| David Potvin |

Magnolia plays on glorious 35mm from Friday, March 7th, through Tuesday, March 11th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s 1999 magnum opus Magnolia is sonically chaotic. There’s no two ways about it. Within the first eleven minutes we meet no less than nine members of the film’s ensemble cast amidst a cacophony of these characters’ morning routines. Aimee Mann’s rendition of “One” is playing, vocals and all, but we are hard-pressed to discern much of the lyrics. Weaving above and below the song in the sound mix we hear television commercials and programs, multiple households of barking dogs, a car stereo playing an entirely different song, said car crashing into a convenience store, and a voice message from a dating phone service. Audio-wise, the film does not let up much from there. In addition to other songs by Mann there is a resounding score of intense, moody strings composed for the film by Jon Brion. The music holds things together as we’re tossed from one part of the San Fernando Valley to another, character to character, witnessing their various personal tragedies unfolding. It is emotionally draining, to say the least.

Then, 139 minutes into the film, something unexpected happens. We hear the opening piano notes to Mann’s song “Wise Up.” They sound almost hopeful. Sure, we see Claudia Wilson Gator (played by Melora Walters) snort a couple lines of cocaine, but she’s at home, seated, with candles lit. All is calm compared to the trials we’ve seen transpire so far. We hear Mann’s vocals begin. In the next moment, Claudia is singing along. We know she listens to music at home because police officer Jim Kurring (John C. Reilly) had asked her to turn it down in a previous scene. The camera is moving slowly towards Claudia as she sings. Something different is happening here.

The camera cuts and we now hear a man singing. It’s Officer Jim seated on his bed in his home. We’re forced to ask ourselves: is this music coming from a diegetic source? Is this song playing on the radio and both characters happen to be listening to it at the same time? We cut again; this time we’re in the home of Jimmy Gator (Philip Baker Hall), Claudia’s father and television quiz show host, who sings along in a raspy, near-whisper. It seems less likely that the song is actually playing in the room there with him too. That would mean, like the film’s score, this song is non-diegetic; it exists outside of the reality of the film. And yet, all these characters are interacting with it.

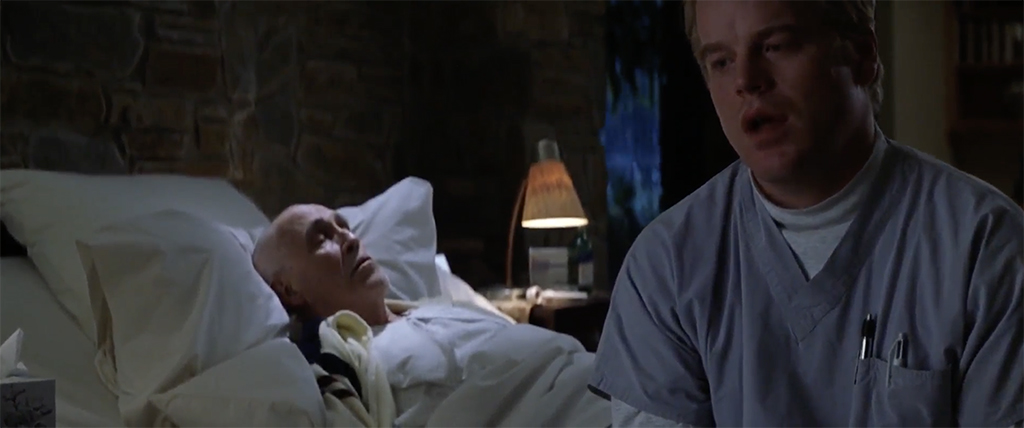

There’s also Donnie Smith (William H. Macy), a washed-up former “quiz kid” singing in front of an oversized check mounted on his wall. Then, in case we had any remaining doubts, the camera cuts to a dying and bedridden Earl Partridge (Jason Robards) and his hospice nurse Phil Parma (Philip Seymour Hoffman). Earl is heavily sedated and struggles to string a sentence together. He has transcended his frailty and physical limitations, however, to join the chorus. What was initially plausible has now become fantastical. We see Earl’s wife Linda Partridge (Julianne Moore) and son Frank T.J. Mackey (Tom Cruise) singing in their respective cars. Finally, current quiz show wunderkind Stanley Spector (Jeremy Blackman) pipes out the last lyrics from a darkened library (“so just… give up”). For a first-time viewer, this sequence is both baffling and magical. There’s relief to be found in experiencing it.

For me, Magnolia is physically felt. As the drama unfolds, as the characters wallow and are tossed about treacherously by their unprocessed traumas, I feel a pit forming in my stomach, a lump in my throat, an ache towards the front of my head and behind my eyes, a pressure in my sinuses. As “Wise Up” fades out, however, I find those sensations lifted. The threads of the story, intertwined and pulled ever tighter, loosen up.

In his book Transcendental Style in Film, Paul Schrader mentions the shots, essentially b-roll, that director Yasujirō Ozu would use after scenes of conflict. Schrader calls these shots “‘codas’: still-life scenes of… empty streets and alleys, a passing train or boat, a distant mountain or lake.”1 We often take these moments for granted when we see them in films or television, but their presence holds a specific function: they offer us time to digest what we’ve just seen or to reset our minds before being shown more. Anderson largely denies us these moments in Magnolia, and the effect is that we’re desperate for a breather by the time the cast performs their mid-film sing-along.

Many other films feature an ensemble singing a song across multiple locations. Most of these arguably fall within the musical film genre, where characters recurringly break into song throughout the film. “Wise Up” is the only instance in Magnolia where characters sing. It’s a one-off, an anomaly. We’ve seen more recent instances of non-musical films co-opting musical film conventions: Step Brothers (2008) and 500 Days of Summer (2009), for instance. Most often, though, the inclusion of musical numbers is played for laughs. The filmmakers lean into the spectacle with choreography, daydream sequences, and so on. What happens in Magnolia is something else: singing as emotional expression, laid bare.

The sing-along is only the second-most surprising thing to happen in the film. (For those who haven’t seen Magnolia yet, I’ll leave things amphibious—er, ambiguous, rather.) Still, to see the sequence in context for the first time is dumbfounding. As far as the diegesis of the film goes, it’s nonsense. We’re not sure it should exist. And yet, for that moment, it’s everything we need.

Footnote

1 Paul Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (University of California Press, 2018), 57.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon