| Andrew Neill |

An Autumn Afternoon plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, December 27th, through Sunday, December 29th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Let’s get a potentially uncool but nonetheless true thing about me out of the way right now: I am a huge fan of the American film director Wesley Wales Anderson. You probably know him as Wes Anderson. He’s one of my favorite directors—gotta be in the top three, no question. And if you haven’t already clicked/tapped “Close Tab” from secondhand embarrassment and made it to this sentence, you’re one of the real ones. You understand that saying you’re a huge Wes Anderson fan in a mixed company of cinephiles is a third rail within our passionate community, but we’re here and we need not hide, my friend. I’m Mr. Fox raising my fist into the air, and you’re the lone wolf on the hill raising yours in solidarity. Welcome. You’re safe here.

Anderson is a gateway director. His style is so overt and identifiable that his work can be shown to budding film enthusiasts as an easy example of auteur cinema. But his work also opens doors to a host of influences across film history. Part of the joy of watching his films is how each one wears its influences on its sleeve so proudly. We fans then seek out these precursors to deepen our film knowledge and appreciation.

Amongst Anderson’s key influences, with their immaculate craft hiding messy emotions, are the works of Japanese master director Yasujirō Ozu. As the Trylon’s “Yasujirō Ozu in Color” series plays this month, let’s seize the opportunity to connect Ozu’s work to Anderson’s. We’re going to look at two films in particular: Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon from 1962 and Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums from 2001—two films centering families with complex or outright dysfunctional dynamics who inhabit intricately designed spaces. Both films support themes of loneliness, disillusionment, and unspoken feelings. I’m calling it “The Architecture of Family” because it sounds cool. Thanks for indulging me. Let’s dig in.

Family drama is at the front and center of these films, and at the front and center of the drama is a patriarch: Shuhei Hirayama and the titular Royal Tenenbaum. Shuhei is a middle-class businessman, widower, and father of three adult children. He’s facing pressure from all around to marry off his 24-year-old daughter Michiko, who lives at home and cares for him and his youngest son, Kazu. Royal, on the other hand, is a disbarred lawyer and estranged father of three adults who were each celebrated as geniuses as children, but have fallen into grief and obscurity. He’s facing bankruptcy and eviction, which inspires him to reconnect with his family.

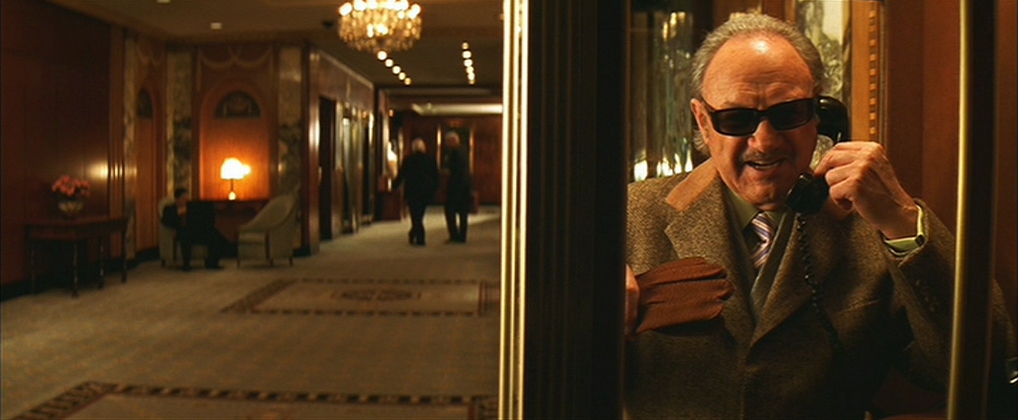

The characters of these two men couldn’t be further afield. Shuhei is respected personally and professionally and present at home. He was the captain of a Japanese destroyer during World War II. When he stumbles into a former crewmember, the man greets him enthusiastically and invites him out for drinks. Whereas Royal is perhaps best described as he’s described in the film: a real “sonuvabitch.” He’s a blowhard and a con man who pretends to be dying to ingratiate himself back into his distanced family.

The conflict for Shuhei seeps in from outside forces, particularly in the form of pervasive cultural norms. While at the start of the film Shuhei says there’s no rush for his daughter to marry, his peers urge him otherwise, claiming all the desirable suitors will be taken. To add to his anxiety, Shuhei reconnects with an old friend—inexplicably nicknamed “The Gourd”—who operates a noodle shop in a bombed-out part of the city, whose situation offers a glimpse into a possible dark future. The Gourd is also a widower and refused to marry off his daughter for fear of loneliness, only to embitter their relationship and become a drunk. Michiko ultimately marries—though in a choice betraying the union’s impersonal nature, we never see her husband—and the film ends with Shuhei sitting alone in his dark kitchen.

The conflict for Royal and the Tenenbaum children comes from within, involving long held secrets, insecurities, and betrayal. Royal profited from his son Chaz’s business dealings while Chaz was a minor, forcing Chaz to arrest control from him later in life. Royal continually held his adopted daughter Margot at a distance, introducing her as “his adopted daughter” and leaving her out of family functions. The only kid Royal took a shine to was Richie, whose skill and success as a professional tennis player came off as having the most value, not least because he would gamble on Richie’s matches.

Same frame, different day. Ozu captures Shuhei from a similar angle, but in a far different mood.

The spaces that Ozu and Anderson create and populate with all these characters and their dramas contribute significantly to the storytelling. Both directors are fastidious about everything that appears in frame. If it’s in there, it’s contributing something to the story. However, their approaches to achieving similar aims vary dramatically. Comparing the frames of Ozu and Anderson tells a tale of minimalism versus maximalism.

Ozu is the minimalist. An Autumn Afternoon takes place primarily in a few recurring locations, like Shuhei’s office, the Hirayama family home, or a private room in a favorite restaurant. In each location, Ozu blocks the actors in similar positions and uses repetitive framing from scene to scene. This use of repetition invites the audience to pay closer attention to the characters, who are often communicating their truth nonverbally or in direct opposition to what they’re actually saying. To get metaphorical, Ozu constructs scenes out of Legos. He reuses cinematic building blocks from scene to scene, drawing the audience’s attention to subtle differences that further develop his narrative. Changes in behavior are put into relief against familiar backdrops, and if something in the room has changed, we’re left to wonder why.

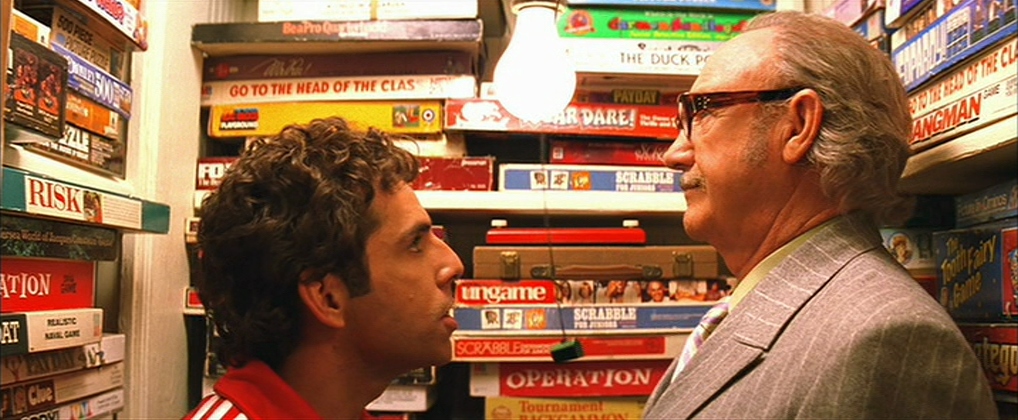

If Ozu is constructing minimalist Lego sets, Anderson is designing maximalist dollhouses, and the Archer Avenue house in The Royal Tenenbaums is one of his greatest constructions. Aside from Royal, most members of the Tenenbaum family keep their feelings bottled, which leaves room for the spaces they inhabit to speak for them. Anderson packs the frame around them with details, so much so that it’s impossible to catch everything even after many viewings. Richie’s paintings cover a ballroom wall, all of which feature Margot’s stoic stare. Margot locks herself in a dingy, tiled bathroom, with the smallest television ever tied to an old radiator. Chaz and Royal have an argument in a tight closet brimming chaotically with colorful board game boxes. Bright pink or red painted walls throughout the house hint at a past joy and vibrancy that the characters are unable to accept in their current, dysfunctional state.

While the immaculately designed spaces leave openings for interpretation, some of us have a dang piece to write and aren’t allowed such ambiguities! Let’s lay out the common themes between An Autumn Afternoon and The Royal Tenenbaums, starting with loneliness. Royal lies to his family about dying so he can live with them rent free, but their presence puts into perspective how lonely his life has been, coaxing him to act more genuinely and earn their affection. Shuhei is enjoying life with Michiko at home, and she isn’t in any rush to leave, until societal pressure pushes them apart. As The Gourd says in a drunken stupor, “In the end, we spend our lives alone… all alone.” Shusei fears the loneliness that The Gourd is living in, but by marrying off Michiko, he ends up creating his own version.

Unspoken feelings and unrealized potential permeate both films. Michiko ends up marrying an unseen rando rather than Miura, the man she truly yearns for, because her father and brother told him she wasn’t ready and he moved on. Margot’s marriage to psychologist Raleigh St. Clair drove her into a creative stall and drove her brother Richie into an emotional spiral that ended his professional tennis career. Richie and Margot share a mutual desire, but the taboo of their being siblings, although not by blood, forces them to “be secretly in love with each other and leave it at that.”

Michiko and Richie feel blue in the face of unrequited love.

The theme of disillusionment is represented by the eldest brothers of both films. Koichi Hariyama is married to wife Akiko, but doesn’t seem to find much fulfillment in it. He tries to fill the void by purchasing used golf clubs with money he borrows from his father for a new refrigerator. He celebrates a minor victory when Akiko approves of his purchase, as long as she can put some of the money toward a new handbag. They at least have materialism in common. For Chaz Tenenbaum, his love for business is outshined by his love for wife, Rachael, and their two boys, Ari and Uzi. But after a tragic plane crash claims Rachael’s life, Chaz develops an obsession for safety and moves himself and his boys back into his childhood home, less for actual security purposes and more as a familiar “security blanket.”

There’s so much more to dig into between Anderson and Ozu. One delightful detail I won’t cover extensively, but rewards further exploration of their respective catalogs, is their use of a stock company of players. Both directors work with the same performers again and again. Chishȗ Ryȗ, who plays Shuhei in An Autumn Afternoon, is essentially Ozu’s Bill Murray. The guy is in so many of his films, and for good reason; he’s such a warm, inviting presence. Ozu’s oeuvre in general rewards the keen observer. In addition to the casts, the narratives and settings bear a strong commonality from one to the next, iterating on themes of family, modernization, and cultural norms. For Anderson fans, I recommend Good Morning—which also recently screened as part of the Trylon’s Ozu series—as a great next step. It’s a much more comedic turn for Ozu, including some killer fart jokes! Anderson fandom offers a glimpse into a host of deeper cinematic worlds like Ozu’s, if you’re willing to take a closer look at the scenery.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

If loving Wes Anderson is uncool, then dress me in socks, sandals, hiked up overalls, and my teenage headgear and smack a kick me sign on my back.