|Andrea Buiser|

Manila in the Claws of Light plays at the Trylon Cinema one night only on October 17th, resented by Archives on Screen. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

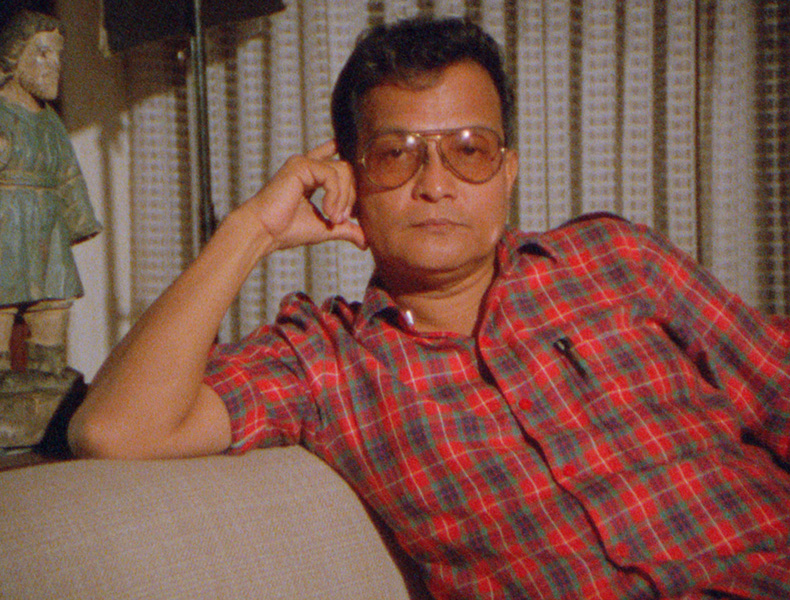

Lino Brocka was born in the province of Sorsogon in 1939, in what was then an unincorporated territory and commonwealth of the United States that existed from 1935 to 1946. Growing up in a setting that shaped his understanding of social inequality, Brocka’s early life was marked by personal tragedies, including the death of his father, which prompted him to pursue a religious vocation. However, Brocka ultimately found his calling in the arts, particularly in film. In 1983, Brocka co-founded Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP), a collective opposing state censorship under the Marcos regime, more specifically, to Imelda Marcos’s stance on presenting Filipino arts to her own liking rather than giving artistic freedom.

Manila in the Claws of Light reflects this deep commitment to the underrepresented and the disenfranchised, criticizing the social structures that perpetuate inequality. Brocka delivers an urgent response to the political and economic turmoil in 1970s Philippines. His films consistently tackled social issues, including poverty, corruption, and human rights violations—issues that were especially relevant in the Philippines and have lasting influence on filmmakers today. One of the most evident influences of Brocka’s style on other contemporary films about class struggle is their use of social realism to portray the harsh realities of urban life. The city is an oppressive force, trapping individuals in poverty and exploitation, much like how contemporary directors like Bong Joon-ho and Sean Baker employ urban landscapes to intensify their social critiques.

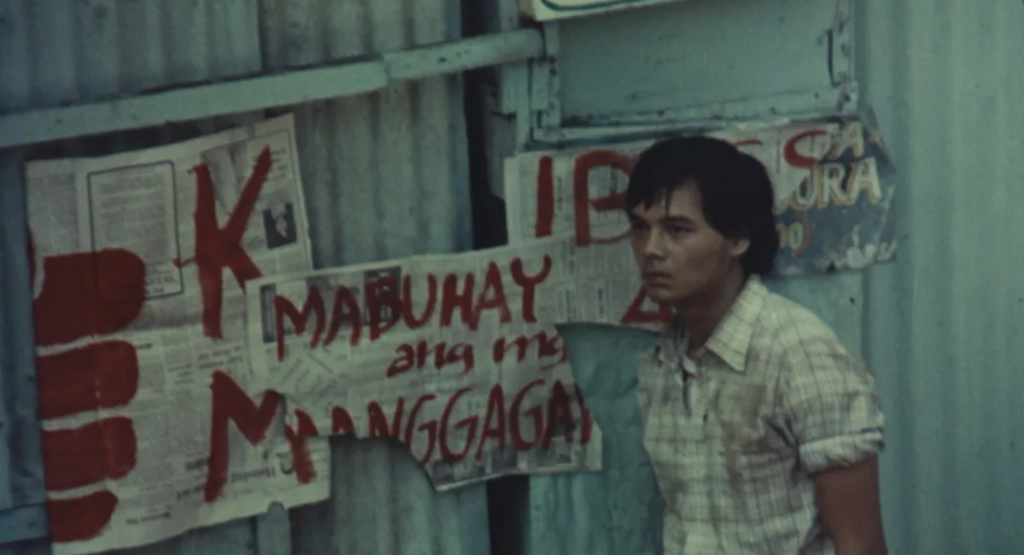

A central theme in Manila is the inescapable nature of poverty, and how the system perpetuates suffering for the lower class. Protagonist Julio’s journey through Manila is a constant reminder of the barriers that prevent upward mobility. He is exploited as a construction worker, preyed upon by corrupt middlemen, and denied any real hope of escaping his circumstances.

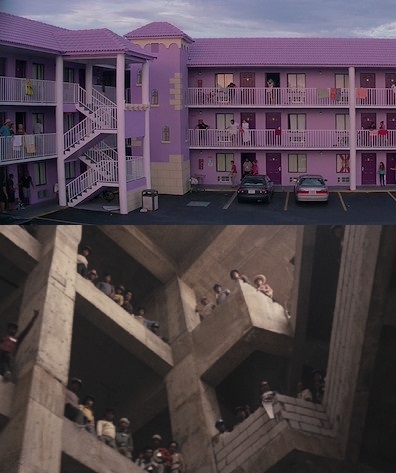

Similarly to Manila in the Claws of Light, Sean Baker’s The Florida Project is set in a rundown Orlando motel on the outskirts of Disney World, a location that starkly contrasts the fantasy of wealth and happiness associated with the theme park. Both films use urban environments to highlight the socio-economic structures that keep the marginalized in place.

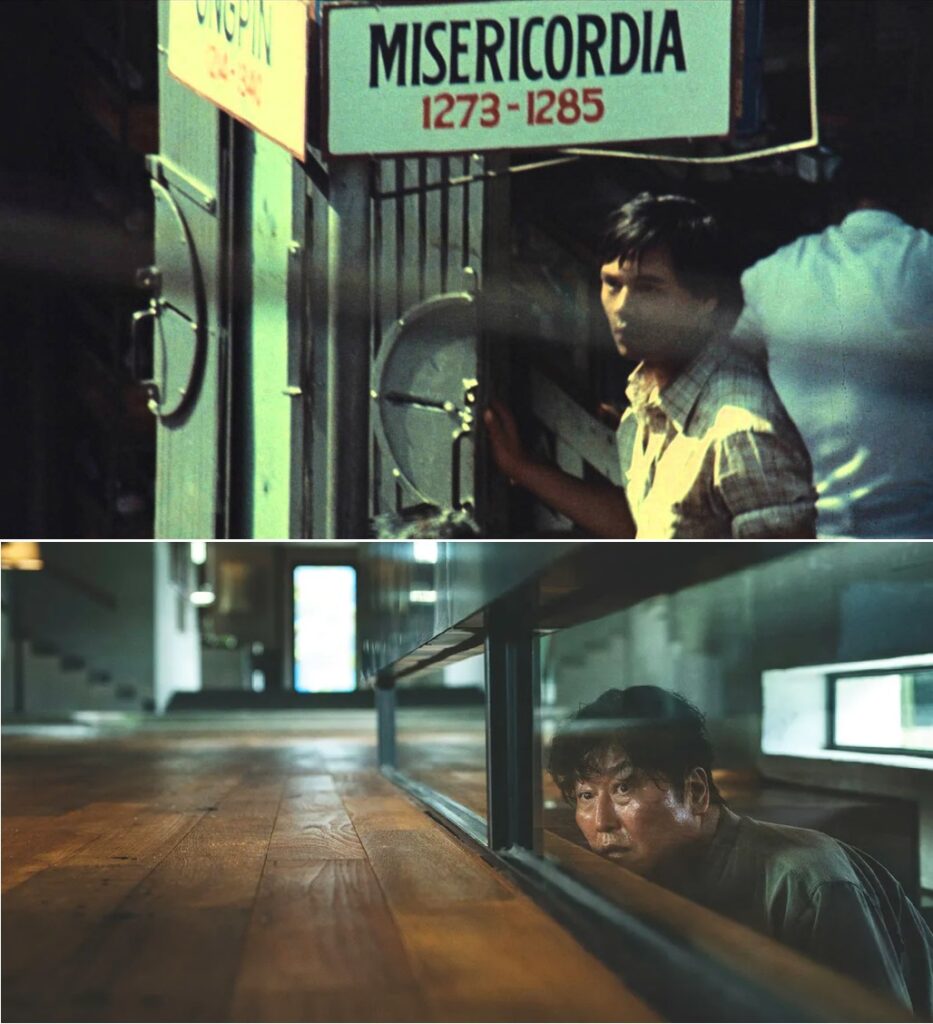

This sense of entrapment by the economic system is also echoed in Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, where the Kim family’s attempts to climb the social ladder ultimately lead to disastrous consequences. Despite their cleverness and resourcefulness, the Kim family remain victims of a deeply entrenched class hierarchy that is as oppressive as it is invisible. Reminders of class struggle in Manila are everywhere, such as signs painted on newspaper saying, “Mabuhay ang mg manggagawang”, or “Long live the workers.”

Parasite critiques the illusion of social mobility in modern capitalist societies, much like Brocka critiques the false promises of a better life in the city. Both Parasite and Manila in the Claws of Light explore how the poor are often trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty, where any attempt at escape leads to even greater suffering. Brocka’s ability to create visual and narrative tension through his depiction of inequality is another element that resonates in the works of Bong Joon-ho and Sean Baker.

In Manila, Brocka contrasts the hustle and bustle of Manila’s streets with moments of quiet despair, creating a sense of suffocating tension. Bong Joon-ho uses similar techniques in Parasite, with the cramped, semi-basement apartment of the Kim family juxtaposed against the vast, luxurious spaces of the Park family’s home. This visual contrast underscores the stark inequalities that drive the film’s narrative.

Sean Baker’s The Florida Project presents a more subdued yet equally potent exploration of poverty, focusing on the daily lives of children living on the fringes of society. Like Brocka, Baker is deeply interested in the ways systemic poverty shapes not only the present but also the future. Moonee, the young protagonist of The Florida Project, lives in the shadow of Disney World—a symbol of wealth and fantasy—yet her reality is marked by instability and economic precarity.

Manila in the Claws of Light is arguably Brocka’s most famous work. At its core, Manila is an indictment of the dehumanizing effects of poverty and the systemic injustice that pervades the city. The city of Manila, in Brocka’s hands, is a predator that traps those who are already marginalized and keeps them in suffocating conditions.

Through their shared focus on social realism, humanizing the marginalized, and critiquing systems of power, Lino Brocka’s legacy lives on in contemporary global cinema. His work continues to inspire filmmakers to tackle difficult social issues with honesty, compassion, and artistic integrity, ensuring that his influence endures long after his time.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon