| Hannah Baxter |

The Watermelon Woman plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 9th, through Sunday, August 11th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

The Watermelon Woman (1996) is a movie about making a movie about movies—the very definition of meta. The main character, Cheryl, played by writer-director Cheryl Dunye, is steeped in moving pictures. She supports herself videotaping weddings and working in a video rental store alongside her friend Tamara, but she really wants to be a filmmaker. In her spare time, she watches movies from the 1930s and 1940s, particularly attentive to Black actors who were relegated to secondary roles, and who were often uncredited. Cheryl becomes intrigued by one actor in a film by director Martha Page called Plantation Memories; the actor in question is billed only as “the watermelon woman.” Her identity becomes the mystery at the center of this playful story of friendship, love, and history that lies hidden just under the surface of what’s made public.

Plantation Memories is not a real movie. Martha Page was not a film director. The watermelon woman never existed, and The Watermelon Woman is not actually a documentary. But you could be forgiven for being confused on all of these points, because Dunye conjured up a fascinating biography for the watermelon woman (“real” name: Fae Richards). Along with photographer Zoe Leonard, she also created a convincing photo and video archive featuring movie stills, glamor shots, film clips, and newsreel footage of Richards.

On a fundamental level, The Watermelon Woman is a film noir. It follows an aspiring filmmaker instead of, say, a private investigator, but like many detective stories, it centers around a disappearance—the disappearance of an artist from collective memory. Cheryl works her case like a private eye who carries a video camera instead of a handgun. She pounds the pavement, gathering clues from colorful characters. She relies on instinct and luck to uncover a story that ends up being bigger than she anticipated; she even meets a femme fatale—all noirish tropes.

Cheryl wants to turn her search into a documentary, and she videotapes interviews with family and friends, film buffs, and even the cultural critic Camille Paglia. Paglia plays a hilariously oblivious version of herself whose answer to every question seems to circle back to her Italian-American heritage. Cheryl also does person-on-the-street interviews; a trio of film students tell her, “If [the watermelon woman is] in anything after 1960, don’t ask us. We haven’t covered women in the Blaxploitation movement yet.”

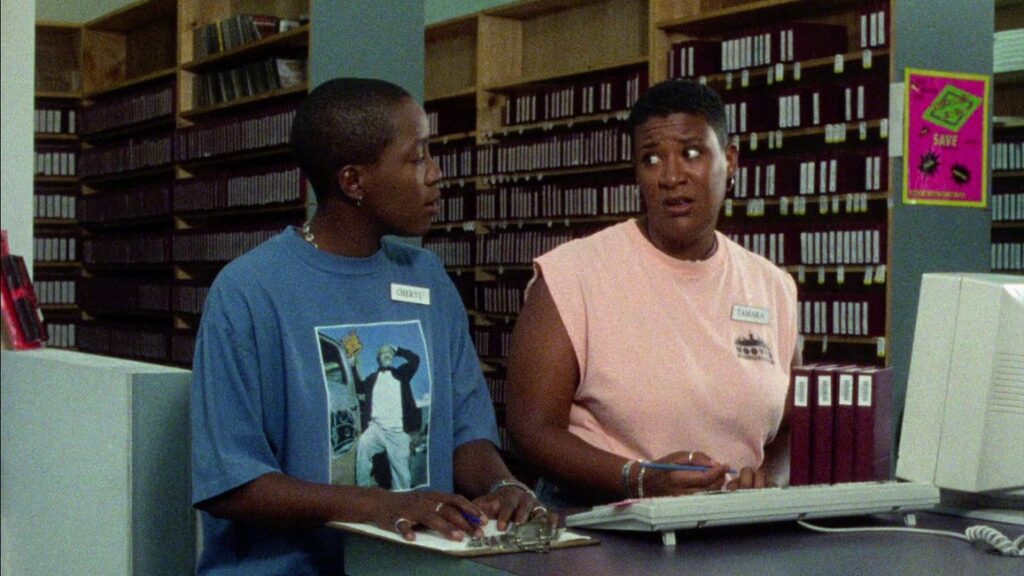

Cheryl (left) and Tamara (right; played indelibly by Valarie Walker) disagree about how much ogling is too much.

As her investigation progresses, Cheryl’s own life gets a little more complicated. Her friendship with Tamara can be antagonistic at times: scenes reminiscent of Clerks find the two behind the counter at the video rental store, where Tamara ribs Cheryl about her documentary project and her approach to dating. Cheryl, in turn, teases her friend, “Tamara, why are you always constantly clocking women?” “We’re lesbians, remember, Cheryl?” Tamara replies. “We’re into female-to-female attraction.” When Cheryl starts dating flirtatious Diana, who is white, Tamara takes a dislike to Diana. Cheryl’s new romance drives a wedge between the two friends.

The Watermelon Woman treats the shifting grounds of friendships and romantic relationships with subtlety, much as it does the complexities of race, sexuality, age, and culture. When Cheryl learns that Richards was involved with her director, Page, she is delighted. She speaks to the camera: “Can you believe it? Fae’s a sapphic sister!” On the other hand, she’s not quite sure what to make of the fact that Page was white, or of Richards’ friendships with white patrons of the clubs where she sang after her career in film ended. “Fae hung with the ofays?” she muses. Her pursuit of Richards’ story takes her to the Center for Lesbian Information and Technology (CLIT)—a loving send-up of the Lesbian Herstory Archives—for a very funny conversation with a volunteer archivist.

“We received a very generous gift from the Hysteria Foundation, but they wanted it to be used exclusively for African-American lesbians,” says the archivist, who’s played by a scene-stealing Sarah Schulman, a novelist and repeat collaborator with Dunye. “So if we have any photographs that there are white people in, we just cross them out.”

Cheryl finds a treasure trove of material about Fae Richards, but the archivist kicks her out before she and her crew can document it. “This is a safe space!” she declares. Anyone who has spent time in academia will enjoy the way this film pokes fun at the very institutions and environments that made it possible: it’s sharp, but it’s never mean-spirited. The Watermelon Woman is a mockumentary in the best possible way. (Dunye, many of whose works meld reality and fiction in this way, called the movie a “Dunyementary.”)

Cheryl ends up tracking down Fae Richards’ partner of many years, a woman named June Walker. However, before Cheryl can interview her, Walker is admitted to the hospital. She writes Cheryl a letter from her hospital bed encouraging her to tell Richards’ story. The documentary that Cheryl makes then plays over the end credits of The Watermelon Woman.

For all the ambition of its concept and execution, The Watermelon Woman is a bootstrappy production that cost just over $300,000 to make. Dunye raised the money herself—selling the fake Fae Richards archive, for one thing. Her partner, media scholar Alexandra Juhasz, who at the time taught film at Swarthmore College, produced the film. Juhasz got her students involved, telling Dunye, “We’ll call it a class or extra credit.” Juhasz herself appears in the ersatz scenes from Plantation Memories.

“That’s where it started, with a lot of students and people doing it for free,” Dunye told Slate. “I applied for grants, little grants, bigger grants, and then the biggest grant at that time was the [National Endowment for the Arts]. I sent my little proposal in, and I got it, $31,500.” The Watermelon Woman ended up getting the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in trouble with certain members of Congress, who objected to its sex scene. One Michigan Republican memorably wrote that this and several other LGBTQ-themed films amounted to “a veritable ‘taxpayer-funded peep show.’” Tamara would probably approve; she secretly orders titles like Bald Black Ballbusters under the pretense that they are video store customer requests.

Because of Walker’s poor health, Cheryl misses the chance for a real resolution to Richards’ story. But the real work of the movie has been completed. If its bones are noir, The Watermelon Woman is fleshed out with the characters we meet.

The Dude is in over his head at porn magnate Jackie Treehorn’s party.

In that sense, The Watermelon Woman is a cousin to The Big Lebowski (1998). A movie that was released to the collective “meh” of critics everywhere, The Big Lebowski has become a cultural touchstone, launching a thousand midnight showings and a quasi-religion, too. But what is the movie about? It’s weirdly hard to explain, even if you’ve seen it 20 times. Cowriter-codirector Joel Coen said he and Ethan Coen deliberately made the plot “hopelessly complex” and also “ultimately unimportant.” Indeed, like The Watermelon Woman, The Big Lebowski is chiefly concerned with introducing you to people and places that you will adore. Compare the Dude’s nemesis, fellow bowler Jesus Quintana, with the surly university librarian (played by writer David Rakoff) that Cheryl has to contend with. Or place “Big” Jeffrey Lebowski’s personal assistant, Brandt (played with gusto by Philip Seymour Hoffman), side-by-side with Cheryl’s boss, Bob. A stickler for proper video rental protocol, he asks a new employee, “Are you learning the Bob system?”

Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers (2005), too, is a character-driven story built on a noir substructure. The protagonist, Don Johnston (emphasis on the “t”), an aging Lothario, habitually sleeps on his couch, maybe because of all the time he’s spent on the outs with his various girlfriends. Like Tamara—who can’t help but ogle the audience of a feminist poetry slam that she’s videotaping—Don genuinely loves women. Yet perhaps because of an inability to commit to just one, he always ends up alone. When he gets an anonymous letter from a past flame informing him that he has a son, his best friend, Winston, insists on tracking down Don’s exes and cajoles him into visiting them to “look for clues.” And so, like Cheryl and the Dude, Don sets out (reluctantly) to solve a mystery.

Don is played by Bill Murray in what I like to think of as his blue period, also comprising Rushmore (1998) and Lost in Translation (2003). Look up “melancholy” in the dictionary and you’ll find a picture of Don sitting in the rain at an ex’s graveside. Still, like life itself, Broken Flowers is, oftentimes, a comedy. One running joke that’s gotten funnier over time is that Don made his fortune in “computers.” He never gets any more specific. “Computers! That’s gotta be a lucrative field,” says Ron, who’s married to Don’s ex Dora. He’s delightfully square, like the partygoer in The Graduate who famously has “just one word” for Benjamin.

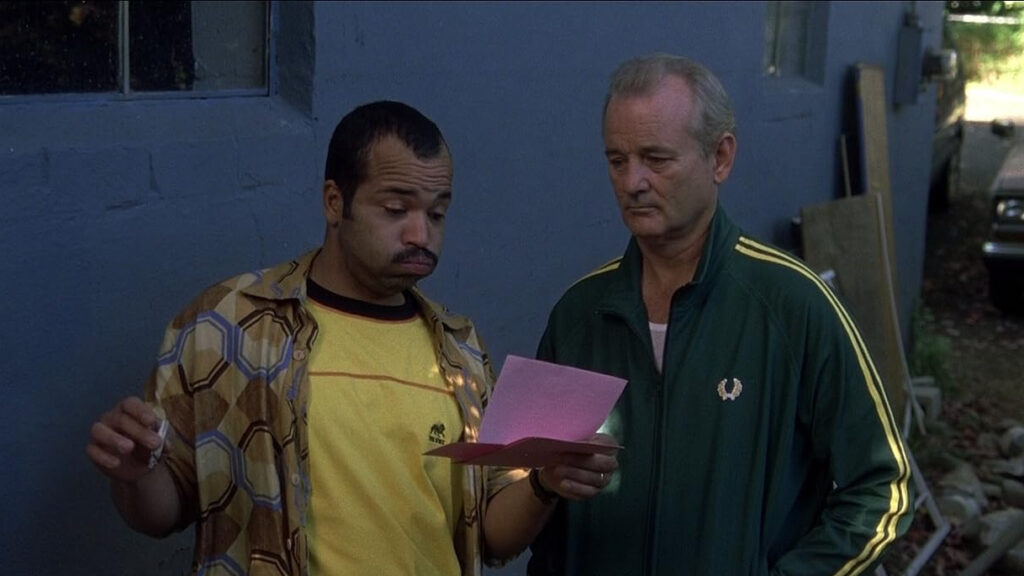

Winston (left, played by Jeffrey Wright) examines Don’s anonymous letter with the aid of some “assorted herbs.” Cannabis use is another point of commonality between these three movies.

Don’s lucrative field is immaterial to his investigation, which, compared with Cheryl’s or the Dude’s, is extremely straightforward. A surprising portion of the 101 minutes’ runtime is taken up with scenes of wooded highway margins viewed from rental cars. (This probably portrays the boredom-to-action ratio of a real investigation more accurately than the dramarama of noir classics like Chinatown or The Maltese Falcon.) But then you meet four women from Don’s past, played with vibrancy by Sharon Stone, with repressed emotion by Frances Conroy, with acuity by Jessica Lange, and with simmering hostility by Tilda Swinton. Layer over all of this Murray’s understated performance,1 and you have a substantive movie: ruminative, deeply felt, and, like The Watermelon Woman, inconclusive. Don never finds out which of his exes raised his son—if he has a son at all.

In a DVD extra entitled “Farmhouse,” Jarmusch says,

[S]uch a valuable part of life to me…is randomness. And just chance and coincidence. It’s really these things guide our lives…. You know, you can plan things out as much as you want, but the most beautiful, deep things in our lives are not rational, they’re usually emotional, or they’re connections with other people. And those things are very mysterious. So those things, they add up to a whole fabric of life, for me. […] [T]hings don’t happen in a rational way, they happen in an emotional way, or a random way, or by molecules in the universe moving in a way we don’t control, you know?

He could be talking about the case of mistaken identity that sets the plot of The Big Lebowski in motion. Or about the parallels that Cheryl discovers between her life and that of Fae Richards. Here’s a coincidence: Broken Flowers was originally titled Dead Flowers, which is also the name of the song that plays over the end credits of The Big Lebowski. Here’s another: The Watermelon Woman and The Big Lebowski are both among the 875 works (including shorts, newsreels, music videos, and other moving pictures in addition to full-length features) that have been admitted into the National Film Registry for their “cultural, historic or aesthetic significance.”

If there’s something that, like the Dude’s rug, really ties these three movies together, it’s their slacker approach to noir. The protagonists are at loose ends when they’re presented with the puzzles that get the movies rolling (Don’s arrives conveniently in the mail). They try to solve these puzzles in part because they have time on their hands. Along the way, they get willingly distracted by sex, drugs, and killer soundtracks. And if they end up pretty much where they started? They’re comfortable with that.

Footnotes

1The funniest thing Murray does in this movie is eat carrots. Incidentally, you could say the same of his performance in Rushmore.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon