| Dan Howard |

Good Morning plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, December 6th, through Sunday, December 8th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

In this day in age, television is just as common and almost essential to our daily lives as food or nature. Sometimes, it feels like it’s just always been around, but in fact, the first concept of what would ultimately become television, Facsimile Transmissions, was introduced around 1843 and the first televised broadcast occurred in 1927. RCA subsequently introduced the first fully functional television set in 1936. Yet, around 1959, with television in many homes it still felt like a revolutionary and brand new technology—embraced by the young and not fully understood by the older generations. It’s amazing when you take a step back and consider exactly how long a piece of technology has really been around, yet still seems new to most of society. Each new technological advancement can test a generation that are set in their own traditional ways and affect their ultimate worldview. Who better to explore this mindset than a master of cinema like Yasujirō Ozu?

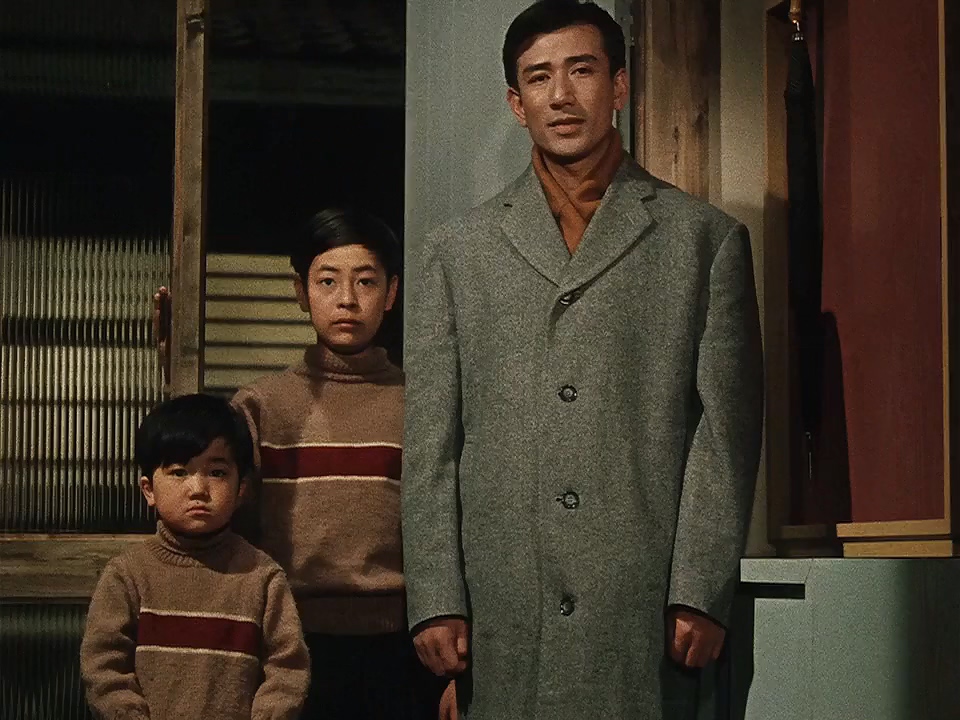

In the Japanese maestro’s comedic and heartfelt film, Good Morning, we follow the daily lives of two brothers, Minoru (Shitara Koji) and Isamu Hayashi (Masahiko Shimazu), as they navigate school and home life while pleading with their parents to buy a television set for their home. When their mother insists on not buying a TV after they disobeyed her by sneaking over next door to watch TV, the boys take a vow of silence and begin a hunger strike until their parents buy them the television set. In turn, their parents and others of their generation attempt to understand and embrace the imminent change in the world they have known for so long. Throw in some good fart humor and you have a masterpiece!

There is plenty of subtext that lies dormant within the layers Ozu’s work, and while it doesn’t directly mention “tradition” as a topic of concern, its principles permeate Good Morning on multiple levels. With every passing generation, we see how the younger generation affects the elder generation through the ever-changing landscape of technology. Younger generations also tend challenge traditional ways of thinking and living. In Ozu’s film, the parents seem to make at least some effort to embrace the modern world, having their children take English lessons and developing a desire to have something as new as a washing machine in their homes. However, the adults in the town often seem to contradict themselves when faced with the task of simultaneously upholding their ideals and deciding which aspects of the modern world shall become part of their lives. They teeter between wanting to live a simple life and envying their neighbors for having these nice up-to-date things.

Alluring inventions aside, they are mainly concerned with “paying their dues.” The women do so for their own local Women’s Club and the men work to provide for their families. Pretty normal sounding for small town life. We witness the effects that small town life can have on the psyche of the adult characters when the chairwoman of the Women’s Club, Kikue Haraguchi (Haruko Sugimara), claims that Tamiko (Kuniko Miyake), Minoru and Isamu’s mother and treasurer of the Women’s Club, never turned in their collective dues. Tamiko respectfully denies this, and claims she clearly remembers turning in the dues. This ultimately sinks Kikue into suspicion. Who does Tamiko think Kikue is? Everyone will think that Kikue is a liar who stole the money to buy the washing machine that Tamiko is so envious of, right? This line of thinking leads to Kikue spreading a rumor that Tamiko holds grudges. That is, until a realization comes that Tamiko gave the dues to Kikuo’s mother, but her mother had forgotten all about it. Ozu brilliantly displays the characters’ narrow view of their world via the various shots of passersby on the road above the neighborhood, as well as other people walking in the space between the roofs of the houses. Their town is their whole world, and the outside world can seem of minimal importance when enclosed in one’s own world. This, however, makes the way the children of the story view the world that much more refreshing and hopeful.

Their parents do have good intentions. However, the fact is the boys don’t seem to share in their parents’ ideals and often skip English lessons to watch sumo wrestling. Why not let them watch TV? At their age, it’s the only way to see the world outside of their small rural town. Minoru even accuses all the adults of talking a lot but not saying anything. This friction between the kids and their parents is the core message Ozu is trying to convey. Something we see even today is the different generations finding faults in each other, attempting to prove how their generation and their way of life is superior and that these “kids” and/or “geezers” don’t really know anything. It feels like each generation wants to uphold their traditional ideals as much as possible. Ultimately, I think Ozu’s film can be best described as a cautionary tale centered around missed connections and misunderstandings in terms of families being ignorant of their child’s/parents’ point of view or even how we treat our neighbors.

When we’re young, the older generations seem just out of touch and “lame” and the older we get, the less we seem to understand the younger generations and feel out of touch ourselves. Mr. Tomizawa (Eijirô Tôno), a bar patron and friend of Minoru and Isamu’s father, Keitarô (Chishû Ryû), struggles with feeling out of touch throughout the film, expressing frustration to Keitarô about retirement. Tomizawa, I believe, serves as a perfect connection between the two generations of the film’s central family. Later on, we see him partaking in the same activities such as playing the kids’ fart game. A funny and heartfelt moment that Ozu incorporates as the best way for the generations to bond: holding on to one’s youthful nature. After all, word gets around fast in a small town and could get back to Minoru and Isamu’s parents about Tomizawa’s newfound youthful nature. Perhaps it could trigger a change of heart in their views about what TV means to their boys?

Often, spending time around joyful youth can help one feel young again. Whether we differ from our parents or are like them, we probably will reach an age where we start to appreciate the simpler things in life. We even see it in the blossoming love between Heiichriô (Keiji Sada), the boys’ English tutor, and Setsuko (Yoshiko Kuga), whose father Heiichirô works for, writing out translations for him. Different generations very rarely completely understand each other, but the main message here is to continue viewing the world with a never-ending curiosity. Perhaps it was Ozu’s way of reminding all of us to keep our inner child alive and well.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon