| Cole Seidl |

One Cut of the Dead plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, July 7th, through Tuesday, July 9th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Shinichiro Ueda’s One Cut of the Dead has been incredibly, yet quietly, influential since its initial release in Japan in 2017. It has spawned a small independent film movement in Japan known as “nagamawashi” films (or “long take” films) which aim to exploit the inherent aesthetic tensions of a time-based medium like film by minimizing the number of edits the audience is aware of. This has resulted in at least one other contemporary cult-classic, Junta Yamaguchi’s Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes.1 Ueda’s film was re-made by Oscar winner Michel Hazanavicius as Final Cut in 2022. It spawned two (middling) sequels. Most importantly, it has inspired endless conversations and arguments between cinephiles who have been left both baffled and delighted by its unique characteristics.

One Cut of the Dead is one of the few films that truly benefits from the ignorance of its audience members. If it is still possible, at this point, to learn nothing about the film before seeing it, commit to this ignorance and return to reading about the film at a later date.

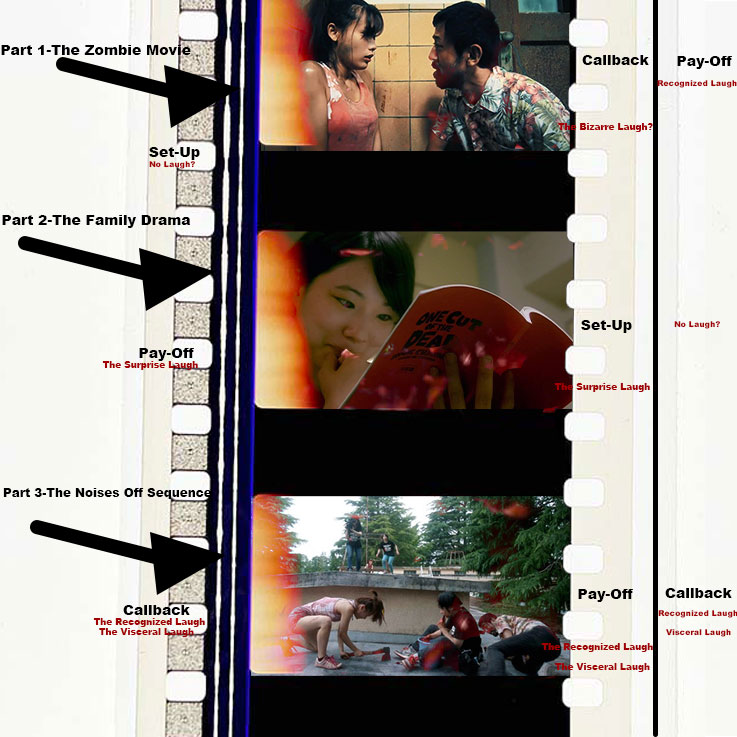

The single characteristic of the film that most people find themselves charmed or frustrated by is its basic structure. It can be roughly divided into thirds: Part 1 – The Zombie Film, Part 2 – The Family Drama, Part 3 – The Noises Off Sequence.2 These three components are quite distinctly separated from each other, but also equally essential in considering the film’s overall construction as a comedy. Or, perhaps even as a single long-form gag.

In his book Why Is That So Funny: A Practical Exploration of Physical Comedy,3 John Wright outlines the 4 different kinds of laughter a physical gag can provoke from an audience member: The Recognized Laugh, The Visceral Laugh, The Bizarre Laugh, and The Surprise Laugh. It is not difficult to take one’s favorite gags in film history and to categorize them as such. The Recognized Laugh comes from our personal connection to the gag, a recognition that what we see rings true.4 The Bizarre Laugh is the counterpoint to the recognized laugh.5 Our laughter is an incredulous response to something we believe we could not possibly understand. The Visceral Laugh is the one most associated with slapstick comedy, primarily consisting of pratfalls.6 The laughter is provoked by our sense of empathy (or possibly schadenfreude) when we see someone experience sudden pain or discomfort. Finally, there is The Surprise Laugh, which exists primarily as a subversion of the clearly outlined expectations of the audience.7 These categories, it should be noted according to Wright, are not exclusionary and it is possible to laugh at all four provocations simultaneously.

Part of the pleasure of One Cut of the Dead is the discovery of just what, exactly, it even is. It largely spread among American audiences on Shudder, the streaming service for horror films. It proved to be quite successful among horror fans, despite the fact that only about a third of the film could be classified as a horror film, and that third is profoundly without any real scares. However, it seems to have charmed horror film lovers because, by the end, it is a comedy about horror films.

The most fruitful genre exploration of this particular film is through the lens of comedy, and also, as a single gag. Gag structure has been locked down since long before the advent of cinema itself, most clearly in the vaudeville era. The simple structure of a gag is Set-Up, Pay-Off, and Callback. According to conventional comedy wisdom, the Set-Up should establish some clear rules or truths. The Pay-Off (or punchline) then subverts these rules in some way. An obvious example of this would be the Emo Phillips joke “I love going down to the schoolyard to watch all the kids jump and scream… because they don’t know I’m using blanks.” The set-up gives us something that is a statement but not a joke. It’s a statement we could accept as true. The punch line re-orients and forces us to confront our assumptions about the “truth” of the initial statement. The harsh juxtaposition of the two sections then create humor. In the Emo Phillips joke, it elicits a Surprise Laugh. If Phillips were to make another joke about attempting to commit suicide, describing the moment he presses the barrel of a gun to his temple, then, slowly, pulls the trigger, leading the audience to ruefully realize he was using his “schoolyard gun,” this would be a Callback. He would be giving us an entirely new joke, however, the joke would work through its intertextual relationship with a joke we are already familiar with.

With this vaudevillian gag structure in mind, it becomes clear that One Cut of the Dead has a structure that can be used to play its basic gag forward, backward, and inside out—like some sort of comedy-jazz. The first, and in my opinion least effective, version of this gag is the chronological order of the film. We get Part 1: The Zombie Movie as our set-up. Throughout this chunk of the film we are forced to accept the “truth” that we are watching an ambitious amateur production that has not succeeded in its ambitions. There may be some pleasures to find, but most people during this section of the film question why they have heard such great things. The set-up works as a statement, but not a joke. Then we move onward to Part 2: The Family Drama. This is functions as an Emo Phillips-esque punchline, where we are forced to recontextualize everything that came before it. Any humor from this punchline comes from The Surprise Laugh of having our assumptions failing us so profoundly. Finally, Part 3: The Noises Off Sequence happens, and this provides the most immediate pleasure. Within the film’s broader gag-structure, this is merely a Callback to the initial joke. We are now viewing the set-up and the payoff simultaneously, and understand both with full context. This is the section that allows for the greatest succession of laughs and the widest variety of laughter types. We get plenty of Visceral Laughs with people falling down, vomiting, experiencing explosive diarrhea, or simply dealing with profound confusion. We get several smaller-scale Surprise Laughs as we start to see the exact reason for some of the amateurish moments from the initial set-up. We also get many Recognized Laughs. I suspect this aspect is why the film has developed such a strong cult following. Most of those who love the film have made (or attempted to make) their own films at some point in their life, or participated in community theater productions. They have worked in a scrappy ragtag way to attempt an ambitious performance and seen firsthand how ridiculous theater and film production looks behind the scenes.

We can, however, completely re-organize the structure of the gag within the film and get a postmodern representation of a vaudevillian gag. If we look at Part 2: The Family Drama as the set-up (which shouldn’t be difficult, as it is first within the film’s chronology and contains the vast majority of the exposition.), then we can look at Part 3: The Noises Off Sequence as the pay-off… in which hijinks ensue from the impossible production demands put upon our ragtag film crew. This would allow us to look at Part 1: The Zombie Movie as a callback. Part 3 shows the amazing ends this crew goes to as a means of pulling off the feat of a single-take zombie film. The callback shows us the incredibly middling film that results from this effort. This is funny and existentially horrifying to many people of artistic temperament. This also leads to the film’s ultimate humanity. The end result of the film does not matter; there is a beauty in the communal act of film production and the herculean efforts of each individual involved. Allowing the bitter callback to be viewed first re-shuffles our gag structure, and allows the final moments to rest on poignancy rather than cynicism.

One Cut of the Dead has found a strong cult following in the years since it was released. I suspect its postmodern gag structure allows for a great number of ways to experience the film, and to approach its myriad of laugh types from several perspectives. Hopefully, audiences will keep discovering new ways to engage with it for years to come.

Footnotes

1 Which has been consistently described as a no-budget, more fun version of Tenet.

2 If you love this section of the film, I would highly recommend that you investigate Peter Bogdanovich’s 1992 film Noises Off, which follows all the mishaps of a Broadway stage production both from an audience perspective, and from backstage. Much of the humor is derived by how the backstage drama transforms the form and content of the actions onstage.

3 John Wright, Why Is That So Funny?: A Practical Exploration of Physical Comedy, London: Nick Hern Books, 2016.

4 An example of The Recognized Laugh from a popular Vine Video.

5 An example of The Bizarre Laugh from a short film by 5 Second Films.

6 An example of The Visceral Laugh from Kelsey Grammar’s fall during a public lecture.

7 An example of the Surprise Laugh from the film Top Secret.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon