| MH Rowe |

Play it as it Lays plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 23rd, through Sunday, August 25th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Nathaniel West’s The Day of the Locust (1939), which like Joan Didion’s Play It as It Lays (1970) is a classically bleak “Hollywood novel,” ends as Didion’s later story never could: with a riot. No one could riot in Play It as It Lays. Although it is set in the unruly 1960s the violence of Play It as It Lays tends to stay inside, anesthetized or repressed. Nothing quite breaks open, breaks out, erupts, or goes wide. Didion’s protagonist, Maria Wyeth, chooses instead to stay in the “game”—a term to be understood as existentially as possible—and not break its rules, even if by the end of the novel she has clearly broken someone’s rule. As the 1972 film adaptation of Didion’s novel makes clear at the outset, by its editing alone, the only frenzy here exists in the edits. We see a montage of intercut images adding up to Maria’s memories, impressions, fantasies, and unspooling thoughts. She considers the institutionalization of her violent child, her own institutionalization at an unnamed facility, her dead marriage, and ultimately her abortion, as well as her friend BZ’s suicide. The last two items are the black holes around which the entire film orbits.

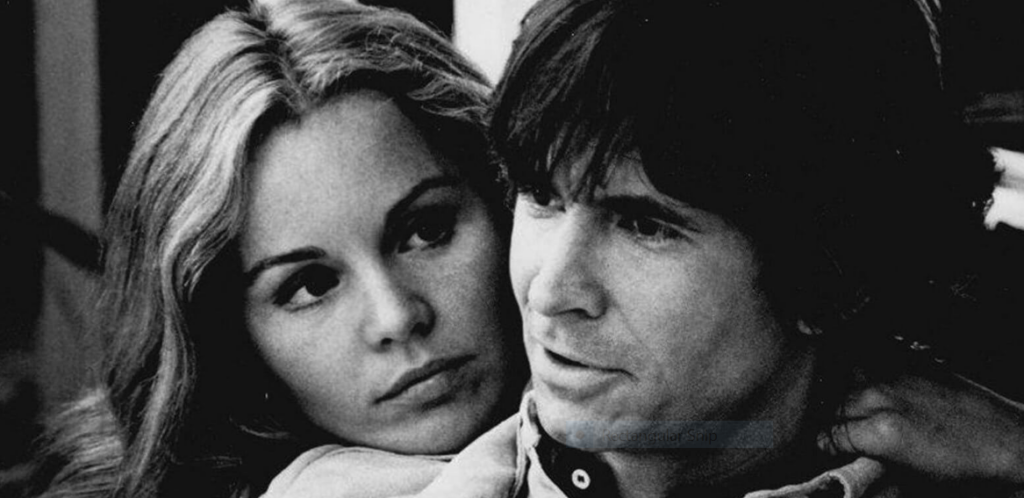

If acting is analogous to prose style, then the prose here is excellent. Tuesday Weld is ambiguously amused and amusing as Maria, in a role that might otherwise feel tiresome and frustrating. Anthony Perkins as BZ is just plain charming—and impenetrably sad. His final suicidal scene with Maria lacks any trace of melodrama yet touches a melodramatic nerve. You feel you could shriek at Maria afterward, too. It’s no riot, but it is a revelation of apocalyptic circumstance: “I know what ‘nothing’ means and keep on playing.” In voiceover, BZ asks Maria, “Why?” All she can say is “Why not?” and smile directly at the audience.

She couldn’t smile like this in the novel. The film enhances something the novel can’t show off in the same way: Maria comes alive for the camera. In footage shot by her husband Carter Lang, excerpted several times throughout the film, Maria smiles, laughs, resists giving certain personal details, and teases back and forth with Carter, who’s behind the camera. In a word, she flirts. “Is that what you want, Carter?” she says, laughing, after seeming to confess something real, a recurring fear she’s had since her mother’s death. It looks like seduction, confession, and a need to please—all molecularly bonded into one series of monologues. In other words, it looks like acting. All credit to Tuesday Weld. She feels in those scenes within scenes so sweet and yet alarmingly unlike the Maria Wyeth we see in the rest of the film, like an accomplished facsimile. Perhaps these intimate, alien appearances tell you all that Play It as It Lays wants you to understand about making movies.

One wonders, though, why Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, wanted to make this particular movie, for which they together wrote the screenplay. Of course they had written books; of course they were famous magazine journalists, essayists, observers; and understandably, of course, they wanted the money and steady health insurance of the professional screenwriters’ guild. All that’s perfectly reasonable. It would also be stupid to deny the obviousness of adapting Didion’s famous and almost instantly acclaimed novel.

Yet what electrifies in prose can feel dreary on film, with a few significant exceptions. My favorite scene aside from the ending is about ten minutes in, when Maria banters with a friendly but condescending highway cop who doesn’t seem to believe she can change a flat tire. Weld plays it a little bent and a little bubbly in that scene, exactly the right proportion. Reflecting on why she likes the freeway, she tells the cop, “It makes you feel as if they had some reason in mind when they built it, you know what I mean? I mean, it makes you feel as if you might find out the reason.” That a freeway, aptly named for its suggestion of free use for the purposes of commerce and travel, should seem not to exist for any obvious reason suits Maria and her story perfectly. It’s as if she’s already seeing the world as an apocalyptic ruin. This is a woman whose hometown in Nevada no longer exists, after all; it only had a population of 28, and her father owned the place. Her comment to the cop reads as a declaration of cracked-up hope, hope that the world might make a kind of higher sense having little to do with commerce’s bottom lines. Even if it’s the kind of sense a mirage makes.

As intelligent a production as it is, the film comes across a bit static and simultaneous, as if all the scenes add up to the same moment. The book feels more visionary than the film, more a record of human consciousness, like a modernist novel. It’s tempting to say this is Virginia Woolf in a Corvette, but Didion wasn’t a fan of Woolf. She’s terse instead, like Hemingway. Where Woolf goes lyrical, Didion goes clinical. All the interior glimpses we get in the novel of Maria, BZ, Carter, and BZ’s wife, Helene, feel like responses to a set of interviewer’s questions—interior, yes, but calculated and strategic, cooler and more objective or documentary, especially when the novel’s first-person narrator gives way to a deadpan third-person narration. The film can’t match the novel’s fragmented variety. And while Weld gives the film a sense of ambivalence and dispute, the story here amounts to something both heavy and slight without the eddies and whorls of Didion’s particular way of telling it, without its interest in Shakespeare’s Iago and tabloid death. Not that it matters too much. I like the film anyway; it reflects enough light from the brilliant novel to more or less work. Tuesday Weld and Anthony Perkins can lie around being sad forever, and I’ll probably take a look.

Early in his career, the poet W.H. Auden wrote one of the English language’s great gambling poems, “Casino.” I assume there are other great poems about gambling but have no idea at the moment what they might be. In this particularly chill and worried specimen, Auden sees clearly the snare that gamblers like Maria are in when they stay in the game: “the labyrinth is safe but endless.”

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon