| Nick Kouhi |

Days screens as part of the Slow Cinema series at the Trylon. This series, programmed by the Moving Image, Media, and Sound Studies Graduate Group at the University of Minnesota, is presented in collaboration with the Trylon Cinema. Tickets are free and available on a first-come, first-served basis. Scroll to the bottom of this page for more information about this series and ticket availability.

The body is no longer exactly what moves; neither subject of movement or the instrument of action, it becomes rather the developer of time…

Gilles Deleuze[1]

[A]s soon as an image or a face is captured on film, it will no longer age. I am looking for a face that is chosen by the film to live in its reality….

Tsai Ming-Liang[2]

In the 2015 documentary Afternoon (Na ri xia wu), filmmaker Tsai Ming-Liang begins his conversation with actor and longtime muse Lee Kang-Sheng by remarking on the latter’s toes. They’ve turned a yellowish color, Lee explains, from the sulfur he uses to “stop [them] from rotting.” Decay permeates the urban environments which house Tsai’s lonely figures; their human fragility typically conveyed through long takes with a static camera. While Tsai’s inimitable brand of Slow Cinema can make for discomfiting, even grim, viewing, it asks us to regard the multivalent value of the human body through poignantly recognizable visions of labor, sex, and aging.

In his essay Wastrels of Time: Slow Cinema’s Laboring Body, the Political Spectator, and the Queer, Karl Schoonover writes extensively on what he calls the “slow art film” and the labor often practiced by both the subjects onscreen and the viewers in the audience. He argues that Slow Cinema “speaks to a larger system of tethering value to time, labor to bodies, and productivity to particular modes and forms of cultural reproduction.”[3] The desire of the spectator, he reasons, is primarily “to clarify the value of wasted time and uneconomical temporalities” when watching films designed for “broadening what counts as productive human labor.”[4] Watching as work is a cultural practice long associated with the intelligentsia of the art world, which raises the question: if labor is practiced by an affluent audience when watching slow films largely about the working class, does that labor culminate in empathetic identification with the subjects on screen? Or does it result in self-satisfaction at engaging with “high art”? It’s impossible to ascribe a definitive answer to something as polymorphous as audiences, but it is worth considering how a filmmaker’s aesthetic decisions affect the viewer’s relationship to a cinematic avatar.

This preamble is meant to consider the ways Tsai Ming-Liang portrays the human body as a symbolic vessel for both social critique and audience identification. When it comes to physical labor, his characters are frequently seen cooking, washing, and cleaning in both the private and public sphere with the same degree of unceremonious habitude. While the function of routine within our lives aims to provide order, it can also constrict us within increasingly isolated social roles. The most despairing realization of that anxiety in Tsai’s filmography is arguably found in 1997’s The River (He liu), whose central family barely shares any screen time together. When they do, they’re united by pain, specifically the kind afflicting Hsiao-Kang (Lee) in his neck following a dip in the Tamsui River as an extra for a film shoot. The extended shot of Hsiao-Kang floating in water while the dummy he’s replaced lies in the bottom of the frame subtly foregrounds the ethical question of a filmmaker’s responsibility toward their subjects and collaborators.

Tsai’s films rarely answer this question in a didactic manner, instead letting the audience sit with the disquieting ambivalence symptomatic of late-stage capitalism. While I wouldn’t reduce Tsai’s convictions to mere Marxist dogma, his transition toward more esoteric media installations has been attributed, in part, to a dissatisfaction with traditional sources of film funding. His 24-minute short Walker (2014) tracks Lee dressed as a modern incarnation of the 7th century scholar and monk Xuanzang slowly walking barefoot across Hong Kong. The dialogue-free film acts, in Tsai’s words, as “a conscious act of rebellion against the way cinema is perceived in today’s society.”[5] It does so by beckoning our attention to Lee’s protracted gait through real crowds, reacting either with indifference or bemused puzzlement.

Yet Tsai’s recusant impulses find their most transgressive output in The Wayward Cloud (Tian bian yi duo yun, 2005). Tsai reunites the characters from 2001’s What Time Is It There? (Ni na bian ji dian) for an oddball musical romantic comedy where a woman (Chen Shiang-Chyi) discovers that Hsiao-Kang (Lee’s moniker in most of Tsai’s features) has professionally transitioned from watch salesman to porn actor. Tsai’s aesthetic strategy in the film adopts an atypically florid visual grammar, particularly during the musical numbers that further the fantastic surrealism of similar song sequences from 1998’s The Hole (Dong). But shot duration is characteristically protracted during a grotesque moment of (literal) climax. Shiang-chyi discovers Hsiao-Kang’s profession shortly before witnessing him rape his unconscious co-star at the behest of the film crew. While a visceral variation on the aforementioned shot from The River, the results couldn’t be more different; when Shiang-Chyi moans in simulated pleasure, Hsiao-Kang leaps up from the bed to ejaculate in her mouth, holding his member there for an uncomfortably long time.

Sex in Tsai’s films usually operates as a perfunctory act for his characters. At worst, as in The Wayward Cloud and The River, it starkly allegorizes the dehumanizing conditions of Taiwan’s rapid industrialization following decades of martial law under Chiang Kai Shek’s Kuomintang (KMT) Party.[6] Yet subtlety is not exclusive from sensationalism, as is the case in the climactic shot of The River where Hsiao-Kang performs oral sex on a stranger in a sauna, a stranger we gradually realize is his father (Miao Tien). This moment unspools in a single, unbroken take where faint flickers of light slowly bring clarity to what we’re watching, and nearly identical placement of both actors within the frame reifies a moribund element to the disturbing encounter.

Tsai’s own status as a gay man doesn’t neatly couch his work under the label of Queer Cinema, though it does reinforce his sympathy, if not empathy, for these intimate same-sex male encounters. In I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone (Hei Yan Quan, 2006), Lee plays a vagrant who is attacked in Tsai’s native Malaysia by a gang of hoodlums. He’s nursed back to health by a Bangladeshi migrant worker (Norman Atun), who helps him urinate in a striking shot devoid of sentimentality. In Tsai’s latest feature Days (Rizi, 2020), a climactic sex scene between Hsiao- Kang and a Thai masseuse (Anong Houngheuangsy) in Bangkok provides a cathartic release for the former, who seeks to alleviate his resurgent chronic neck pain. These shots could be deemed excessive, either in terms of their content or duration. Yet as Schoonover argues, “dickering over the use-value of the excessive image” makes us as viewers run the risk of “taking a referendum on queerness, questioning the validity of queer lives.”[7] By refusing to conform to a singular expression of queerness, Tsai’s camera privileges us with unadorned images of frank vulnerability.

That vulnerability is contingent upon the temporal transformation of Lee’s body throughout Tsai’s own corpus. “I am using the body of Lee to have a conversation with the world,” Tsai told Cineaste in 2019. In August of this year, Tsai told Film Comment

I suddenly realized that because of the aging process, the body is ever-evolving. I can see that inevitable evolution in Lee’s exterior, and that also prompted me to see myself as part of this aging process. He almost served as a mirror.[8]

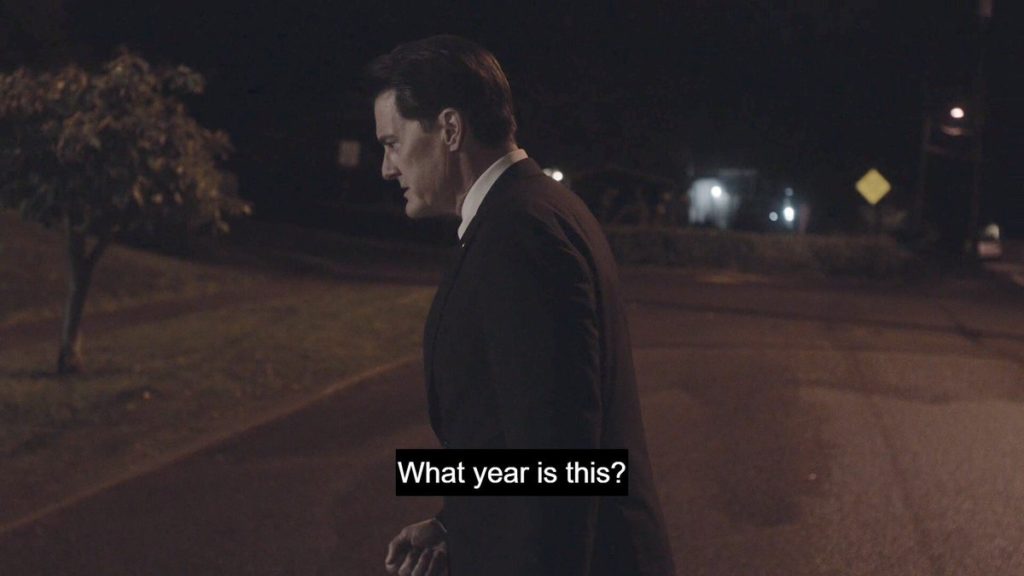

The use of an actor for a filmmaker to remark on their own mortality is most explicitly linked to Tsai’s cinema through the collaboration between François Truffaut and Jean-Pierre Léaud.[9] More pertinent to slow cinema is David Lynch’s depiction of his alter ego in Kyle Maclachlan in Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). Watching the aged Dale Cooper in a stupor for most of the show’s eighteen episodes, the spectator begins to ponder their own relationship to nostalgia for Machlachlan’s dashing hero and subsequently contends with larger questions of mortality in an alien, amoral America.

The darkness of Tsai Ming-Liang’s slow cinema is equally exacting. Yet his most moving tribute to the human body occurs near the end of Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Bu san, 2003) as the nameless ticket-seller (Chiang, once again) limps up and down the steps of the theater she’s sweeping for the last time. As she slowly hobbles on a lame foot with broom in hand, Tsai’s unbroken wide shot compels us to watch from a respectful distance with total attention. Her work as a character mirrors ours as spectators, aiding us in recognizing the labor we put into the thing which give our lives meaning. Tsai Ming-Liang’s generous cinema transcends a capitalist metric of valuing time and labor to transform the political into the deeply personal.

Edited by Michelle Baroody

NOTES

1 Deleuze, “Preface” in Cinema 2: The Time-Image (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), p. xi. 2 Tsai Ming-Liang. Interview with Erik Morse. “Time & Again.” Frieze no. 137. March 1, 2011. https://www.frieze.com/article/time-again.

3 Schoonover, Karl. “Wastrels of Time: Slow Cinema’s Laboring Body, the Political Spectator, and the Queer.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 53, no. 1 (2012): 68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41552300.

4 Schoonover, 65.

5 Tsai. Interview with Maria Giovanna Vagenas. “Filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang says his work should be appreciated slowly.” South China Morning Post. August 27, 2013. https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/arts- culture/article/1299497/filmmaker-tsai-ming-liang-says-his-work-should-be-appreciated.

6 Indeed, a statue of Chiang is seen several times in The Wayward Cloud, drawing an explicitly historical reference point for Tsai’s otherwise relatively subtle sociopolitical critiques.

7 Schoonover, 73.

8 Tsai. Interview with Devika Girish. “Interview: Tsai Ming-liang.” Film Comment. August 16, 2021. https://www.filmcomment.com/blog/interview-tsai-ming-liang-days/

9 Tsai has frequently cited Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (Le Quatre Cents Coups) as a major influence, referencing it explicitly in What Time Is It There? and even featuring Léaud in his 2009 film Visage.