| Hannah Baxter |

1917 plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, August 18th, through Tuesday, August 20th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

1917 (2019) was not the first project on which director Sam Mendes collaborated with cinematographer Roger Deakins.1 It’s not even the first war story they made together: that would be Jarhead (2005), a film that makes an interesting counterpoint to 1917. The latter film follows Will Schofield, a young English soldier who, along with his friend Tom Blake, must deliver a letter to Colonel Mackenzie, the commanding officer of another regiment, and stop him from leading his unit into a German trap. We dog Schofield and Blake as they traverse No Man’s Land and a maze of German fortifications. Then we tail Schofield as he continues alone, crossing a fallen bridge and the ruins of a French village, dodging bullets, and surviving a plunge into a fast-moving river. We experience these events as a single, fluid sequence, because the film is presented as one continuous shot.

Here’s what Deakins had to say about Mendes’ ambitious concept:

When I saw “This is envisioned as a single shot” written across the top of the script, I was a bit skeptical, I have to say. I thought it might come across as a gimmick. But then I read the script and realized what Sam was intending by the one-shot idea. He wanted the film to be immersive, to make the audience feel the urgency of the soldiers’ journey by staying with them every step of the way.2

Note that Deakins’ skepticism related to audience reception, and not technical feasibility! He must love a challenge.

Deakins’ first move was to meet with the Arri camera company. He needed a digital camera that was small and light enough that camera operators could carry it around, hand it back and forth, and mount it on booms and cranes, all while it was rolling. Arri ultimately provided Deakins with a prototype of a brand-new camera two months before filming started, and two more a week beforehand.

Preproduction included several months of rehearsals. Long takes would be stitched together seamlessly, so there would be no cutting away from the actors. The camera would travel with them, ahead, behind, or overhead. This meant the sets had to match the actors’ movements, and not the other way around.

Roger Deakins (left) and Sam Mendes (right) on the set of 1917. In post-production, the structure behind them was replaced with a burning cathedral using CGI. The LED lights on the structure provided lighting for nighttime scenes in the ruined village. The LEDs were programmed to grow dimmer and brighter to imitate a real fire.

“We were on open fields in the middle of nowhere, walking it out and marking what happened where with poles,” Mendes said of those early rehearsals.

Until we had done that, we couldn’t construct any sets. We couldn’t build a trench until we knew exactly at what point the trench had to turn left, turn right—where the scenes would happen within it. Everything started with the empty field and the script. The big difference was that the actors were with the crew and me from the first day of prep, and everything was built around their journey. It was the polar opposite of normal movies, where you prep for six months and then the actors arrive and you say, “These are the sets.”3

Every set was purpose-built for the film: half a mile of trenches, a downed bridge, a ruined village, a barn and an empty farmhouse. The single-shot concept dictated Deakins’ lighting choices, too. He couldn’t light the set with the usual gear, because the moving camera would catch the lights in the frame. They would have to shoot in natural light only, which in turn meant filming only during cloudy weather to maintain a consistent look from take to take. When the sun came out during production, they’d stop filming and rehearsed some more.

George MacKay, who plays Schofield, was relatively unfamiliar to audiences when he was cast, effectively making his character a kind of blank slate that audiences can readily empathize with. In fact, it’s so easy to identify with Schofield that watching him pursue his quest through mud and water and fire feels like playing a video game with the soldier as our avatar. We see the battlefield, the scarred landscape, the mission itself through his eyes. And we see some incredible things.

That’s particularly the case in the second act. Schofield loses consciousness at one point and the scene fades to black. When he wakes up, night has fallen. While the daytime scenes include some surreal imagery—the astonishing devastation of No Man’s Land, for example, where a tank lies upended in a shell hole like a beached whale–the daylit world is mostly recognizable as the one we live in. In contrast, Mendes wanted the second act to feel “dreamlike,”4 though nightmarish would be another apt word for it. Schofield runs through a ruined village lit up like a carnival by flares and a burning cathedral. He hides briefly in a cellar where he finds a young woman caring for an orphaned baby; they converse haltingly in a mix of French and English. Later, pursued by half-glimpsed enemies, he leaps into a river in desperation. Dawn finds him carried away by the water, so tired that he falls asleep clinging to a floating log and only wakes up when he slips back underwater. He crawls out of the river over a pileup of waterlogged corpses and stumbles upon a grove where dozens of soldiers sit among the trees listening to one of their own singing an American folk song.

Schofield (left, played by George Mackay) and Blake (right, played by Dean-Charles Chapman) approach an abandoned farm.

Schofield has no one to talk to about what he’s seeing, and the fact that these scenes pass without commentary or explanation underscores the dreamlike quality that Mendes was after. In fact, the scenes that do have dialogue are often less moving than those without. Consider Schofield’s encounter with Captain Smith, who gives him a lift partway to his destination. Smith learns that Schofield witnessed Blake’s death just minutes before and advises him, “It doesn’t do to dwell on it.” This is the British “stiff upper lip” taken to a point that feels borderline parodic.

Smith also tells Schofield to make sure there are witnesses when he hands the warning letter to Mackenzie, just in case the colonel decides to ignore his orders. This bit of foreshadowing suggests that the encounter with Mackenzie will be its own kind of skirmish–a battle of wills or wits, perhaps. If 1917 really were a video game, outmaneuvering the colonel would be the final level. When presented with the letter, though, Mackenzie calls off the attack immediately, and we get what passes for a happy ending in a First World War movie: a disaster deferred. Mackenzie also offers Schofield his thoughts on how the war’s outcome will finally be determined: by the “last man standing.” Because the film is fairly light on dialogue overall, Schofield’s conversations with supporting characters are given extra weight—but clichéd phrases like Mackenzie’s and Smith’s tend to undermine the impact of those conversations.

1917 gives us supporting characters’ brief takes on the First World War, but the film itself doesn’t have a viewpoint about the war. This may be what led critics to judge it harshly as “prettified” and “sanitized.”5 No doubt some viewers would prefer that Mendes paint a fuller picture of this catastrophic conflict. It’s true that the film shows us only a handful of dead out of the nine million or more soldiers who died, a few rats just living their best rodent lives in an abandoned German dugout, an orderly field hospital with calm staff and patients whose injuries the camera glides past. Schofield and Blake say that they are hungry, but when Schofield empties out his knapsack for the Frenchwoman he meets, the rations he gives her look pretty generous.

Then again, when we go into a movie looking to have our opinion confirmed (for example, the opinion that the First World War was as hellish as it was wasteful), and when we judge the work in front of us by how closely it matches that opinion, we’re not really open to what the movie has to tell us. We may even miss the point. Because while the many and varied perils of the Western Front form the gauntlet that Schofield must pass through (or, returning to the video game comparison, the levels he has to beat), 1917 is not about how terrible the First World War was. It’s about Schofield and the way he loses himself in his quest, shedding fear, pain, and ego as he goes.1917 is about war in the same way that the documentary Touching the Void (2003) is about mountain climbing. In reality, both of these films are about human beings in extremis and what they’re capable of.

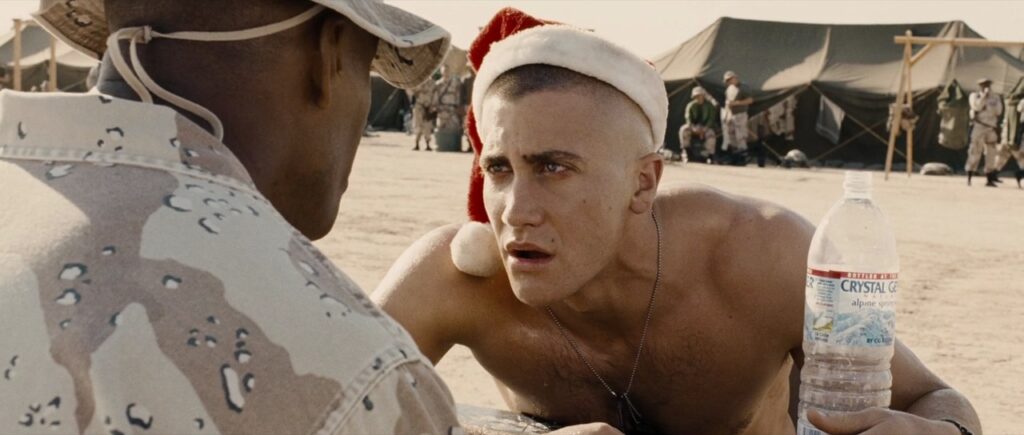

Swoff is so done with Sykes RN. The feeling is mutual.

The same could be said of Jarhead, which Mendes directed based on a Gulf War memoir by a former marine. The main character, Swoff (Jake Gyllenhaal, admirably committing to a seriously unpalatable role), along with the other young men in his unit, are deployed to Saudi Arabia, where they pine both for combat and for their wives and girlfriends, while getting into ever-more-serious trouble. With a few exceptions, the men of this unit don’t come off particularly well. They’re amped-up frat boys, all pranks and bluster and crude innuendo. They embarrass their long-suffering boss, Staff Sergeant Sykes (Jamie Foxx, playing the only grown-up for miles around), in front of the news media. They buy a giant container of illicit booze and party naked in Santa hats. They make two scorpions fight, and they get really, really into it. In 1917, Schofield goes to lengths to avoid violence. Swoff, on the other hand, can’t wait to try out his new sniper rifle.

Where 1917 is all rich browns and greens against that cloudy sky, Deakins made Jarhead look desaturated and gritty. Sunlight washes away color, making the landscape as monotonous as the Marines’ tour of duty. Months pass without their unit seeing any action, and finally, it’s boredom—combined with the extreme heat—that drives Swoff to distraction. He loses control completely, threatening another Marine with a loaded weapon, then changing his mind and encouraging the other soldier to kill him instead.

Schofield and Swoff are a study in contrasts–Schofield stoic and duty-bound, Swoff selfish and surprisingly undisciplined considering his branch of the armed forces. Pushed to his breaking point, Schofield summons the strength to fulfill his mission. Pushed to his breaking point, Swoff…breaks. Later, at the urging of another soldier, Swoff apologizes to the friend he threatened. Just as he starts to get emotional, there’s gunfire in the distance—the first they’ve heard since training–like the universe is thwarting Swoff’s chance to redeem himself.

There is one point of commonality between the two soldiers, though. At the end of 1917, Schofield takes an ill-advised shortcut by leaving the trench and running across the battlefield. He gets knocked down by two soldiers going “over the top,” picks himself up, and keeps running.6 Similarly, when Swoff first sees combat, he stands seemingly stunned in the line of fire until another soldier hauls him into a ditch where the others are sheltering. Both Schofield and Swoff have entered an altered state of mind, a kind of trance, in another example of how people can react to extreme circumstances.

Swoff survives the Gulf War; we don’t know what happens to Schofield. We leave him sitting under a tree, just as we found him at the beginning of the movie. 1917 is more plot- than character-driven, so it doesn’t drop any hints as to how the events of the past day have changed him (and we can only hope that Swoff has changed for the better). If 1917 is a game, we’ve finished it. And as for the horrors of war, maybe it doesn’t do to dwell on them.

Footnotes

1 That’s Sir Roger Deakins, CBE, to me and you.

2 Rachael Bosley, “Lives Under Siege: The Goldfinch and 1917,” American Cinematographer, January 13, 2020.

3 Benjamin Lindsay, “Sam Mendes and George MacKay on How ‘1917’ Was Built Around Its Actors—Literally,” Backstage, May 14, 2020.

4 Bonus feature, 1917, directed by Sam Mendes (2019, Universal), DVD.

5 Richard Brody, “The Beauty of Sam Mendes’ 1917 Comes at a Cost,” The New Yorker, January 7, 2020; Manohla Dargis, “Paths of Technical Glory,” The New York Times, December 24, 2019.

6 It was purely accidental that extras ran into Mackay, but no one was seriously hurt, and the take made it into the movie.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon