| MH Rowe |

On Dangerous Ground plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, December 15th, through Tuesday, December 17th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

On Dangerous Ground (1951) might appear at first to be one of the more unbearably melodramatic film noirs ever produced. Its ending, or really the ending of the ending—the film’s final scene—threatens especially to pull all that has preceded it down into the depths of pure sap, like the flotsam and jetsam from a sentimentally scuttled ship. But I have a fondness for melodrama in film, especially if the melodrama attains a certain oneiric high of wild feeling. On Dangerous Ground is the dream of a desolate bad cop.

Directed by Nicholas Ray and starring Robert Ryan and Ida Lupino (who, though uncredited, directed some scenes during production), the film starts with a simple typology of police detectives. There exist only two types here, and we grasp their essential nature watching them get ready for their evening shift. The first type of cop comprises Pop Daley (Charles Kemper) and Pete Santos (Anthony Ross), the colleagues of Jim Wilson (Robert Ryan). Daley and Santos have worried wives and/or children. They get hugged while strapping on their guns. They leave behind their favorite chair and a brood of kids watching TV.

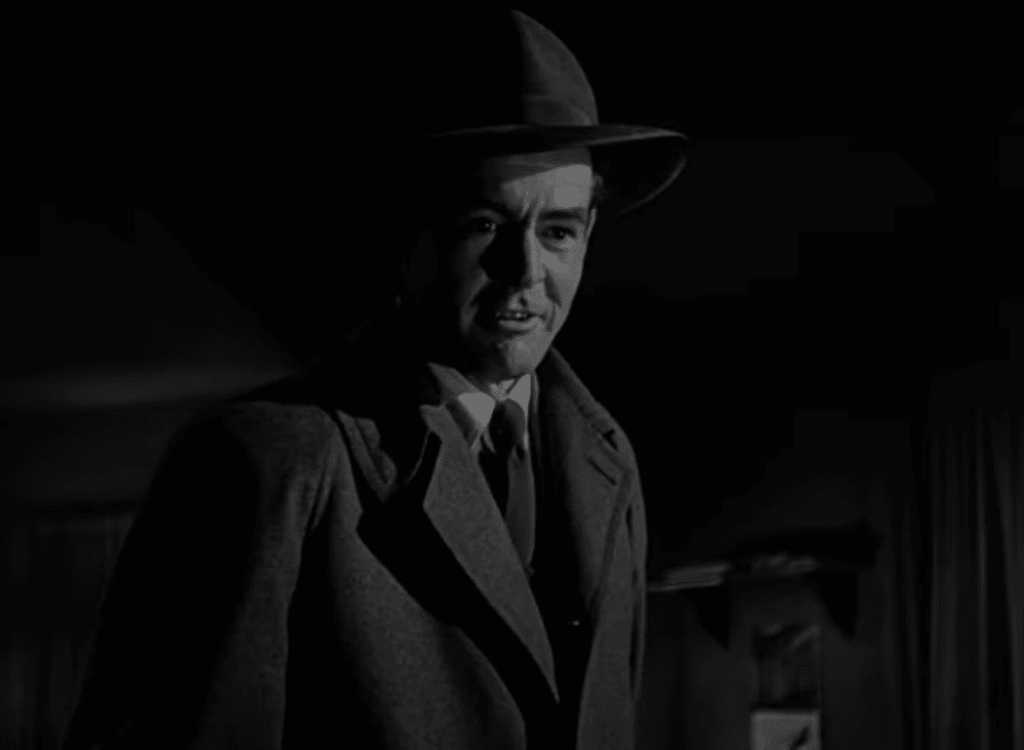

Wilson is another species entirely. He eats alone at a table memorizing the faces of men in mug shots. A violent, angry man himself—Robert Ryan often brings a gratifyingly villainous edge to his heroic roles—it’s as if Wilson is hallucinating his future beatings and apprehensions of men he suspects are the cop-killing scum of the earth, all while scraping his dirty plate into the trash in a lonely little room.

That the city in On Dangerous Ground is never identified by name is one of its dreamlike qualities, but the problem is the dreamer. Wherever Wilson looks on the streets, he sees a reason for rage or disgust, whether it’s an underage temptress in a bar, the offer of a smirking bribe, or the cop killers he beats witnesses to find. When he seethes in anguish, almost in tears—“Why do you make me do it? You know you’re gonna talk. I’m gonna make you talk”—to a suspect he’s about to beat half to death, it becomes clear that here we have a man whose violent nature expresses an operatic over-sensitivity. Lucky for us he also has Robert Ryan’s molten-steel face, with all its angular pain and glitter.

When he breaks down after beating another suspect, Wilson asks Pop Daley, “How do you do it? How do you live with yourself?” Daley rebukes him. “I don’t,” he says, “I live with other people. This is just a job like any other job. I do it the best I can. It’s never enough, but I do it.” Wilson can’t realize it’s only a job; he’s not a civil servant. He’s on some quest of excruciating, self-righteous despair and desire.

Defining the moral universe of the film, Daley suggests that the way Wilson is going he “won’t be good to anybody, not even yourself…to get anything out of this life, you gotta put something in it.” Daley all but tells him that a man on his own might reasonably devolve into bitter violence. He has to become a husband and father: a real vote of confidence for mid-century masculinity. Wilson’s fury does indeed suggest misdirected passion. Only crime seems to excite him, in the negative sense, and while it necessarily has a homoerotic overtone—that fixation on suspects and low lives—the film focuses most clearly on his pure loneliness.

Wilson soon affirms the idea when he tells his captain, with a touch of earnest reality, that “cops have no friends; nobody likes a cop, on either side of the law.” This is not, however, a political statement. It’s self-defense, almost sneering. If only Wilson could unsee what he’s seen—appropriately enough for a film in which he will feel the power of redemptive love with a blind woman who sees the world so much more fully than he does. Not to offend, but this dreamer needs a bit of blindness in his life. Seeing things the way he sees them, with his particular passion, he’s merely a “gangster with a badge,” to borrow his captain’s phrase.

The camera works into some cramped spaces while On Dangerous Ground lingers in the city. Uncommon for the era, there is a flourish of handheld shots in an alley chase scene, where Wilson runs a suspect down. The camera also peeks from the back seat of the cops’ car as it surveils the street, tracking people on the sidewalk. We see in these scenes as if from Wilson’s anxious, roving eye. The music by Bernard Herrmann, famous for his Hitchcock scores, doesn’t hurt either.

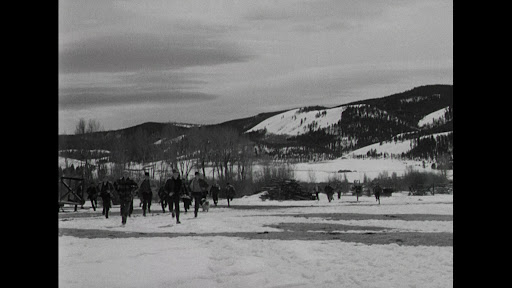

As it’s necessary for the main plot to get Wilson out of the nightmare, his captain packs him off for the country after he beats a suspect in the alley. He can cool off, literally, while helping apprehend the murderer of a young girl in a place that is clearly the mountains of Colorado but, like the city, never named. Here the camerawork and film itself leave behind urban noir and take an excursion into the western. Wilson even meets his hick counterpart in Walter Brent (Ward Bond, playing it broad but with feeling), the murdered girl’s trigger-happy father. Brent hardly cares about jurisdiction or the professional procedures of crime and punishment. “It’s gonna be my gun that takes care of him when we get him,” he says, “I’ll get him… and when I do there won’t be any of your city stuff: no fancy trials, no sob sisters, just gonna empty this shotgun in his belly.” Wilson immediately seems a bit more cosmopolitan by contrast. He senses the difference himself, feeling a bit less the fanatic and a little more like the professional we know he isn’t. He’s primed for a journey of the soul.

Enter the blind Mary Malden (Ida Lupino), and with her the final gambit of the film’s metaphorical intent. Malden lives in a remote house with her brother, Danny, who is both mentally ill and, inevitably, the murderer Brent and Wilson are seeking. No one clearly explains the details, but the audience understands that while Danny should be punished, he can nevertheless be sympathetically forgiven for what he’s done. Malden tries to hide the fact of her brother, but it’s plain to Brent and Wilson.

While Brent gives chase, Wilson sits with Malden in her lonely cottage and begins to realize he has a soul after all. Maybe he could even be a husband. Lupino’s poise and smoky voice make Malden seem every bit a person who has learned not to turn her solitude to bitter recrimination. Sensing Wilson’s distance, she tells him that “most lonely people try to figure it out, about loneliness.” She has love and grief rather than contempt for the world. Moreover, she tells him, as a blind woman she has to “trust everybody,” in contradistinction to his easy cop’s distrust, based as it is on a cultivated rage. Wilson’s prior claim of the necessary loneliness of the cop looks falsely reassuring now. Even his violence comes across sulky compared to Malden’s fatalism and sympathy for her frightened, murderous brother, her sympathy for the whole lonely species.

Wilson is in love already. He decides Danny should be brought in humanely. Nevertheless, he and Brent have to climb a mountain to get the kid. It’s like some sort of ritual, complete with a sacrifice, after which everyone starts to behave a lot more seriously, with respect and solemnity, even awe at the painful reality of fate. “Just a kid,” Brent says in shocked wonder. He sees more clearly, but the world is even more messed up than he thought.

Mary Malden already has the world-weary attitude the film finds proper for her tragic sense of things. Despite her clarity about her troubled brother—she believes he should have been institutionalized or somehow removed from endangering others—her final speech in the film declares plainly that people can live for others. Her brother was her “eyes”, bringing the world to her from the outside. And here she takes a turn that is the most moving in the film, for she outright rejects Wilson’s offered help. She refuses, most pointedly, Wilson’s somewhat sudden and perhaps compensatory love: “The way you are,” she says, “I don’t see how you can help anybody.” She turns, I think, to desolation, in her version of Wilson’s depression. Finally alive with what Pop Daley prescribed for him, Wilson can only look on, sad and hurt, at Malden’s disregard for her own pain. He realizes, too, his unwelcome condescension.

So what do you make of a problematic ending? Wilson drives home wearing Robert Ryan’s agonized face. He remembers what Malden told him and what Pop Daley pronounced about him. A man like him should interrogate his loneliness, his hatred, his desperate sensitivity to a world that is both as harsh as he imagines and as full of love as he could dream. Maybe the whole film now seems like the despairing nightmare of a lonely man driving home to the ruin of his life. Or, at least, that’s the power of Robert Ryan’s face. The brief and problematic ending looks like second thoughts on the part of the filmmakers, who seem to have tacked on an affirming and abrupt consummation of romance between Wilson and Malden. You have to see it to really grasp its sentimental reversals, and its wish fulfillment, although I do find it moving in a way.

For what is good in On Dangerous Ground to matter most, you have to read the final scene as a dream sequence, not unlike the voices Wilson remembers as he is driving away in his car. Ida Lupino’s final “thank you” feels like the real ending of the film; I’d like to write at length about the peculiar ambiguity of that “thank you,” which is also a farewell and may not be as sincere as it seems. But the point is that On Dangerous Ground should be—and fundamentally is—the sort of film that inspires the democratic uncertainty of post-film viewing. People should argue about the ending; people should form sides and debate the finer points of romantic fatalism and the reality of loneliness and how it feels to think the world is shit and whether that feeling is itself a form of illusory consolation. hey should talk about Robert Ryan’s face and whether it really redeems with its ambiguous spiritual suffering and desire, the hatred and violence with which it tries to offload his despair. The very end of On Dangerous Ground must be a dream sequence, or else—taken literally—it mars the fresh ambiguity of the film’s final scenes, the dream of loneliness, the possibility of love, the nightmare and freedom of being a person.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon