| Hannah Baxter |

Passenger 57 plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, April 18th, through Sunday, April 20th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org. Please blaze responsibly when attending the Trylon.

In a world where every other movie ends with a blowout fight between gods, superheroes, or both, with nothing less than the fate of the universe hanging in the balance, isn’t it refreshing when you come across a film that knows how to contain itself? Passenger 57 (1992) does. It’s the story of John Cutter (Wesley Snipes), a respected law enforcement professional who’s coaxed out of early semi-retirement to become vice president of security for Atlantic International Airlines. He’s flying out to LA to start his new job when—it’s the darndest thing!—terrorists happen to hijack the plane. Now Cutter alone can take down the terrorists and save the passengers. And he spends the rest of the 84 minutes of this compact thriller methodically doing just that.

Passenger 57 shows that the stakes are plenty high with no clash-of-civilizations tropes, Norse gods, or doomsday weapons in sight. It’s a good, old-fashioned example of what I’ll call Aristotelian action movies: films that obey the classical Aristotelian unities, and that are better for it.

The three Aristotelian unities describe a theory about what makes for good onstage drama. “Unity of action” dictates that a play should recount a single, circumscribed event without getting sidetracked by subplots. “Unity of time” means the action should take place in less than 24 hours. Finally, “unity of place” means it all needs to happen in a single location, like, say, a plane. Or an office tower. Or a bus, as we’ll see.

It’s true that Passenger 57 fudges the unities just a bit. The main plot points happen over the course of a single day, but a few scenes take place in the days leading up to the action—scenes into which the screenwriter crams exposition like luggage into the overhead compartment. Here’s Cutter’s friend Sly Delvecchio selling him on the new job:

Delvecchio: You can’t tell me that teaching security techniques to bodyguards, night watchmen, and flight attendants is something you want to do for the rest of your life.

Cutter: It’s a job, Sly. I like it.

Delvecchio: Look, Ramsey wants me to hire the best person to head up the counterterrorism unit. That person happens to be you. […]

Cutter: Damn it, Sly. Give it a rest.

Delvecchio: You give it a rest, John. This isn’t about a job, man. It’s about you. Look, nobody knows better than I do how much Lisa meant to you, but you’ve gotta stop blaming yourself. You’ve gotta get off the sidelines. You’ve gotta get back into this game!

Thanks, Delvecchio, for establishing Cutter’s credentials, tragic backstory, and internal conflict so efficiently! That evening, Cutter meditates in his bedroom, incense-wreathed and shirtless in the lotus position. We get a flashback to the convenience store robbery in which his wife was murdered, then he leaps to his feet to whale on a punching bag. The next day, he takes the job and it’s all aboard Atlantic International Airlines.

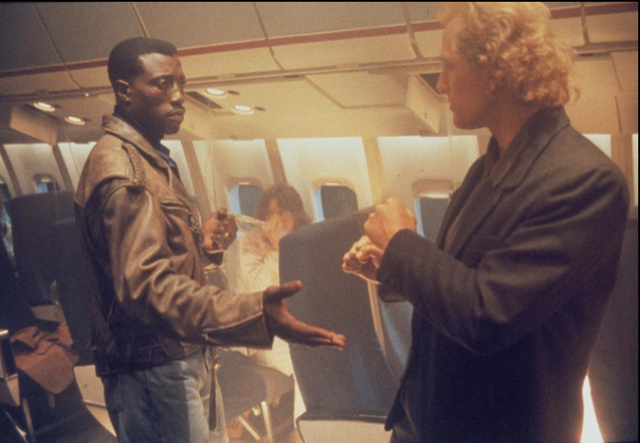

Cutter is equal to anything Rane throws at him.

Unity of place suffers slightly in Passenger 57 from a layover in Louisiana where the bad guys attempt to escape via a county fair because…reasons. I didn’t catch what those reasons were, much as I didn’t pick up on a rationale for the umpteen other hijackings boss baddie Charles Rane (Bruce Payne) has apparently perpetrated. Asked what he’s after this time around, Rane replies, “I have what I want. I have control of the plane and everything on it.” Small potatoes, maybe, but so what? It’s enough to earn Cutter’s wrath. And after all, the real reason for Rane’s campaign of terror is so we can watch Wesley Snipes take him down, just as the real reason the terrorists head to the fair is so we can watch Snipes fight them on the Ferris wheel and chase them on the merry-go-round.

Suave, ruthless, and European, Charles Rane was clearly inspired by Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman), the villain in Die Hard (1988). Actually, Passenger 57 as a whole owes much to Die Hard, the OG Aristotelian action movie. As Die Hard production designer Jackson De Govia observes in the DVD audio commentary, “Since Die Hard, everything has been ‘Die Hard on a…’ or ‘Die Hard in a…’.” (Sure enough, Entertainment Weekly titled their review of Passenger 57 “Fly Hard.”)

Die Hard is deeply committed to the unities: the action takes place almost in real time with all but a handful of scenes happening in and around the same gleaming high-rise. The building in question is the headquarters of the Nakatomi Corporation, which employs the spouse of protagonist John McClane (Bruce Willis). The corporation stores untold wealth onsite in a vault that’s considered impenetrable until Gruber and his crew come along.

Gruber strides onto the scene wearing a trench coat and a meticulously groomed beard, so you know he’s the bad guy before you hear a single utterance in Alan Rickman’s distinctive drawl. He takes a whole floor of corporate partygoers hostage and demands the release of various political prisoners, but it’s all a distraction. His true motivation—made perfectly clear to the audience, although not immediately to McClane and the cops on the ground—is greed. That’s important, because as director John McTiernan points out in the DVD commentary, the terrorists’ motivation has everything to do with the audience’s ability to relax and enjoy themselves. McTiernan says he made a crucial change to the film’s original concept by “turning the terrorist story into a robbery”:

People can have fun with a robbery. A terrorist story is by definition dark and unhappy. But with a good caper, you know, you can appreciate the bad guys too. And that allows us to put essentially some joy in the bad guys’ activity. […] Putting some joy in this story was my principal concern going into it.

Hans Gruber is a villain you can root for.

Passenger 57 finesses the motivation question in a different way. We’re introduced to Rane as he prepares to disguise himself by undergoing plastic surgery—without anesthesia, by request. He’s settling back to enjoy the procedure when a SWAT team bursts in and he decides to murder the surgeon and flee instead. It’s a change of plans, but he’s cool with it. Right away, we know we’re dealing with someone who’s driven not by political or moral convictions, but by his own twisted sense of fun. Terrorists gonna terrorize—at least until Cutter catches up with them.

Speed (1994) would have done well to hew closer to the example of Passenger 57 or Die Hard as far as its villain is concerned. Retired law enforcement officer Howard Payne (Dennis Hopper) is the baddie. He threatens to destroy a bus filled with character actors unless he gets $3.7 million dollars. It’s an oddly specific figure, up from the $3 million he seeks at the start of the movie when LAPD officers Jack Traven (Keanu Reeves) and Harry Temple (Jeff Daniels) foil his original plot to blow up an elevator. Maybe the extra $.7 million is for lost investment revenue? At any rate, Payne claims he’s only in it for the money but keeps hinting darkly at some grudge or other to do with being forced into retirement after an injury. These muddied motivational waters never become clear. Plus, Payne is not a well-heeled German heistmeister or a “sophisticated British aristocrat,” as Delvecchio describes Rane in another tell-don’t-show expository exchange. Instead, Payne’s a gray-haired retiree in a plaid button-down that your dad might feel at home in. Watching him swill Coca-Cola in his basement while he toggles between televised football and closed-circuit footage from the city bus he’s about to bomb isn’t fun. It’s scary and kind of sad.

Despite adhering nicely to the three unities (give or take a subway transfer), “Die Hard on a bus” doesn’t quite hold up the way the other two movies under consideration do, and my sense is this has a lot to do with Dennis Hopper. Compare Hopper’s Payne with Payne’s Rane (a lost stanza from My Fair Lady, perhaps?). Rane revels in being a psychopath, and in the shock and fear he inspires. He’s having a terrific time right up until Cutter throws him out the plane’s open door. Rickman—in his peerless debut in a feature film—makes the witty, cultured Gruber look like great fun at parties. McTiernan initially turned down the script for Die Hard; he didn’t say yes until the terrorists became characters you could, in his words, actually root for. Maybe it’s just me—and a Pavlovian response to Hopper cemented into my psyche by watching Blue Velvet (1986) too early in life—but I can’t see anyone rooting for Payne.

That’s why by minute 47 of my recent viewing of Speed I was already over riding the bus. No wonder people prefer light rail! Director Jan de Bont, who learned from the best as director of photography on Die Hard, must have sensed he needed a fun counterweight to the dour Hopper. You know who’s fun? Sandra Bullock. With her floral prints and her manic pixie dream girl energy, her Annie Porter charms everyone, from the bus driver to Traven and even Payne, who tries to reassure her as he straps her into a vest lined with explosives that she won’t feel a thing when they go off. Annie supplies necessary lightness–plus, her presence allows Traven to fall for somebody in lieu of actual character development. On both counts, she’s essential.

Where would we be without Sandra Bullock?

Passenger 57 does not currently enjoy the same iconic reputation as Die Hard or Speed. Maybe, though, its inclusion in the Trylon’s lineup showcasing Snipes’s magnetic screen presence will begin to rectify that. Passenger 57 is lean, mean, and Aristotelian, and it makes for a delightful palate cleanser after an installment in any of today’s sprawling action franchises, with their CGI and their baroque plots and their multiverses. A plane, an office tower, a bus–who needs a multiverse when each of these is its own little world that needs saving?

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon