| Matthew Christensen |

Shanghai Express plays at the Trylon Cinema Sunday, November 3rd, through Tuesday, November 5th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

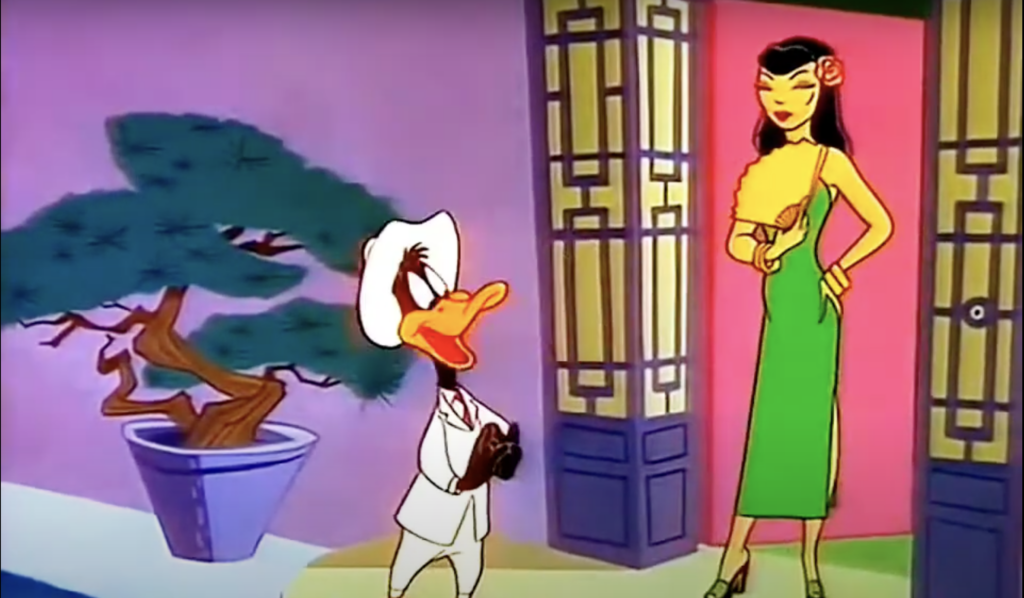

As a kid, we used to play a game called “Statue Maker.” The statue maker would swing two or three kids about; they had to hold the pose they landed in and come up with some character to portray. Other children would play customers, guided about by the statue maker who pushed a button allowing her creations to come to life. In general, chaos would ensue with all manner of animated lions, Casanovas, and gladiators terrorizing the gleeful “visitors” who had to choose a statue to take with them. It was the kind of game that fueled my imagination and I was eager to create characters. I remember being inspired by a Looney Tunes rerun I had seen one Saturday morning called “China Jones” (Warner Bros., 1959). It featured Daffy Duck and Porky Pig. The story follows Daffy, who plays the eponymous detective, working on a case in Hong Kong after receiving a plea for help in the form of a fortune cookie. I don’t remember too much about the rest of the story except for one moment. China Jones follows a lead which takes him to the home of a woman called the Dragon Lady, who literally breathes fire on the unsuspecting duck, leaving him charred, featherless.

In the game, I let the statue maker fling me in a way that resulted in my standing in what I imagined was an exotic, provocative pose, one that would not give away the fact that I was a dangerous, fire-breathing dragon. I conjured, in my unfettered little boy mind, an image of myself as the Dragon Lady with long, black hair, wearing a green silk cheongsam. I realized my choice was a disaster the moment the statue maker pushed the button to animate me. In my excitement over the game, I completely forgot that there was no way for the other kids to see flames coming out of my mouth much less for me to convey the idea of flames in any compelling way. I was just a stupid nine-year-old with his mouth gaping open.

What this rather pathetic anecdote is leading up to is the fact that that was the first time I had heard the term “dragon lady.” Although I had no context to connect it to a racist stereotype of Asian women, looking back, I am amazed at its pervasive acceptance well into the 1970s when I first saw the rerun. Yes, the cartoon was a product of the 50s, but it could hardly be relegated to a bygone, post-war mindset given the fact that it was very likely that I could have seen in the same sitting a popular commercial for Calgon water softener which also played into stereotypes with its Chinese couple running a laundry and joking with a white customer about “ancient Chinese” secrets. The truth is that as a child watching the cartoon, I would have been fascinated by what I would have perceived as exotic, but I would have given little to no thought about the harmful stereotypes also portrayed. It was just a funny cartoon.

When I consider Joseph von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express (1932), a film I hadn’t seen until a little over a year ago, I must admit that there was still an element of the exotic for me exemplified in the title. The name harkened back to the golden age of travel, to the allure of the unfamiliar, to tales of international intrigue. And it is perhaps that loaded word “exotic” that often allows us to separate ourselves from the more problematic elements in a film.

Shanghai Express follows an odd assortment of travelers—a missionary, a prudish matron of a boarding house, an American gambler, a German opium dealer, a British captain, a French officer, a rebel warlord incognito as a passenger known as Henry Chang, and Shanghai Lily and Hui Fei (two women described as “living by their wits,” a euphemism for prostitution)—on a train from Peiping (Beijing) to Shanghai during the middle of a civil war. Over the course of the journey, Henry Chang, with the aid of his rebel army, commandeers the train and holds the passengers hostage while negotiating the return of one of his henchmen captured by the Chinese government. At the heart of this intrigue is the fractured relationship between former lovers Captain Donald, “Doc,” Harvey and Shanghai Lily (Marlene Dietrich), once known as Madeline. During interrogations, Chang invites Lily to come to his palace as his lover, setting off two critical events. First, Doc Harvey jealously confronts and physically attacks Chang, placing him in a precarious position despite being a valuable hostage and bargaining chip. In revenge for the attack, Chang plans on blinding Harvey with a hot poker before returning him in the hostage exchange. Second, Chang’s frustration at not being able to possess Lily, leads directly to his rape of Hui Fei (Anna May Wong).

Sternberg invites us to see Lily and Hui Fei as connected almost immediately as their arrivals at the station are parallelled in an East/West manner: Hui Fei arrives first in a Chinese sedan chair, then Lily in a private car. The two are further paired through their shared profession as prostitutes. The missionary, Reverend Carmichael, first labels Hui Fei when he boards the train, demanding the porter change his compartment: “I haven’t lived for ten years in this country not to know a woman like that when I see one!” Hui Fei sits in the background, eyes staring through the minister. When the porter removes Charmichael’s luggage, the camera dramatically cuts to the first of many close ups in the film of Hui Fei. Her eyes follow Carmichael out of the compartment as she calmly holds her cigarette. Wong’s eyes shift from a venomous gaze to something more ambiguous, even vulnerable. While it might be tempting to cry out, “Male gaze!” there is less objectification happening in this moment. Rather, Sternberg is setting up an image of isolation here, which creates a sense of difference amid the multiple comparatives with Lily. In the very next scene, an officer informs Captain Harvey that he is in for an exciting journey as Shanghai Lily is aboard the train. Harvey fails to connect the name to his former lover Madeline. As the officer goes on to describe her as a “coaster,” the conversation drifts down the corridor where Lily has entered Hui Fei’s compartment. Lily stares out of the compartment door as she closes it. Framed in another compartment window, Hui Fei stares at Lily with a look acknowledging their shared status. Wong is constantly depicted in this way, framed within frames, a compositional device that both highlights her and isolates her.

Moreover, the narrative roles of these women parallel in bringing about resolution to the film’s central conflicts. Lily is prepared to sacrifice herself and stay with Chang as his lover to prevent the warlord from blinding Harvey. Hui Fei obviates this necessity by killing Chang in a personal act of revenge for his assault. Lily’s sacrifice brings about romantic resolution, leading to renunciation of her profession and a happy recoupling with Harvey. Hui Fei’s retributive act in turn satisfies the audience’s need to see justice served. But it goes further than this. By avoiding the cliché of a final showdown between the two men, Chang and Harvey, Sternberg is able to keep his female protagonists, Lily and Hui Fei, at the center of the narrative. While the choice does partly reinforce the stereotype of the dragon lady for Wong, Sternberg gives Hui Fei agency, allowing her to not only avoid paying for the crime of committing murder, but also to collect the reward offered for Chang’s apprehension, dead or alive.

While the film was almost certainly a vehicle to further elevate Dietrich’s justifiable box office popularity, it is Anna May Wong who stands out. As Hui Fei, Wong portrays a woman whose every line, gesture, and glance conveys a loathing for the people and systems that have relegated her to a life of prostitution. Yet Wong’s characterization is also somehow able to articulate a kind of proud resignation, the kind that dares anyone to judge her. This defiance against social convention is most clearly seen early on in the film when she, like Lily, rejects Mrs. Haggerty’s offer of a place at her boarding house for respectable women, stating wryly, “I must confess, I don’t quite know the standard of respectability that you demand in your boarding house.” In looking back at this film with 21st century eyes, one cannot help but wonder if Wong’s performance channeled the understandable frustration the actress must have felt as a Chinese American working in Hollywood in the 1930s. In a film set in China, but filmed in a Hollywood studio, with a cast whose only other major Chinese character, Henry Chang, was Swedish-American actor, Warner Oland, in yellow face, Wong’s performance reads as a wearily angry indictment of the limitations of a studio system designed for white stars. While certainly Sternberg, with the help of cinematographer Lee Garmes, visually challenges audiences to see Shanghai Lily and Hui Fei in the same light, he also separates them through frames within frames. This compartmentalization invites us to consider the cultural contexts and biases that separate these women despite their similarities.

That Anna May Wong’s riveting 1930s performance is able to transcend the dragon lady stereotype suggested to me in my 1970s childhood by a Looney Tunes rerun from the 1950s is more than a little gratifying reminding me of the last lines of a Margaret Atwood poem:

You think I’m not a goddess?

Try me.

This is a torch song.

Touch me and you’ll burn.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

Your review captures the allure and deeper message of Shanghai Express perfectly. Your childhood memories of stereotypes in cartoons also add a thoughtful layer, showing how these images stay with us over time and shape how we view films like this.