| Finn Odum |

Beau Travail plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, April 6th, through Tuesday, April 8th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Author’s note: This essay contains discussions of fictional suicide and real-life suicidal ideation.

I. Citalopram

On a relatively warm Monday evening last September, while on a short walk to see Kenji Misumi’s Ken at the Trylon, I found myself struggling to cross the street.

This happened a lot that fall. I’d be on a walk (to work, the grocery store, the Trylon) when my body would freeze on the curb. Sometimes there was a light. Others, a stop sign. The street could be empty and I’d still pause. Stop and stare at the road, wondering, for a moment, what would happen if I stepped out at the wrong time. What would happen if I let myself get hit?

Just that summer, my doctor put me on Citalopram for anxiety. It worked, GAD1-wise, but I also began to sink into a numbing depression. Socializing wore me out. Rugby made me sick. Every commute made me ponder what the pavement felt like. The only reason I’d left the house that particular evening was because a friend I’d made through the theater told me he was going. The social motivation was enough that, eventually, I made it across the street and down to the Trylon.

Ken wrecked me. I wept “real bad” and would have sat there in silence for several minutes had the customer I’d forcibly befriended—legally, Kyle—not asked how I felt about it, bringing me briefly back to reality. Well after I’d gotten home, I opened Letterboxd to see what my film-adjacent friends and acquaintances thought. Some wrote about the Mishima adaptation, while others made jokes about how ripped the characters were. Kyle posted a YouTube link to the ending of Claire Denis’s 1999 film Beau Travail.

I’d never watched Beau Travail. I didn’t intend to watch Beau Travail. It was directed by a French person, and as some of my friends can tell you, I’m not a fan of those baguette-wielding freaks. But according to my local Iowa-to-Minnesota transplant, it was similar enough to Ken in themes that it warranted a public comparison. This goofy little social media post drove me to (re)assess both films for Perisphere—which is how I became enraptured by their depictions of a familiar isolation.

II. Solitude in Sword and Sand

While it pains me to credit a man who considers Decision to Leave a comfort movie, Kyle was right.2 Beau Travail and Ken are the same film. In a mere surface-level analysis, they’re both films about guys bein’ dudes—if “guys bein’ dudes” is equivalent to “men battling repression in their attempt to uphold masculinity and tradition.”

Misumi’s Ken, his only contemporary work, follows Kokubu, a student whose desire to find purpose through kendo leads to his untimely demise. Throughout the film, his leadership of the kendo club is called into question by rival Kagawa, who goes to extreme lengths to undermine him (read: tries to get him laid, because this is a movie about sexual repression, after all). Meanwhile, Kokubu has an admirer in Mibu, a first-year student who desires to emulate the stoic club leader. The relationship between the three—adversary, superior, admirer—drives the bulk of the story; even Kokubu’s interactions with literature student Eri Itami are an extension of his relationship with Kagawa, who has employed Eri to try and seduce the stoic hero.

Beau Travail inverts Ken’s character triangle. Its protagonist, Adjudant-Chef Galoup, plays the “admirer role” to his superior, Bruno Forestier, while the young Gilles Sentain is his rather one-sided “adversary.” The bulk of the film follows Galoup leading a section of the French Foreign Legion in training exercises. In between long sequences in the sun, we find Galoup obsessing over Sentain—who, unlike the combative Kagawa—has not done anything to earn Galoup’s ire. It’s his existence, his handsome demeanor, his mere likability that makes Galoup boil over. As Galoup says when he introduces Sentain, “I felt something vague and menacing take a hold of me”.

Galoup and Kokubu spend their stories entrenched in self-imposed isolation. Kokubu is alien to his peers as he roots himself in tradition and honor; he rejects modernity and represses the emotions that his cohort allows themselves to experience. Galoup, meanwhile, is insecure. He commands the Legion but feels he must compete with them for Forestier’s approval; when the younger men are hanging out in their downtime, he keeps his distance. Both men seek a version of honor they think they can only achieve through solitude—one through the sword, the other through perilous hours on the sand.

Beau Travail and Ken are littered with long training exercises that narratively amount to nothing. Not once do we see the French Legion engage in real combat, nor do we see the Kendo students in the “big competition” they are preparing for. They’re performing physicality to appear masculine and strong. But there’s no payoff. They want to exude power through the body, but by the end of each film, the body is lost. Days, hours, minutes. Sweat and blood and vomit. All for nothing.

Their only witness was the sun.

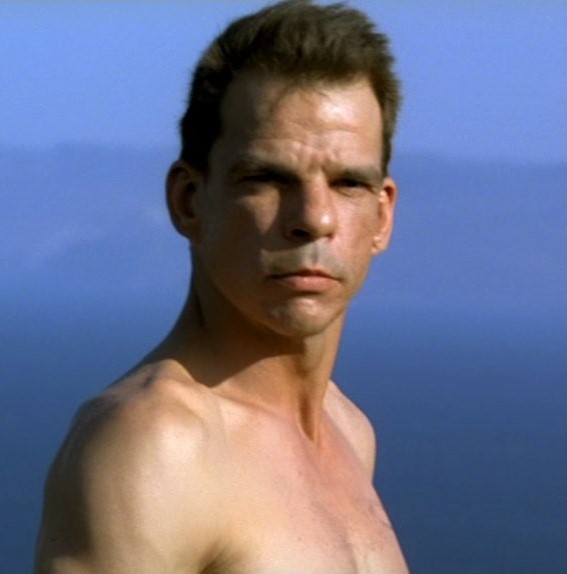

Galoup (left) and Kokubu (right)

III. The Sun

The sun looms over both Beau Travail and Ken, literally and symbolically. It lords over Galoup and Kokubu as they work their men to the bone. It’s oppressive, overbearing, sickening; late into Ken, Mibu runs from their intense kendo training to vomit into a well. The characters are often depicted as drenched in sweat from their hours of physical conditioning. Nearly every training sequence in Beau Travail takes place in the daylight, the men stretching, fighting, and lying in sun-scorched sand. It’s exhausting, the heat driving them to train and in turn making them ill, insecure, isolated.

It’s a solar bottle of Citalopram.

The sun radiates throughout the color schemes of both films. Ken is shot in a high-contrast black and white, where the shadows are ink-black and the sunlight is sharp. The film opens on a scene where a much younger Kokubu is staring up into the sky as his older self narrates how he was enraptured by the sun’s “spark of pure life.” Even in greyscale, the sun is vibrant, a scalding hole in the sky that draws attention away from the rest of the frame. Meanwhile, Beau Travail is riddled with color—primarily the deep blues of the ocean matched against tawny sand and stone. Sunlight illuminates the water into a crystalline blue-green. It’s too bright. The audience is immersed in the heat that the Legion is training under—in fact, the only time they’re depicted as not training is when they’re in the dark. The sun, through its brightness and vibrancy, oversees their suffering. I could feel that sunlight in the theater, in my living room. It burned.

In Ken, the sun symbolizes Kokubu’s isolation. As Kokubu seeks out the sun’s “spark of life”—power, strength, whatever you want to call it—he distances himself from his peers. His subordinates begin to view him as the solar body—to a classmate, Mibu says that Kokubu is “far too bright to face, just like the sun.” Bright, powerful, strong—but too hot, too far away, hard to reach, and dangerous to touch. The film’s turning point sees Kagawa leading the kendo students to the ocean in an attempt to cool off from the sun’s heat; Kokubu sees this as a sign of his failure. He wasn’t strong enough to lead him. In one of his final moments, he’s seen speaking to Mibu, partially obscured in shadow. The sun has gone down.

The last time we see him, the sun rises over his dead body.

Beau Travail’s sun is somewhat less metaphorical: Galoup’s final spiral begins with a subordinate overheating during a punishment. Our protagonist has set a trap for Sentain, using another man’s sun-induced suffering to draw in the empathetic soldier. Galoup punishes Sentain for “obeying an order” and strands him in the hot, arid desert without a working compass. The sun is his weapon, its heat designed to kill. But it backfires, as Sentain’s compass is found and Forestier assumes Galoup tried to kill the young man. He’s stripped of his command and sent back to France. Everything he worked for, gone in an instant.

The sun goes down. But for Galoup, there is freedom in the shadows: his final scene is set in the nightclub his soldiers frequent throughout the film. Totally alone, he begins to dance, letting loose everything he’d locked inside of him. He’s lost everything he worked for—but perhaps he’s finally free.

IV. The Rhythm of the Night

When you deal with trauma, art that is any bit reminiscent of your pain can be like reliving a car crash. Ken struck me in a moment of weakness. I saw myself in Kokubu’s desperate grasp at “tradition” and “honor.” I was failing at the few things I was good at—and if I couldn’t even be good at leading, at writing, at working the counter of a theater for three hours on Sunday, then what was the point? Galoup, with his insecure rage and self-induced isolation, dug further into that wound. He needed to belong—the same way that I so violently wished to—but could not accept himself, who he could’ve been, and created his own destruction.

If I wanted, I could self-destruct too. I could self-isolate, I could resent, I could stew in my inner turmoil until that ideation became concrete. Like Galoup, like Kokubu, like all their subordinates, the sun beat down on me. The difference was that I could sit in the shade.

When the cold of winter rolled in last December, I stopped taking Citalopram under my therapist’s guidance. We were well underway with EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) and anxiety-management strategies. I started to open up to my loved ones about the thoughts I’d been having. I kept watching movies. I committed to this essay, got Kyle’s consent to credit him with the inspiration,3 and didn’t realize that upon rewatching, these movies would burrow into my heart as much as they did. I guess I owe him an apology or something for not entirely committing to the “these are the same movie about repression” bit. I think he’ll live.

So will I.

Footnotes

1 Generalized Anxiety Disorder 🤪

2 I cannot talk too much shit because I will rewatch the original Saw when I need a pick-me-up…but come on, man!

3 If you’re inclined, you can follow him on Letterboxd. You can also follow me on Letterboxd, but that’s neither here nor there.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

So — I just finished reading a novel by Val McDermid that referenced EMDR. I haven’t watched either film so no comments on your well-written comparison. Just a note that where I recognized you as I was driving by, I was drawn to your sense of joy and confidence. If you were not skipping, I certainly thought you were.