| Nicole Rojas-Oltmanns |

Beijing Watermelon plays at the Trylon Cinema Friday, November 1st, through Sunday, November 3rd. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Unlike coconuts, mangoes, apples, cherimoyas, plantains, and pineapples, everyone knows what to do with a watermelon. Cut and enjoy. They grow in the vast majority of the world from Sweden to Japan, USA to Chile, China to Israel. Perhaps, because of this, watermelons have the power to break barriers and connect us all. Stay with me on this.

In Beijing Watermelon (1989, directed by Nobuhiko Ôbayashi), a Japanese produce seller, Shunzo, out of guilt, empathy, or a combination of the two, helps support Chinese exchange students. This begins when one student is unable to afford vegetables and suggests they play rock-paper-scissors to negotiate a cheaper price. The student wins the vegetables, but needs more support as time goes on. Shunzo continues helping students as they come, and go, and grow in number. On a special outing to the beach, his relationship to the students is cemented.

Enter the watermelon. The students play a game to smash open watermelons provided by Shunzo for the occasion. This scene is made more powerful given the history between China and Japan in WWII and the political conflict in Beijing at the time of filming. They sign songs together about the ocean in both languages. As one homesick student begins to cry while eating the watermelon, national pride flairs momentarily as the taste of Japanese and Chinese watermelons are compared. However, continually throughout the film, their Chinese Japanese Friendship is revered.

After all of the students have graduated, they follow a Chinese proverb, “A drop of water shall be returned with a burst of spring,” and gift money and a Chinese-grown watermelon to Shunzo.

A good time to mention that watermelon is a natural diuretic. The more you eat, the more you pee. At a memorable potluck several years ago, the youngest child in our care, then 2 years old, ate an impressive amount of watermelon in one sitting. Having been recently potty trained, the diuretic effect of watermelon overpowered the new skills and when it began to rain shortly into the event, we could no longer tell which water was which. “A burst of spring” indeed.

In case you haven’t seen it, and you should see it, Dirty Dancing (1987, directed by Emile Ardolino) is not about dancing. Well, it’s not entirely about dancing. When Baby and her wealthy family stay at a dull resort in Upstate New York, she goes looking for something more. When she runs into one of the workers, she helps him carry watermelons into the staff party. In possibly the best meet-cute of all time, she explains why she is there to Johnny, the lead, by saying, “I carried a watermelon.” Yeah she did.

Eventually, Baby and Johnny break through class, education, and dance barriers to be together. All because of a watermelon.

Once a week, my brother-in-law would come over for dinner and a movie. He admitted that he had never seen Dirty Dancing, so we decided to watch it, of course. Morning of, he texted to ask what he could bring to go with dinner. When he arrived, I asked him, “Whatcha got there?” and he said, “I brought a watermelon.” Yeah he did.

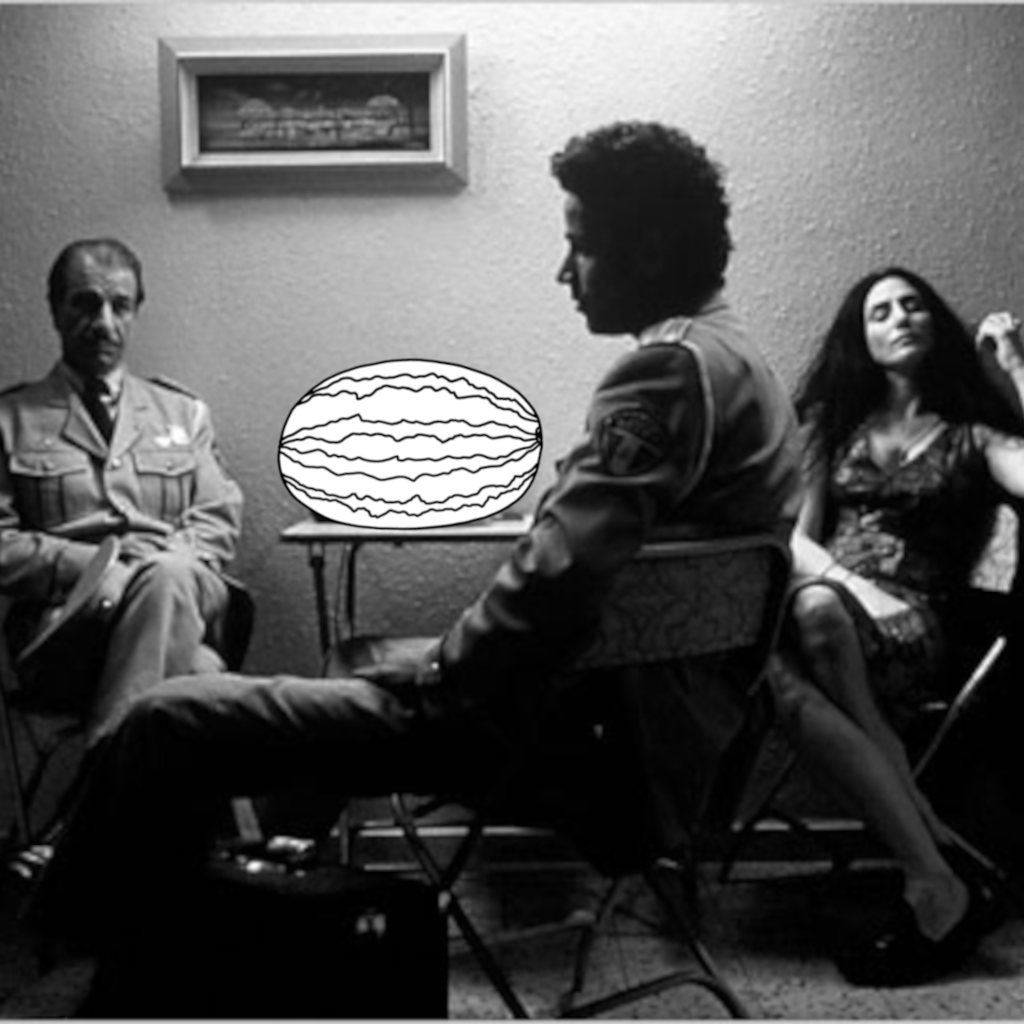

The Band’s Visit (2007, directed by Eran Kolirin) is a brilliantly subdued, yet hilarious film where an Egyptian military band accidentally ends up in a tiny Israeli desert town where they involve themselves deeply in the lives of the locals over the course of an evening.

The main host, Dina, is a disheveled yet functional Israeli restaurant owner and dreamer. When asked where the Arab Cultural Center is, she responds, “No culture. Not Israeli culture, not Arab…no culture at all.” Dina forcefully cuts open a watermelon into uneven chunks as a way to break the ice between herself and the Lieutenant-Colonel Tawfiq.

The watermelon is the first of many actions that connect the characters across the lines that seek to separate: rural/urban, Arab/Israeli, military/civilian, and formal/casual.

We have a house a block away from 38th and Chicago. Amid the frequent chaos and conflict, there have been many beautiful moments there. One was watching a watermelon vine stretch across a small patch of green on a corner of the intersection. Several watermelons grew large and ripe in the direct sunlight there. I watched the first one get harvested. You can do nothing but smile while holding a freshly harvested watermelon. Try it.

La Sandia/Vattenmelonen (2006, directed by Gorki Glaser-Müller) is a short film about finding pieces of home wherever you end up. Both words mean “watermelon.” The first in Swedish. The second in Spanish. Many Chileans fled Chile after the military coup in 1973. They ended up all over the world. The director was born in Chile a month after the coup. He left for Sweden when he was 13.

The father in the film arrives home with a small spherical watermelon. He was supposed to buy bread and milk. There wasn’t enough money for needs and wants. The kids can’t even remember what watermelon tastes like. They wait to eat it until after dinner. The father reads Pablo Neruda’s poem, Ode to a Watermelon. (I have read this poem to the youngest child who loves watermelon.) When they can wait no longer, the mother cuts it in half to find yellow instead of red. They think it’s bad. Magical realism ensues, perfectly done, until they realize watermelons are often yellow in Sweden.

Half of my wife’s family is Chilean. Fruit there is like wheat here. The youngest child and I went to a farmers’ market blocks away from Neruda’s Isla Negra home. We bought a kilo of cherries for the equivalent of 2 dollars. We bought a watermelon.

You may end up far from home, but most likely, they’ll have watermelons there too.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon