| Ryan Sanderson |

Fantasia plays at the Trylon Cinema in glorious 35mm from May 3rd through May 5th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information. These screenings are presented in partnership with the Cult Film Collective.

If you grew up in the eighties or nineties, particularly in the American Midwest, there’s a strong chance you discovered your cinephilia via a VHS rerelease from the Disney vault. The Fantasia fiftieth anniversary edition, for instance, tore across American theaters in 1990 and then trickled through the culture all the way to the little pop-out cupboard under my grandparents’ television. I’m almost certain it was a blind buy, too, because when I suggested to the grandparents in question that we watch the film a couple months ago in anticipation of this piece, the response I got was, “Wait, Fantasia? Really? Why?”

With more investigation I discovered that nobody in that circle of parents, siblings, cousins, and friends really enjoyed the film, despite someone spending twenty 1990 American dollars on a mutilated low-res copy to take up shelf space forever.

That’s the power of Disney.

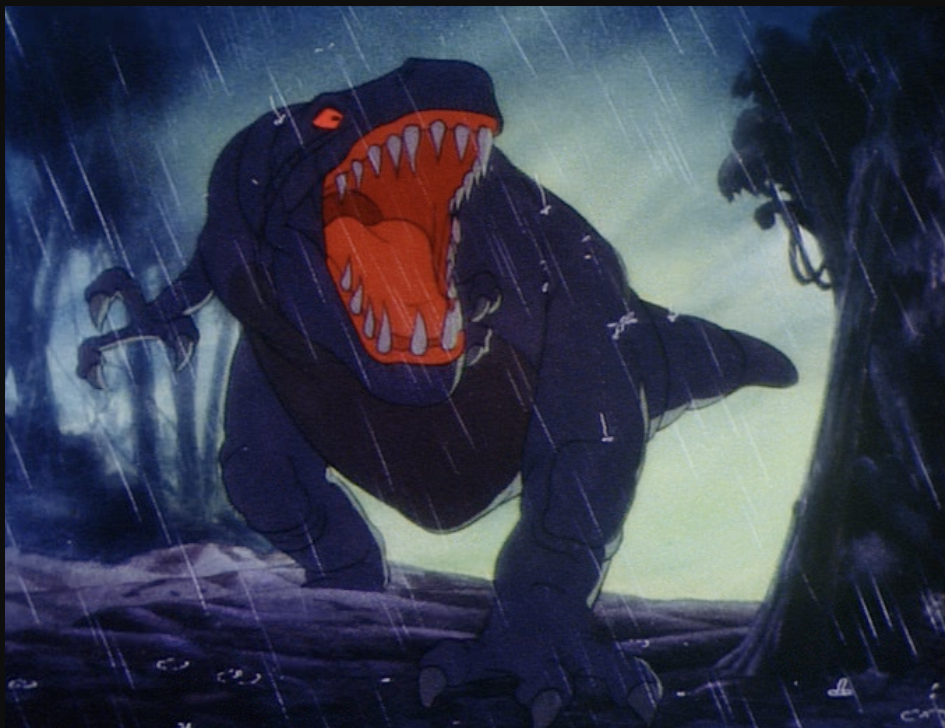

Okay, not nobody. One wide-eyed elder millennial toddler could not get enough of the thing. Dinosaurs, outer space, demons, Mickey Mouse–how could humans create such a thing and then bother to make anything else? The other films I loved had byzantine plots I couldn’t wholly follow, dialogue I half understood at best. I wasn’t looking for their trite morals and easily resolved narrative dilemmas. I wanted cosmic nightmare imagery upon which to project and bolster my own daydreams.

It’s impossible now to recover that person and his viewing experience, lost in the hand-drawn primordial goo of the subconscious, but I’m certain—especially after the recent rewatch—that a bit of that DNA remains in the experience I have at the movies today. I’m still drawn to stories about all the same simple, violent emotions—fear, jealousy, anger, lust; the simplest cinematic language, what Tarkovsky called “shock and catharsis,” what Bowie called “sound and vision.”

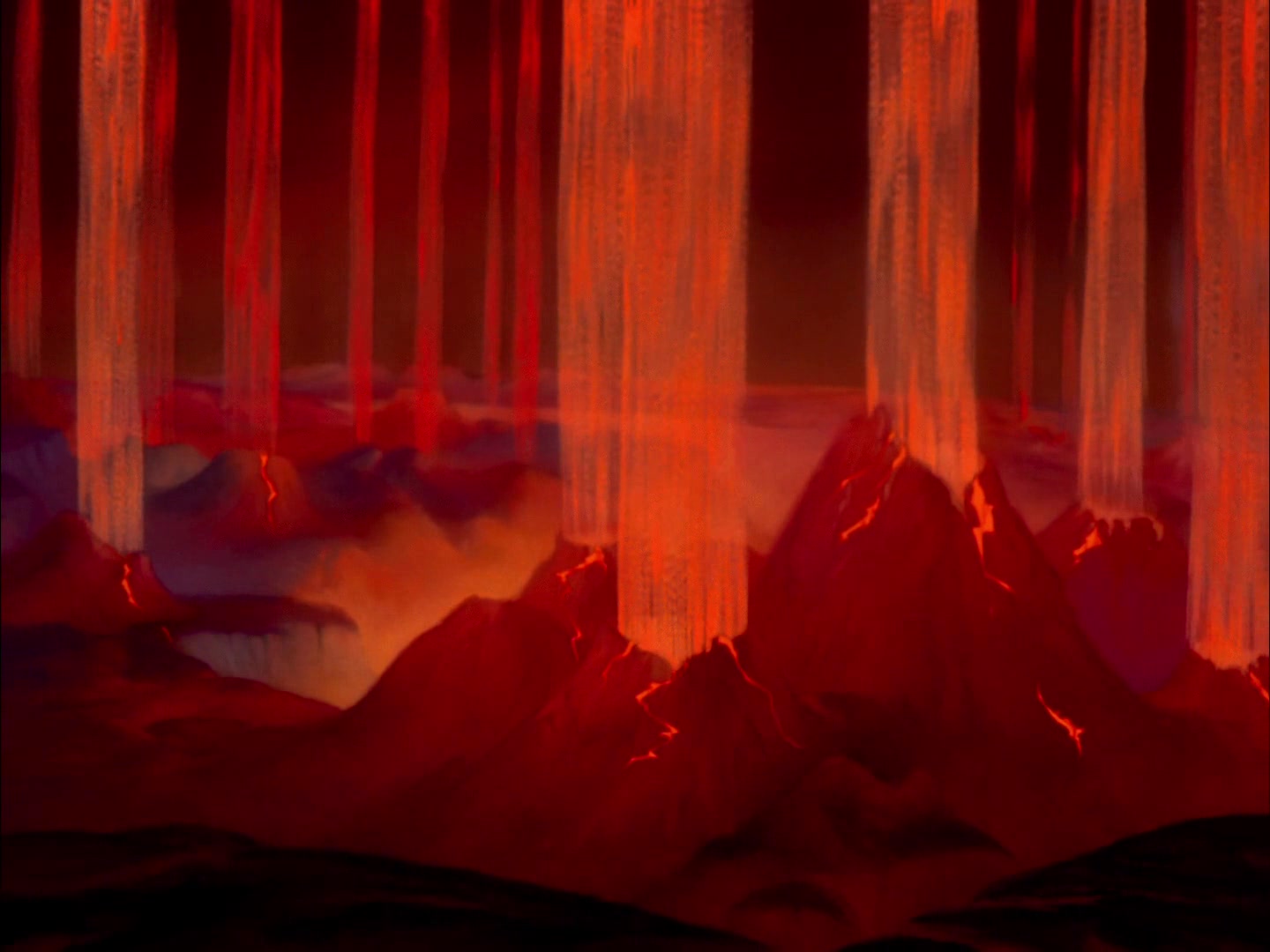

How much of my childhood experience did Walt Disney or his many collaborators intend? I’ll say this: he knew exactly who he was marketing to. He lulled the adults to sleep with instrumental warm-up and classical music theory, then fed their kids a hearty meal of mischief, terror, and death. It’s a film that’s most radical in implication, which is where so many children live and where a great many adults never bother to look. Hey kids, we’re all floating on the cooled crust of a lava ball hurtling through a boundless void. All the creatures that came before us died, many in gruesome and terrifying ways. Let’s bask in the sublime horror and majesty of that while we listen to some Mussorgsky.

Not to mention sex, evolution, and the occult! All were verboten in the circles I grew up in. I nervously conceded the first two points for a while, but I really struggled with the last temptation. My first true obsession was with the macabre, the sublime, the sense of importance and danger of a far-off storm, the mystery of what lies in a dark basement. I prayed (literally, in some cases) to have my nightmares again. The fear of the real world was convoluted, confusing, unaddressable. Controllable fear was a gift.

I was too well-behaved and isolated a boy to go full-on Goth (or anything controversial) but my short stories always ended with someone getting burned to death or buried alive, and at least one Baptist daycare provider was “disturbed” by the monsters I drew in the corner and suggested I needed “counseling.” To my mom’s credit, that woman got told off, and I got moved to the room with the Star Wars minifigure black market hidden behind the bookshelves.

At the same time, the brains of children across the world were being subjected to a new larger experiment, pumped full of universes, mythoi, promotional and commercial appendages for multimedia entertainment brands, toys for animated series spun off of films based on books, each waiting to be filled with interest and personality by eager and undiscerning minds. It was quaint compared to today’s climate, but it was also an invasive species in an environment wholly unprepared to accommodate it.

And, of course, not the kids’ fault! They were just doing what kids do—in my mind perhaps the most endearing thing about humanity as a species—meeting new stimuli like a friend, growing and molding in response to the universe, prepared to wake up and adapt to any kind of wild possibility that might greet their newborn vision. And what a world! Neon daydreams in all directions, the mundane, everyday monotony of the workaday, labor-for-industry life of their ancestors a mere dull interruption to a mental life of whimsy and adventure, hopefully never to learn the unforgiving totality of the lessons hidden inside the fairy tales. For example, the meaning of “too good to be true.”

My feelings today about all that narrative turbocharging of life are complicated. I can’t help but be grateful for the various avenues provided by fantasy and film to deal with my emotions in a culture that emphasized grit and virtue over any sort of self-knowledge. Time and again I went to the movies and felt fully the complex terror of being alive; a portal to a world I could mold ever so slightly to my own rules and needs.

At the same time, I don’t think any of us can look back on the films we loved as kids (especially not the Disney films) without cringing, not just at the antiquated and clearly destructive ideas they communicated, but also at what we went on to do with those ideas. Fantasia in particular is a product of 1940s Disney and there’s some jaw-dropping racism and other regressive ideologies scattered throughout its imagery. I didn’t clock the exact implications at the time, but my mind certainly normalized those images.

It’s a mixed bag. Everything in this world is. “Cursed dreams,” as Hayao Miyazaki once said. Fantasia, for example, presents a stunning vision of what it means to be alive, a vision just dawning on larger humanity in 1940, still suppressed and controversial in many circles when I got my hands on it half a century later—a cold, expansive universe explodes into violent energy and light, plasmic energy balls cooling, molecules reforming into organisms, organisms evolving and complexifying, monstrous empires rising violently and then starving at the whims of a world that neither sees nor respects them. But story, mythology, personality, projected onto those same events gives them new life; a more forgiving, friendly nature. And what cannot be forgiven or shrugged off, like death, insecurity—well, given enough time, we’ve figured out how to contain that in stories as well. All in a two-hour production narrated by the outlines of boring old white men holding bulbous wood statues talking about musical history.

It’s far from the first film I would show a kid today. But it served a purpose, an escape I couldn’t help but eagerly accept, with results I clearly liked so much I repeated them over and over again the next thirty years of my life.

So thank you, Walt Disney, for your weird, abstract, terrifying, horny, sometimes boring, sometimes cruel, sometimes awe-inspiring snuff film aimed at children. Sometimes I wonder if this one had been more successful, maybe I’d be happier with the media climate your brand has come to dominate.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon