| J.R. Jones |

Lenny plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, January 12th, through Tuesday, January 14th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

There’s obscene, and there’s obscene. When standup comedian Lenny Bruce, worn down by years of prosecution for narcotics possession and obscene language in his nightclub act, died of a morphine overdose in August 1966, police gave news photographers a five-hour window to snap pictures of him, lying naked on the bathroom floor of his house in the Hollywood Hills.1 The public lesson of this exercise couldn’t have been clearer—not just “this is what happens when you do drugs, boys and girls” but “this is what happens when you stand onstage ridiculing organized religion, condemning racial segregation, and trying to normalize filthy language and homosexual acts.”

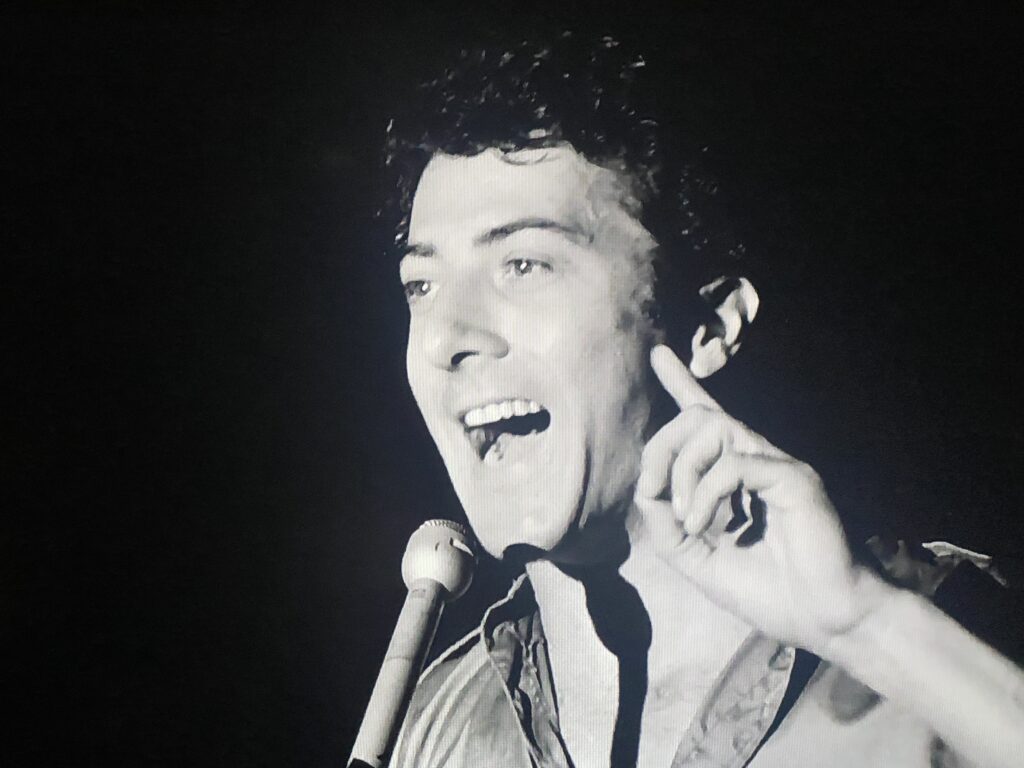

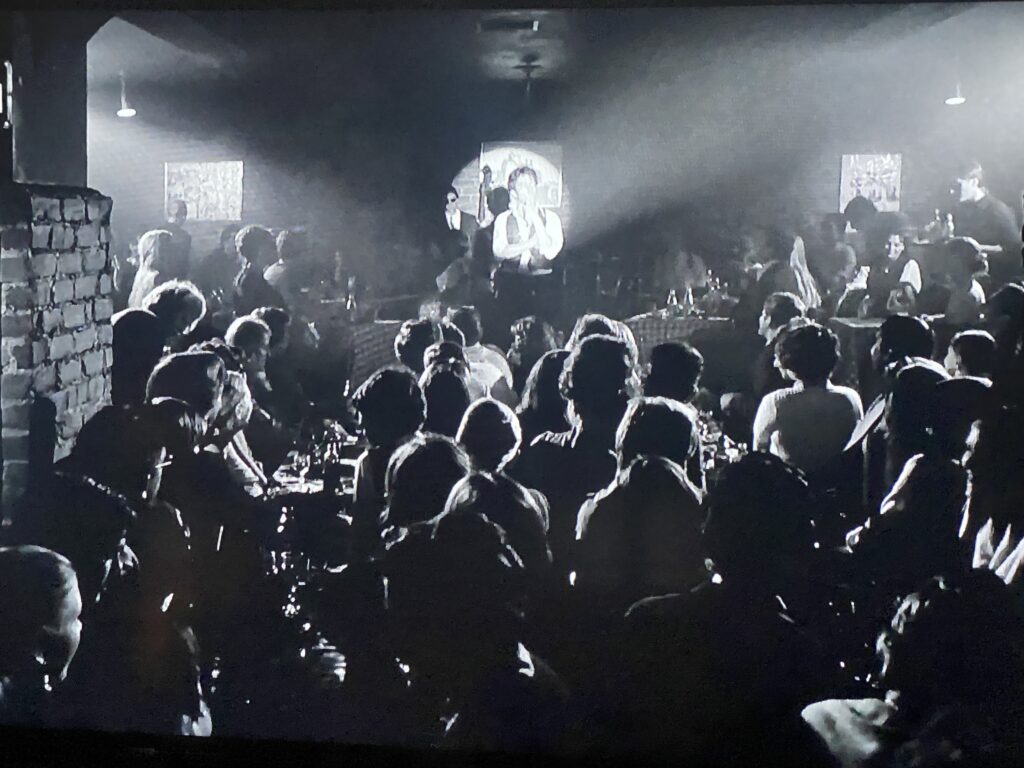

Less than a decade later, Bob Fosse ended his black-and-white biopic Lenny (1974) with a re-creation of that final photo shoot, zooming out slowly on an image of Bruce (in the person of Dustin Hoffman) flat on his back. By then Bruce had been deified as a martyr for free speech. In this context, the closing image feels like a beatification. Nominated for seven Oscars, Lenny has been the popular shorthand for this eccentric, brilliant, subversive comic ever since (or at least until he was fictionalized for The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel). But Lenny isn’t a funny movie. Drawing heavily on the testimony of Bruce’s ex-wife, Honey, it gives us Lenny the lover, Lenny the lecher, Lenny the addict, Lenny the crusader, Lenny the victim. What it never manages to deliver is Lenny Bruce the comedian.

Curious? Check out his 107-minute concert at Carnegie Hall in February 1961, recorded at midnight to a sold-out house after a snowstorm had all but immobilized New York City. Or track down the 6-CD set Lenny Bruce: Let the Buyer Beware, a cornucopia of complete nightclub performances, TV and radio spots, and personal recordings. They reveal a lightning-quick mind taking a scalpel to public mores but also a seasoned entertainer hungry for laughs, a strip club veteran who provoked his audiences with taboo subjects even as he parodied old movies and did impressions of Bela Lugosi.

Bruce’s humor can take some deciphering because his speech was so thick with Yiddish and hipster slang, rendered even less intelligible at times by his tumbling, hyperactive delivery. The liner notes for Let the Buyer Beware include an extensive glossary of Yiddish words that pop up in his shtick (including shtick). Bruce was well aware of the communication problem: during the Carnegie Hall show, he imagines two guys in the audience trying to sort through his jargon, until the whole show turns into a big game of What’s-It-Mean. “The most erudite guy, all I have to do is hit one word that’ll send him off,” Bruce laments. “‘What does “bread” mean? What’s “putz” mean? What’s that mean?’ And then he just missed the whole up-bup-BUP! And I lost him!”

With or without a glossary, Bruce was a spellbinding vocal performer with a dramatist’s sense of dynamics. A jazz buff, he had a voice like a trumpet and loved to use it, yet he delivered some of his best punch lines in a hushed whisper. His pauses were masterful; even on recordings one can imagine him looking around the room as the tension builds, waiting to unleash the zinger. Well-polished routines such as “The White Collar Drunk” or “Religions, Inc.” might veer off into stream of consciousness as he introduced a funny idea and tried to shape it into a bit. At Carnegie Hall one routine is interrupted by howling feedback from his stage microphone, but he uses it to conjure up an image of vampire bats hovering above the audience and waiting to strike.

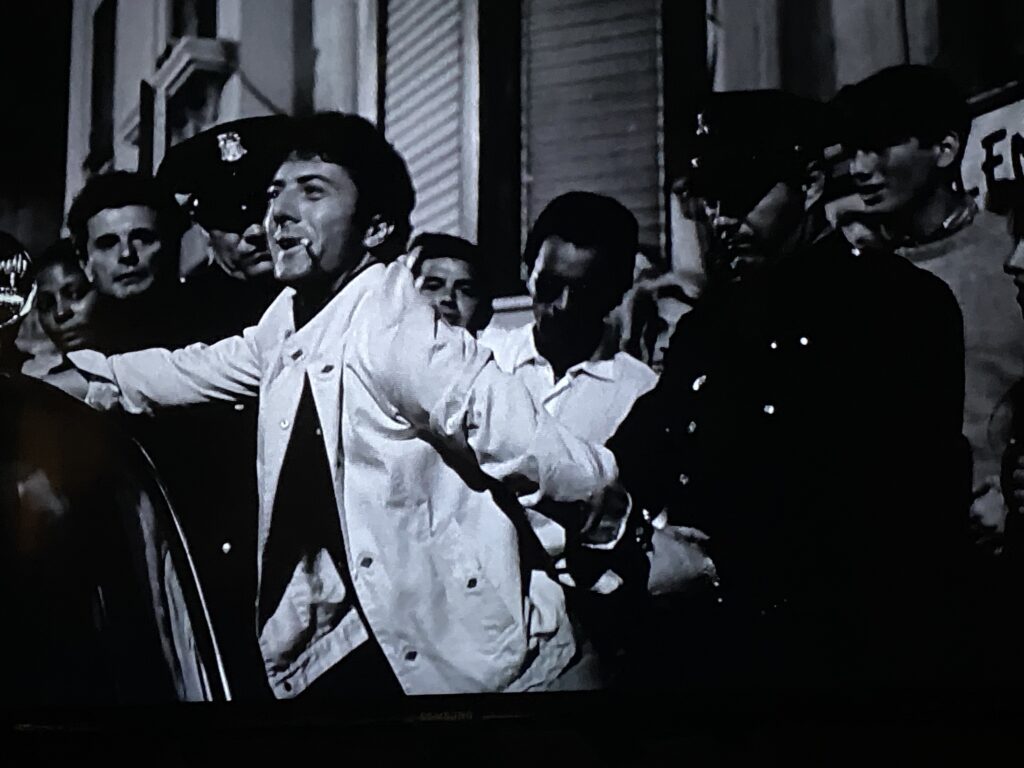

Lenny Bruce is arrested for obscenity after a performance at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco, Oct. 4, 1961. San Francisco Examiner press photo, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fosse adapted Lenny from a successful Broadway play by Julian Barry, who is credited as screenwriter, but the true storyteller is Honey Bruce, the comedian’s wife from 1951 to 1955 and a consultant on the film. She was stripping under the name “Hot Honey’ Harlowe when she met Lenny; according to the film, their relationship was wrecked by a showbiz lifestyle that encompassed heroin addiction and Lenny’s appetite for sexual experimentation. Lenny is, first and foremost, a love story from Honey’s perspective: Fosse opens with a close-up of her lips (in the person of Valerie Perrine) as she waits for the first question from an off-screen interviewer, and as soon as the opening credits are out of the way, there’s a two-and-a-half-minute sequence of her taking it all off for a late-night crowd of drooling men. Honey takes possession of the narrative so completely that the movie’s original tagline was “Lenny said it. ‘Hot Honey’ did it. Together they shocked America.”

Bruce’s comedy takes a back seat to the troubled marriage and, later, his prosecutions for using the word “cocksucking” in a San Francisco nightclub in October 1961 and for allegedly violating obscenity laws in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City (he was pardoned in New York in 2003). There are numerous scenes of Hoffman re-creating Bruce’s nightclub act, but they’re mostly snippets, inserted into the romance as commentary; Fosse doesn’t spend any serious time onstage with Bruce until the bitter end, when he’s reading from the transcripts of his court cases and patrons are walking out on him. The longest scene of Bruce performing is an excruciating sequence, late in his disintegration, in which he comes onstage wearing only a raincoat, strung out and rambling incoherently.

Hoffman has complained that Fosse raced him through the nightclub sequences,2 which can be fatal for comedy. Most of the Yiddish has been scrubbed away to make Bruce more comprehensible to goyish moviegoers. But Hoffman makes little attempt to reproduce the comedian’s distinctive vocal style or timbre; the words are there, but not the music. “Please don’t applaud,” Bruce used to tell audiences. “It breaks my rhythm.” By contrast, when Hoffman’s Bruce wins a standing O, he protests but basks in the applause, grinning from ear to ear. That sense of sanctimony may be the film’s most obnoxious aspect. Lenny Bruce was always quick to note his own hypocrisy, his own culpability in the ills he denounced. He liked to stress certain points by snapping his fingers, but Hoffman always seems to be shaking his.

In one of his last performances, Bruce rued the fact that he was often judged on someone else’s performance of his words:

I do my act at, perhaps, eleven o’clock at night; little do I know that at 11 A.M. the next morning, before the grand jury somewhere, there’s another guy doing my act who’s introduced as Lenny Bruce in substance. “Here he is; Lenny Bruce in substance.” A police officer … does the act. The grand jury watches him work, and they go, ‘That stinks!’ But I get busted. And the irony is that I have to go to court and defend his act.”3

That may be the best one-line review of Hoffman’s performance: it’s Lenny Bruce in substance. So is Luke Kirby in The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, though he comes closer to replicating Bruce’s sly delivery and sardonic charm. Playing Lenny Bruce is a vocal challenge equivalent to Austin Butler singing the songs of Elvis Presley or Timothy Chalamet of Bob Dylan, because standup comedy is a thing of the stage, of style as well as substance. Lenny recounts the downfall of a great comedian, but because its comedy is less-than-great, Bruce comes off as just a drugged-out shmuck who got screwed by the system. “Into the shit-house for good this time,” he mutters in voice-over as Fosse pulls back on the body. Lenny Bruce deserved better then, and he deserves better now.

- Ronald K.L. Collins and David M. Skover, The Trials of Lenny Bruce: The Fall and Rise of an American Icon(Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks MediaFusion, 2002), 339. ↩︎

- Patrick Agan, Hoffman vs. Hoffman: The Actor and the Man (London: Robert Hale, 1986), 67, 69, 70; in Ronald K.L. Collins and David M. Skover, The Trials of Lenny Bruce: The Fall and Rise of an American Icon (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks MediaFusion, 2002), 397. ↩︎

- The Lenny Bruce Performance Film (Santa Monica, CA: Rhino Home Video, 1992). The performance took place in August 1965. ↩︎

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon