| Dan Howard |

The Player plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, June 9th through Tuesday, June 11th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

From 1977 to 1990, Robert Altman’s career as a filmmaker began to dwindle, teetering from decent-sized ups to major downs. Every other film coming from Altman was received with mixed to lackluster reviews, with some exceptions like 3 Women (1977), Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982) and Secret Honor (1984). His commercial appeal was rapidly diminishing. Despite Altman’s 1990 Van Gogh film, Vincent & Theo, receiving divided reviews, it prompted the CEO of Avenue Pictures, Cary Brokaw, to reach out to Altman about adapting Michael Tolkin’s 1988 novel of the same name into a feature film. This adaptation ultimately became one of Altman’s finest works and gave him the boost he needed to reach new heights in his career.

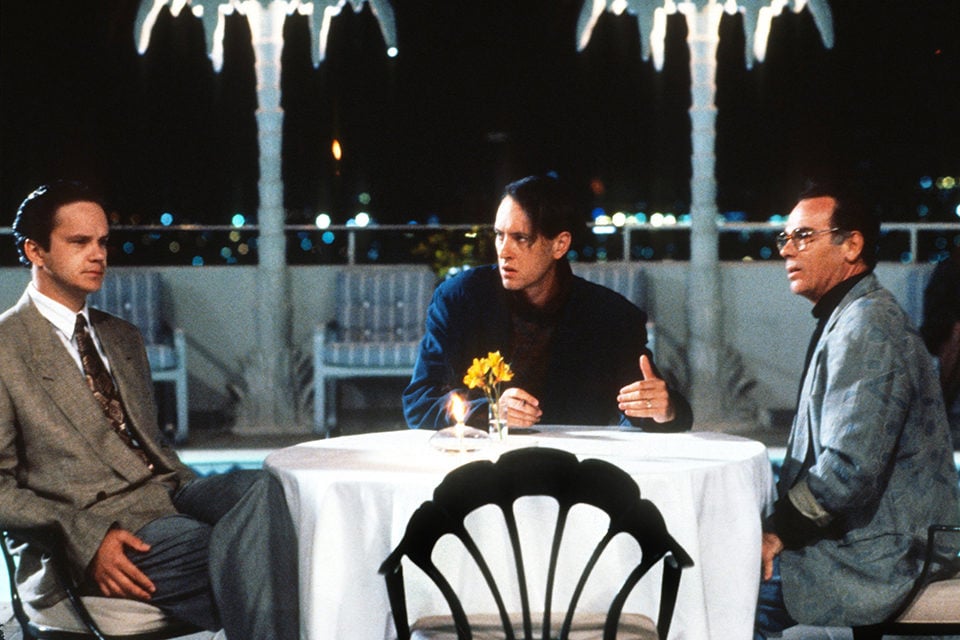

The Player follows Hollywood producer, Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins), who believes he is being stalked by a writer that he blew off a couple weeks prior, leaving Griffin postcards with intimidating messages. When Griffin tracks down the writer, David Kahane (Vincent D’Onofrio), at a screening of Bicycle Thieves, Kahane gets hostile. Mill retaliates and kills Kahane by drowning him in a puddle of water. While wrestling with the guilt of Kahane’s death, Mill attempts to go on like nothing happened while sparking a romance with Kahane’s girlfriend, June Gudmundsdottir (Greta Scacchi). When the postcards resurface and the police begin their investigation, Griffin Mill desperately attempts to cling to his position of power.

Michael Tolkin had initially written The Player to distance himself from Hollywood, painting these portraits of film industry folks as the self-important, conceited, pompous individuals that are being displayed throughout the film adaptation: Producers who think of themselves as Gods because they make movies happen while everyone pines to them to get funding and distribution. Directors pitching films with Oscar-bait plots and who are adamant about keeping their vision only to cave with one negative audience screening. The image-conscious actors. A stereotypical-looking writer who may be more pretentious than he realizes. Tolkin had clearly had enough and seemingly just didn’t care if he ever worked in Hollywood again. He had no intention of adapting the novel into a film himself. Hollywood is notorious for making movies about their own industry, but how often do you get to call Hollywood out on its hypocrisies? Robert Altman couldn’t resist this golden opportunity, and you can see his passion and determination for making The Player a true work of art with not only one of the greatest opening scenes of any film, but one of the greatest long takes in cinema history. It tracks everyone moving through the studio lot, in and out of the offices, discussing their day-to-day lives making movies and creatively referencing other films with great long takes like Touch of Evil. The excitement for cinema and that the never-ending battle of passion and business is present from the start.

It’s safe to say that Altman and Tolkin both had their fair share of experiences with producers throughout their careers. Naturally, not all of them were good. However, it feels like the conception of Griffin Mill’s character is Tolkin’s and Altman’s attempt at a more compassionate look on a Producer’s thoughts and feelings, exploring Altman’s and Tolkin’s process when their character is faced with a heinous crime like murder and showing that while a lot of big producers may have that slimy personality on the surface, they are still human and capable of guilt and remorse like the rest of us. In contrast, we also see the internal conflict between Griffin Mill the person and Griffin Mill the producer, observing the subtext of his demeanor before, during, and after murdering Kahane. This subtext is perfectly incorporated by implying that a lot of Mill’s actions reflect the actions and attitudes of a lot of other Hollywood individuals Altman and Tolkin have come across. For example, as Mill initially investigates Kahane as the prime suspect behind the threatening postcards, he goes to Kahane’s home only to find his girlfriend, June, at the residence alone and calls her from right outside her home, staring at her through the window like a creep. One could see this as Hollywood thinking they can simply insert themselves into people’s private lives when it will benefit them the most. In Mill’s case, he may think, due to his circumstances and position, that he has the right to. Fast forward to Mill tracking down Kahane at a screening of Bicycle Thieves and striking up a casual conversation afterwards. When Kahane calls him out, you can see Mill’s insecurities start to bubble up when Kahane accuses him of being a useless person outside of his producer position, yelling to Mill, “I can write! What can you do?” Mill, at this point, is pushed to what can only be described as a heat-of-the-moment killing. I can imagine Mill was trying to kill his insecurities of not having any actual talent or being useless, letting out that unresolved anger. You can see any sense of his Hollywood life vanish from his eyes upon realizing what he’s done.

Mill naturally tries to go about his life like nothing happened, playing dumb when anyone asks about him going to see Kahane after its reported Kahane’s body was found. The dark deed continues to affect him, even being constantly surrounded by movie posters with stories about murder and people paying for their crimes, which only proves how obsessed Hollywood is with murder: Highly Dangerous, Murder In the Big House, Prison Break, etc. Mill is prompted to reach out to June once again looking for some comfort in how kind she was to him but ends up sparking a romance. Pretty messed up, right? Mill takes Kahane’s life then he takes his girl. However, it plays well into the observation the film explores into what Hollywood can really think about writers. David Kahane, brilliantly portrayed by Vincent D’Onofrio, for instance. He’s depicted as a typical struggling writer – someone producers would just brush off without second thought like Mill originally had. He is looked down upon because his work isn’t worth anything to the studios. Mill even jokes in a meeting with his fellow producers how they should just get rid of the directors, writers, and actors altogether. A joke that just made people roll their eyes back then, but it feels a lot more relevant today with A.I. threatening to take over Hollywood. Makes you question if Altman and Tolkin ever even considered something like A.I. as a possibility in their industry.

The sad truth is that the industry has seemed to always downplay art films simply because they “don’t make money.” Even The Player initially had trouble securing enough funds for the completion of the film, but of course the studios were all clamoring for distribution rights. Certainly, this says a lot about how certain studios like to think. In the same producers meeting where Mills cracks the joke about cutting out directors and writers, there is a discussion about when the last time anyone in the room went to see a movie, Mill mentions seeing Bicycle Thieves the night before. One woman says how much she loves the film while another guy comments: “That was an art film. That doesn’t count.” Despite this mindset, Mill can’t help but be intrigued by director Tom Oakley’s (Richard E. Grant) film pitch that includes a very creative description of the opening scene and not having a typical “Hollywood ending” that Tom does not want to compromise on. Even the idea of “No stars. Just talent” throws off the other big wigs. After all, in their minds if there are no major stars, how will the film sell? Trying to see Tom fight for the film he wants to make is refreshing. You can tell he doesn’t let his guard down the entire time when getting his film off the ground, but he knows the temptation of giving in to the “Hollywood ending” never goes away. How many times have we seen directors sell out and make the film the producers want as opposed to what they want? Maybe years later they get to release their “Director’s Cut,” but why not just have that be the cut they release to begin with? I’m personally a firm believer that producers don’t make great art. Writers and directors do. However, it doesn’t change the fact that the nightmare of movie jail has always loomed over any director working in Hollywood wanting to stay true to their vision. Especially in wanting to give something a realistic ending. Ironically and impressively, the ending of The Player itself manages to combine the Hollywood ending for some and the realistic ending for others in a way that was meta even before the term “meta” was around.

Let us take a minute to envision the picture of the caricature that Altman and Tolkin painted through the film. The producers of the story seemingly towering over everyone, counting their money and their stars, recycling old ideas. Real life takes ideas from Hollywood like Hollywood takes ideas from real life. Writers and directors trying to crawl their way up only to be continuously knocked down a few steps on the ladder, and everyone else getting stepped over or on by the Hollywood big wigs doing whatever it takes for a box office profit or simply getting their own way, including murder. It’s no secret that people get away with serious crimes every day, especially when they know the right people and have enough money. The fear of being blacklisted in the industry is a bigger fear for most folks than movie jail. Mill is constantly fearing losing his luxurious life Hollywood has gotten him because of his crime. When he hears June talk about criminals, she tells Mill that she thinks that for them, knowing they’ve committed a crime seems like punishment enough. To say that Hollywood does strange things to people would be a major understatement. The modern-day state of Hollywood itself has been less than ideal. More so than it was in 1992. Yet, year after year, we see more and more new voices emerging and breaking new ground in cinema. It’s the big dream for all movie lovers to work in the movies. No one really likes the ugly business side of it, yet we continuously are drawn in by the magic. Perhaps sometime soon, the caricature that Altman and Tolkin crafted for The Player will fade and transform with every new generation that comes into Hollywood and creates a film industry we can all get behind and be proud of. Maybe one day, with the guidance of masters like Altman, we can find our way there.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon

Very well-written article.