|Chris Polley|

A Tale of Two Sisters plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, October 20th, through Tuesday, October 22nd. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

For many who have endured a ninth grade and/or AP literature class, Shakespeare brings to mind big emotions and melodramatic ideas: forbidden romance, corrupt monarchs, or mistaken identity. An underrated aspect of a good chunk of his work, however, is its exploration of the horrors of the great beyond (which is, so often, found within). The three witches of Macbeth, the several spirits of The Tempest, and—arguably most notably—the solitary ghost of Hamlet.“ The Bard’s impact on supernaturalism and the Gothic genre is equally as significant as his other writings on power, English history, death and love,”1 writes Colin Yeo for The Conversation. Likewise, we still see this frightful element in a very specific brand of modern horror movies—in fact, this type of creature feature isn’t even from an English-language country, but rather from another prominent cinematic continent: Asia.

Of course, Shakespeare’s tragedies famously inspired one of the Japanese masters quite directly, as the great Akira Kurosawa reimagined many a canonical Elizabethan text, including 1957’s Throne of Blood (a reworking of Macbeth, minus the witchcraft) and 1985’s Ran (an epic adaptation of the equally epic King Lear). None of these, however, really emphasized the supernatural elements present in their source material. It wasn’t until the popularization of the horror movie in Asia, beginning with 1960’s landmark South Korean thriller The Housemaid and 1964’s Japanese curse fable Onibaba, but not really taking hold as a trend until 1998’s Whispering Corridors and 1999’s Memento Mori. Director Kim Jee-woon took advantage of the boom in elegant fashion for 2003’s A Tale of Two Sisters: combining gothic horror, Shakespearean tragedy, and a famous folktale from his ancestors, this trifecta proved a winning combination, as the film not only became a smash hit in South Korea, but it also cemented its place in history as the first Korean film to be properly released in American theaters.

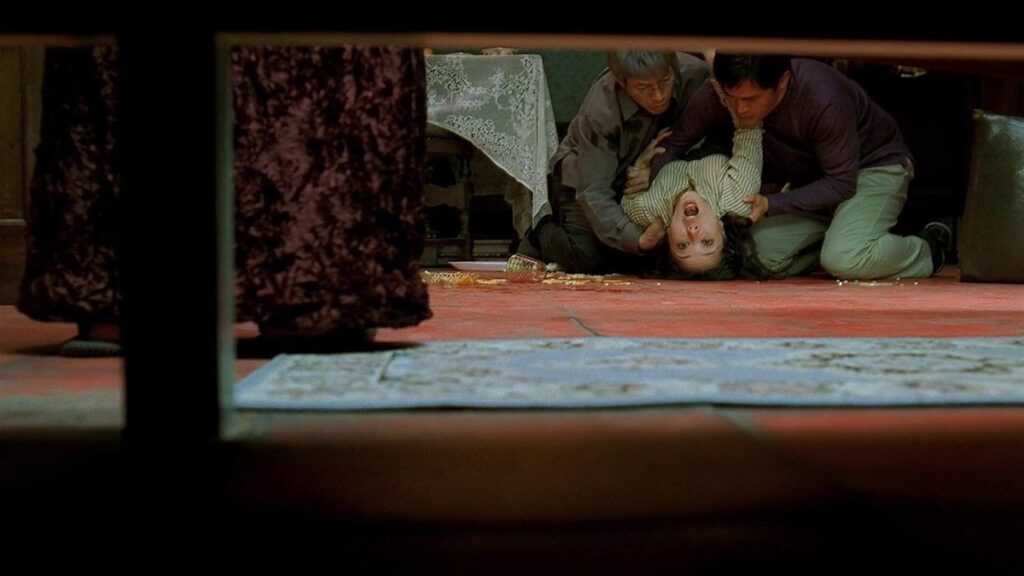

Known genre-hopper Kim tackled the burgeoning genre horror with a tried and true story of old repackaged with a stately, ornate flair that was both immediately bold and familiar to audiences. Based on the folktale “Janghwa Hongryeon jeon,” the popular story had already been adapted for the silver screen five times before Kim put his stamp on it. Kim spoke to Electric Sheep about his foray into horror, saying of his third feature, “When I chose horror, the theme of the film was the fear of things that you can and cannot see.”2 The focus was the madness of the mind and the horrors of a traumatized household—two themes that very much fall in line with one of literary history’s greatest tales: Hamlet. In Tale, Kim swaps a prince and the object of his affection for a pair of siblings (Su-mi and Su-yeon), and suspicions of a stepfather’s true nature for that of a stepmother (Eun-joo). In both, the central character is at odds both with a sordid family history as well as their own sanity.

The links between “Janghwa Hongryeon jeon” and Hamlet (an evil step-parent, familial ghosts, and a whole lot of violent deaths) are already there on the surface, but Kim takes the parallels and ratchets them up to 11 for his version of the story. One could say he even takes that aforementioned central struggle—that of the human apprehension of and inability to sometimes distinguish between the visible and invisible—to its logical endpoint. Korean folklore scholar Sung-ae Lee comments on the more recent retellings of the folktale, saying, “Numerous modern retellings—in all media—interrogate the possibility of any satisfactory outcome and hence dwell more on the tale’s capacity for chaos and mayhem and confront audiences with inexplicable uncanny components.”3 There is little room for resolution in Kim’s rendition of the tale, and that’s the fulcrum of its effectiveness as a work of horror. And while Shakespeare is able to retain some objectivity on stage through soliloquy and history, making Hamlet a complex but still ultimately sympathetic lead character, Kim opts for something wilder and less tangible.

While so many Western horror films focus on the external and the abnormal, whether it be killers or the devil incarnate, monsters or spirits with unfinished business, it’s not as simple in horror films like A Tale of Two Sisters, where the stem of the scare is internal and abstract—and not just for Su-mi, but for the entire cast of characters, and even the audience too. “For Asian horror films, we would reflect or think about the horror coming from inside ourselves,”4 Kim said to Fangoria earlier this year for a twenty-year retrospective on the film. Consider the many terrible-to-mediocre American remakes of Eastern horror films in the 2000s: Japan’s Ringu (1998) emphasized minimalist dread while Gore Verbinski’s The Ring (2002) heavily featured maximalist scares. Kim’s Tale got a similar treatment in 2009 with Hollywood’s The Uninvited, which unfortunately sucks much of the surrealism and introspection in favor of repetitive haunted house tropes. The kind of battle for one’s soul that is more frightening is the guilt from past deeds coming home to roost, made manifest not by an amoral villain or supernatural entity, but by one’s own subconscious.

Yet again, the links back to Shakespeare and more of the most time-tested classical literary works are made clear. Part of Hamlet’s eternal appeal lies in its radical refusal to share with the audience much of any discernible truth regarding the state of the mind of the titular Dane. Ultimately, the psychic break as depicted on stage and screen becomes a vital tool in both facing the horrors of introspection as well as understanding it. Dr. David McGinnis writes, “Shakespeare’s understanding of how the self related to its environment—to the natural and supernatural worlds around it—exerted a profound impact on the literary imagination of authors of gothic fictions in the late eighteenth century.”5 Kim is tapping into not only his nation’s past and the Bard’s but other Western hallmarks such as Shelley and Poe. Victor Frankenstein and the narrator who hears a heartbeat under the floorboards, just to name a couple, also have this uncanny ability to show the projection of the self, warts and all, while never truly answering to the reader whether this human darkness is something that’s ever able to be diminished, much less eradicated.

On a narrative level, Kim (like so many that came before him), suggests that at the very least, the interior black hole of memory and unatoned sins is never satiated. Like all the greats, Kim offers the only conclusion that is feasible: death of the self, whether figurative or literal—the eternal and only absolute loss guaranteed to all. “Su-mi is brought to destruction because she retains an innocence that makes her think she is the cause of all tragedies,”6 Kim said in an interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books. Just as when Hamlet is finally confronted with the massacre he put into motion in the name of uncovering a truth (as if it were something to be uncovered rather than ever-wrestled with), A Tale of Two Sisters suggests that the only truth that one can truly face is what one chooses to see, not something that can be left out of sight in the darkened corners of the mind.

- Colin Yeo, “‘Supp’d full with horrors’: 400 years of Shakespearean supernaturalism,” The Conversation. 20 April 2016. ↩︎

- Virginie Sélavy, “The Good, The Bad, The Weird,” Electric Sheep. 1 February 2009. ↩︎

- Sung-ae Lee, “Memory, Trauma, and History: Fairy-tale film in Korea,” in The Fairy Tale World, (June 2020), 360. ↩︎

- Nguyen Le, “Memorable Haunting: Kim Jee-woon on A Tale of Two Sisters,” Fangoria. 8 January 2024. ↩︎

- David McGinnis, “Shakespeare and the Gothic,” The University of Melbourne: Archives & Special Collections, Accessed 6 October 2024. ↩︎

- Michael Szalay, “iPhone TV: A Conversation with Kim Jee-woon,” Los Angeles Review of Books. 11 November 2022. ↩︎

Edited by Finn Odum