| Dan Howard |

Eyes Wide Shut plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, January 17th through Sunday, January 19th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

There’s certainly something about the holiday season that strikes a chord with filmmakers. Whether it’s Todd Hayne’s Carol, Tim Burton’s Batman Returns, or Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, any film using Christmas as the backdrop for a non-holiday story sets a specific type of melancholic atmosphere that can feel more accurate around the holiday season for some people, and perhaps these stories even help give the kind of escape we look for around this time of year. For Stanley Kubrick, this sentiment is undoubtedly right up his alley. However, I’ve always been curious why Kubrick chose this particular type of lonely yuletide tale and reimagined it through an unsettling, psychosexual lens.

Eyes Wide Shut follows married couple Dr. Bill (Tom Cruise) and Alice Harford (Nicole Kidman) over a two-day period that starts with a Christmas party hosted by one of Bill’s wealthy patients, Victor Zeigler (Sydney Pollack) where Bill also runs into a former classmate of his, Nick Nightingale (Todd Field). Later that night, Alice reveals to Bill a sexual fantasy she had about a naval officer she saw during their vacation to Cape Cod the summer before. Unable to get the images of his wife and the officer out of his head, Bill sees Nick again and discovers a secret party through him. Bill arrives at the remote location of the party to discover a mass masked orgy. When Bill is discovered by the party and is threatened by the masked participants when they throw him out, Bill fears for the safety of himself and his family through the hours that follow.

The decision for the Christmas setting seems a bit unusual since Kubrick rarely touched on religion. When writing the film, Kubrick had many meetings with his co-screenwriter, Frederic Raphael, and discussed the original novella, Traumnovelle (aka Dream Story). Raphael had fought for the Jewish identities of Cruise’s and Kidman’s characters since the novella’s author, Arthur Schnitzler, was Jewish himself. Though Kubrick never seemed to be ashamed of his own Jewish background, he wanted no Jewish characters in the film. Yet, despite Kubrick stubbornly arguing against it, Raphael essentially got his wish when the great Sydney Pollack replaced Harvey Keitel, who had quit due to Kubrick’s high demands, for the character of Ziegler. It would make sense, though, if Kubrick simply didn’t see a reason how religion would, in any way, serve the story and drive it forward. After all, you never really get a sense of any character’s identity as it is, such as religion or differing cultures, when you watch The Shining, 2001: A Space Odyssey, or Full Metal Jacket as he seems to prefer to focus on the bigger picture of his works. Yet, the Jewish influence of the novella remains ever-present.

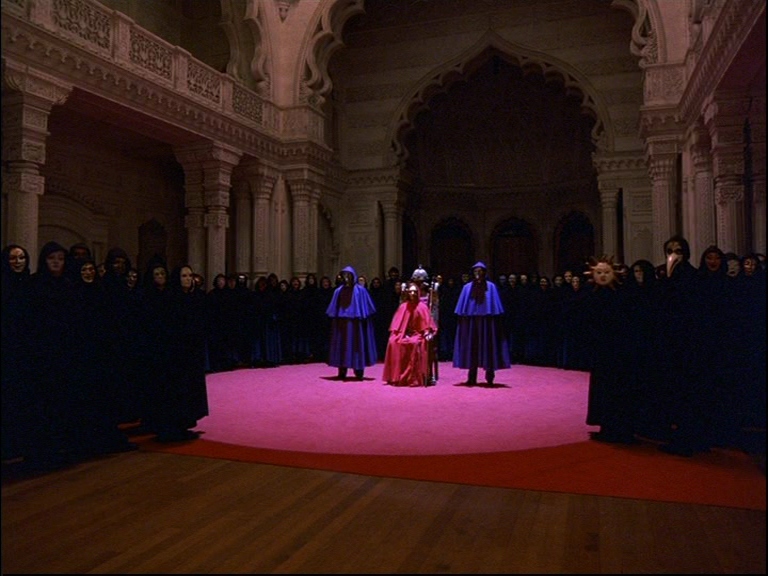

This conflict of identity begs the question of why this story and why at Christmas? Whether you celebrate it or not, Christmas is pushed on practically everyone. Perhaps that’s why Kubrick chose to set Bill and Alice’s sexual odyssey during that time. It’s a stressful time of the year for so many and that stress can unintentionally lead to the kind of argument Bill and Alice have after the party. While sharing a joint to relax, Alice tells Bill someone tried to sleep with her earlier that night. Bill responds in a passive manner, and she becomes distraught. The fight leads to Alice revealing the sexual fantasies she imagined about a Naval officer she had spotted during their Cape Cod trip the summer before. How even though Bill was as “tender and loving as ever,” she would have given up her whole life for one night with the officer. The revelation plagues Bill’s mind with images of any possible sex acts between his wife and this mystery man. Seeing Bill face his own temptations throughout the night, we get a glimpse into his mental anguish as the various moral conflicts he feels with every encounter leading up to his arrival at the mansion where the orgy is held, and his emotions shift from inadequacy to fear when he’s discovered and forced remove his mask.

Paranoia seems to have just as much a connection to Christmas for Kubrick as sex. Bill is threatened to never speak of what he’s seen or else he will suffer consequences, which leaves him moving through the next day in a highly paranoid state. Feelings of being followed and/or watched are at the forefront of his mind as much as the thoughts of the naval officer and Alice. Even the newspaper Bill reads has the “Lucky to be alive” headline in full view. There’s a further link between sex and paranoia when Bill ultimately gets discovered as an outsider and is forced to unmask in front of the mysterious group, his expression gives the impression he’s exposing more than just his face. When all eyes are on you, there are times when it feels like the very essence of your being is on display. Bill’s insecurities and deepest fears seem like they’re being read by every set of eyes in the room. Being unmasked seems to be where his paranoia begins. Do the holidays always make people feel rather paranoid, though? Perhaps they’re worried about not getting the right gifts or clashing with someone in their family or otherwise that might ruin their Christmas for them. For Bill, it’s fearing for his life and the possibility of his wife and child being harmed because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. A bit on the extreme side, sure, but it would fit in with the intensity of a story like Eyes Wide Shut and could very well open up the imagination as to why Kubrick chose to associate this story with Christmas.

Kubrick’s disturbingly astounding final masterpiece makes for an unforgettable experience and the perfect unconventional Christmas film. However, even with all the heaviness, unease, and his signature tone in Eyes Wide Shut, was this truly the vision Kubrick would’ve been happy with in the end? Kubrick was notorious for changing his films even after their theatrical debut. 2001: A Space Odyssey, for instance, was pulled from theaters shortly after. Kubrick decided to cut 17 minutes out of the original film. While Kubrick had presented a first cut of Eyes Wide Shut to the producers, he was still working on the film’s edit even up to his death in 1999. Since Kubrick never lived to see the release of Eyes Wide Shut, we must assume that most of the film is what Kubrick was satisfied with. Although, I have no doubt that he would’ve had something to say about Warner Bros. digitally altering the main orgy scene, adding shadowy figures to obscure certain sex acts depicted on screen. While that does ultimately add some ominous nature to that scene altogether, Kubrick was never one to take censorship lying down. Whether it is truly the movie Kubrick wanted us to see, we’re still happy we got one more from the master before his departure. While the connections Kubrick made between Christmas, sex, and paranoia are ever present, any definitive meaning behind them is best left for interpretation, leaving the mystery open-ended. I’d like to think that’s how Kubrick would’ve wanted it for his audience. As Alice says to Bill, “The reality of one night, let alone that of a whole lifetime, can never be the whole truth.” To which Bill responds, “And no dream is ever just a dream.” With the legacy Kubrick has, including this fever-dream-like Christmas tale, what a dream for him to leave behind for the world.

Edited by Finn Odum