselves into, and we are still living in his world.

NOTES

1 Franz Kafka, The Trial, trans. Breon Mitchell (New York: Schocken Books, 1998), 3.

2 Simon Callow, Orson Welles: One-Man Band (New York: Viking, 2015), 351.

3 Frank Brady, Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles (New York: Scribner, 1989), 529.

4 Callow, Orson Welles: One-Man Band, 350.

5 Orson Welles, interview with Huw Wheldon, BBC Television, September 16, 1962.

6 “Kafkaesque.” In Brewer’s Dictionary of Modern Phrase and Fable, ed. Adrian Room and Ebenezer Cobham-Brewer. 2nd ed. (London: Cassell, 2009).

7 “Filming The Trial,” YouTube, October 10, 2012, video, 1:31, https://youtu.be/RbUe-bM6bXg.

8 Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Nightmare as Funhouse Ride: Orson Welles’s The Trial,” May 11, 2022, https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/2022/05/nightmare-as-funhouse-ride-orson-welless-the-trial/

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon