| Sophie Durbin |

Play it as it Lays plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 23rd, through Sunday, August 25th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

I know what nothing means, and keep on playing. (Final lines, Play It As It Lays, Joan Didion, 1970)

“If you’re worn out and under the weather, this movie can make you feel sophisticated. However, as it goes on and on, you suddenly feel like you have too much life in you to waste it on this film. Thank you for uploading it, sincerely.” (C.J. Berry263, reviewer of Play It As It Lays on archive.org, July 17, 2021)

The unexpected thread that I chased for Play It As It Lays was a comment a family friend made when she saw me doing my due diligence by reading Joan Didion’s novel of the same name. “Oh, that’s a good book,” she said. “I just had Lana Del Rey in my head the whole time when I read it.” I saw her point right away. Maria and Lana have a lot in common: beautiful and weary, talented and nihilistic, lagging behind the beat, taking their time, both open-minded about the inevitable tragedy of life—nothing really matters, so why not try to luxuriate in the nothingness? As I tinkered away with this blog post, listening to Lana’s album from last year on repeat, I concluded that to luxuriate in nothingness is to understand the key to Play It As It Lays.

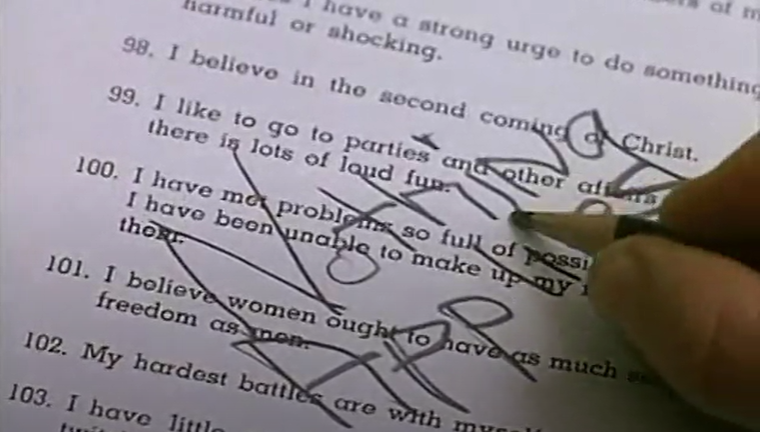

Maria is a mess, and it’s because she cares so little. We do get a sense of the one thing Maria does give a damn about: her emotionally disturbed daughter Kate, who she visits occasionally in a sanitarium. Without Kate, Maria doesn’t have much to live for, and she acts accordingly. On a first viewing, one may wonder: why is Tuesday Weld’s body language almost stilted, compared to her vivacious turn in Pretty Poison? Why does she move so slowly, with a slight smile on her face? Why do even the simplest head tilts take effort? It’s because she knows it’s not worth spending the extra energy. This makes her the most powerful person in the narrative. This minimalism powers Tuesday Weld’s performance. Almost catatonic at points, silent more often than speaking, inscrutable as to whether she’s thinking or not, it’s an excellent star turn and an example of an actress swiveling 180 degrees from the image that Hollywood may have preferred for her to take on. At one point, lying in bed in her full length long sleeved red dress, she doesn’t move at all; she looks like Sleeping Beauty or a corpse. She’s somehow luminous, with tanned dewy skin and a mop of bleached blonde hair. As the film opens, she walks methodically through a topiary garden. Her face is blank. She blinks occasionally. “I try to live in the now. I watch hummingbirds. I go for a walk during visiting hours. I see no one I used to know. But then I’m not just crazy about a lot of people. I used to ask questions and I got the answer.” We cut to the words NOTHING APPLIES, written over a personality evaluation that someone is making her take. NOTHING APPLIES might as well be the tagline for the film.

Key moments occur in what anthropologist Marc Augé would call “non-places:” transient zones where identity ceases to matter.1 Maria’s life began in a non-place: Silver Wells, Nevada (population once 28, now 0), a “town” her father remembered he owned after losing their house in Reno gambling. In a film-within-a-film clip showing one of Maria’s acting stints we see her speed through the barren LA riverbed—a body of water with no water. At a hotel—next to an airport, the ultimate nonplace—in the middle of the Mojave, Maria plainly tells her lover, “I had an abortion at 5:00 in Playa del Rey,” when he asks her what “the matter” is. In the next scene, Maria envisions a montage of images from her journey to the abortion doctor—a big “T” sign, a clinical sink, an air conditioner. These are images without their own personalities, fragments of roadside attractions and doctors’ offices. Nothingness can be perfumed with memories, but they seep out anyway. Eventually you’re just left with the abortionist’s sink.

The LA highway system, another non-place, is a character itself. Maria finds comfort there. In the book, she gets a thrill from complicated lane changes. Early in the film we see her shooting indiscriminately at rattlesnakes from the drivers’ seat. A romantic, sweeping overhead shot shows us the interstate on a cloudy day: gray, teeming with cars like insects, fog in the distance, overlaid with the audio from Maria’s call with the doctor’s office. Weld mesmerizes with her tanned skin, sharp cheekbones, bleached hair, long sleeves, peeling a hard boiled egg while driving a sports car through the tangled roads. We see her pull over to change a tire, surrounded by cars going 80 miles an hour, looking happy for the first and only time that we see her that way in the film. “I’m not going anywhere,” she tells the cop that pulls over to try to help her. “I guess you like the freeway, huh,” he says. She rambles for a bit, trying to explain what she means, and gives up.

In the iconic last lines of the novel, Maria reveals why she is able to carry on, unlike her friends who swim in circles, mired in suffering. Maria understands that both her pain and her achievements will lead her to the exact same place. The film’s final scene is so quietly bleak it’s hard to tell what’s going on, but here’s the jist: Maria’s friend B.Z. swallows a handful of pills, and instead of calling for help, Maria holds his head in her lap as he dies. Is she clinically insane? Her friends seem to think so, and that’s why we meet her in an institution when the film opens. But if we take Maria’s philosophy of life at face value—that it’s all for nothing, so you may as well do what you like—this is a logical thing to do. Everyone is heading toward the same outcome in life. What’s the difference if B.Z. gets there a bit earlier? As they lie on the bed, Maria stroking B.Z.’s hair and mumbling about canning vegetables, they luxuriate in nothingness together. It’s worth starting the film over again just to watch it through this glamorously nihilistic lens—to understand what nothing means, and keep on watching.

Footnotes

1 Marc Augé, Non-places: introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity, Le Seuil, 1992, Verso

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon