| Dylan Hawthorn |

Strangers on a Train plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, April 7th, through Tuesday, April 9th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Major spoilers for Strangers on a Train and minor spoilers for Rope ahead

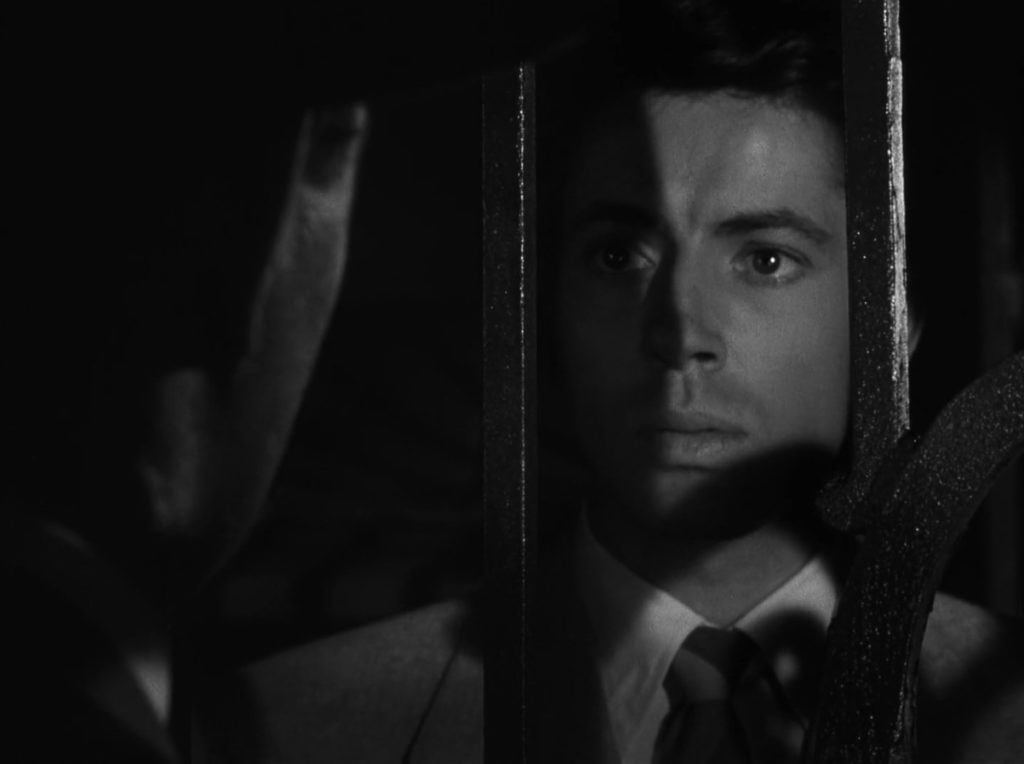

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), Guy Haines (Farley Granger) is a man who seems to have it all. He’s marrying a senator’s daughter, his tennis career is taking off, and he’s the picture of masculinity in classic suits. On paper he is the opposite of the film’s antagonist, Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker). Bruno is single, spoiled by his mother, and his necktie is gaudy. As the film plays out, their fates grow intertwined, we realize that the two may be more alike than we expect.

Before we actually start the movie, though, we see the Warner Bros. logo, followed by a screen announcing the lead actors:

Farley Granger

Mr. Granger appears by arrangement with Samuel Goldwyn

Ruth Roman

Robert Walker

The fine print sticks out in an otherwise unremarkable list of names. Why do we need to announce this? Why does Samuel Goldwyn need to arrange for “Mr. Granger” to appear in a movie?

Before we answer that question, let’s spend some time talking about the ever-underrated Farley Granger. As an actor whose career spanned many mediums and decades, he witnessed tremendous changes to the film industry. Exploring his life gives us insight into the difficulties of being an actor within the Hollywood star system, particularly an LGBTQ+ actor, and highlights the challenges of breaking out of this system.

So, Who Is Farley Granger?

Born in 1925, Granger spent his early years in San Jose, CA, and caught the acting bug early. After proudly performing not just his own part but that of an absent classmate in a Christmas play, he said he “knew as a certainty that it was [his] destiny to be an actor.”1 His big break, however, came at 17, just shy of high school graduation. Granger’s father was a clerk at the Hollywood unemployment office and became chums with Harold Lloyd, the silent comedian known for dangling from a clock face in Safety Last! (1923) who regularly came in for his unemployment check. Some may have balked at asking for career advice from an unemployed actor, but not Granger’s father! Instead, Lloyd provided information about an amateur theater in Hollywood that talent agents frequented. In Granger’s first and only play with the company, a talent agent and casting director looking for a clean-cut, typical teenager spotted him.2

Entering the Studio System

After a call from the agent, Granger and his parents drove to Samuel Goldwyn Productions the next day and left with a contract. Granger would spend the next seven years with the studio, not including time spent in the armed forces (Granger was planning on enlisting and serving in World War II upon turning 18). He would be paid $100 a week, which is about $1793 a week after adjusting for inflation.3 Granger later described Goldwyn as “tightfisted,”4 “tyrannical,”5 and “homophobic,”6 a micromanager of his career and personal life. Goldwyn may have had a particular temper, but this dynamic wasn’t unusual.

Steady work and professional resources were excellent benefits to signing a studio contract. However, contract players also entered a system dedicated to shaping actors in a way that suited the studio. Publicity departments decided what sort of image a player would personify, such as the glamorous leading actor, the femme fatale, or the sidekick. Press tours, fan magazines, and planted items in gossip columns aided this effort. Granger, for instance, was introduced as “a typical American boy, whose proudest possession is the electric shaver which he began using on his 17th birthday” in an infantilizing press release for his first film, The North Star.7

Actors under contract were also expected to perform whatever roles were handed to them whether they liked them or not. Their studios could loan them to other production companies, but the roles might not have fit them and their salaries would remain the same. Turning down roles resulted in suspension without pay and an extension of their contract. In the words of UCLA professor emeritus of film history Howard Suber, “These contracts gave all of the advantages to the studio and made it nearly impossible for stars to have a say in their careers.”8

Studios had great power to boost careers, but that power could easily force them out of the industry if actors rebelled against the machine’s expectations. Granger was initially lucky. After positive experiences working on two WWII propaganda films (The North Star and The Purple Heart), he served four years in the US Navy and made the noir film They Live By Night in 1948. It was this role that caught the eye of Alfred Hitchcock as he sought to cast Rope.9

Hitchcock and Actors

Hitchcock is rumored to have said that actors are cattle. In a later interview, Hitchcock clarified that he didn’t mean that literally, but that actors should be treated like cattle. “They have to become secondary to the whole,” he added.10

The quote may be blunt, but one that makes sense when considering Hitchcock’s working style. With his writers and production crew, he invested much of his energy in pre-production with detailed scripts and storyboards. Obsessed with this vision, he once said that the fun of making a film was over once the script was finished.11

For a director who was relatively uninterested in “directing” actors but deeply concerned with visual style, the Hollywood star system turned out to be a boon. Using the pre-existing system and audience expectations, Hitchcock could increase suspense by casting a famous star in a role that went against their type. As he said when announcing his decision to move to the United States: “I’m itching to get my hands on some of those American stars. . . Some of them are so efficient that it’ll be a pleasure to direct them; and there are others I should very much like to debunk.”12

This “debunking” is very clear in the casting of Granger’s castmates in Rope and Strangers on a Train. At the time, Jimmy Stewart’s morally suspect professor was an unusual role for him. Robert Walker, took a long string of “boy next door” roles before taking on the charismatic villain he is so praised for portraying.13 While not as drastic a change, Granger’s casting in both films bent his existing “type.” Rope sees him graduate from the “all-American boy” to an anxious murderer. In Strangers on a Train, his thoughtful performance makes you believe for a second that his character is desperate enough to go through with Bruno’s murder swap.

The Gay Icon

Rope and Strangers on a Train are also noted as two clear examples of queer subtext present in Hitchcock’s filmography. Granger’s roles support this thought. In Rope he plays a plaintive, yearning young man eager for approval from his lover and his professor. Strangers on a Train benefits from his portrayal of ambiguity—is he repulsed by Bruno, or does he long to be like him? His openness to leaning into the homo/bisexuality of his characters could draw from his lived experience.

Granger’s desire for freedom extended beyond his professional life. He was also open about not being heterosexual.14 In an oft-quoted section of his autobiography, he wrote, “I have loved men. I have loved women. I will talk with affection and without guilt or remorse about both in this book.”15 And boy did he love both men and women! In a book chapter I desperately hope is true and not a tall tale, he described the night he “lost his virginity twice” while serving in the Navy, first having sex with a local Hawaiian woman and then a fellow sailor hours later. In the pages that follow, he name-drops many fellow stars he had relationships or brief flings with over the years, such as Shelley Winters, Jean Marais, Ava Gardner, and Leonard Bernstein.16

Relevantly, one of those people was Arthur Laurents, the screenwriter of Rope. They met during the filming of the movie and had a messy affair. Laurents and Granger both confirm they openly discussed the romantic relationship between Philip and Brandon behind closed doors, which surely informed Granger’s portrayal of Philip.17

It was definitely pragmatic for Granger not to publicly come out given the realities of the Hollywood blacklist at the time and his own masculine leading man image to protect. He also seemed indifferent to the idea of being “out” or identifying himself with his sexuality. As he wrote:

I never have felt the need to belong to any exclusive, self-defining, or special group. … I had no desire to become involved with any of [the cliques of gay actors]. I was never ashamed, and I never felt the need to explain or apologize for my relationships to anyone.18

Granger was unapologetic about who he was in a time when that could carry deep consequences. This tenacity served him well in his journey to do what he truly loved and to take on a studio contract system he felt was unfair and damaging to his career.

So, Who Is Farley Granger? (Redux)

Granger attracted contemporary popularity in the 1930s-50s thanks to his steady work in his contracted movies and studio-flamed media coverage of his relationship with Shelley Winters. However, the forced publicity drained him, and he longed to recapture that childhood rush of connecting with an audience on stage. In 1953, after ten years, sixteen films, and several periods on contract suspension for refusing to accept uninspiring roles, he emptied his bank account to buy out the remaining two years of his contract.

For the next 33 years, he continued to amass credits in film, TV, and theater. Notably, he starred in Visconti’s film Senso (1954) and appreciated Visconti’s methodical direction and Italy’s gorgeous studios, as opposed to the churn of the Hollywood studio system and studios where “nothing was real except anxiety, insecurity, and fear.”19 Other highlights included starring in the first revival of The King and I and a performance in The Crucible that drew Arthur Miller backstage to congratulate him. He was less proud of a string of Italian Giallo films he worked on during the early 1970s while living in Rome. Personally, I wish I could have seen his turn as Mr. Darcy in a musical adaptation of Pride and Prejudice in 1959 (the show closed after two and a half months on Broadway, to negative reviews).20 Along the way, he met his partner, theater and television producer Robert Calhoun, on a theater tour in 1963. They remained partners for the rest of their lives.21

As for Strangers on a Train, I believe Granger’s performance is oft-overlooked. Reviews for the film tend to focus on Walker’s role. This is for good reason; Bruno is a captivating character while Guy is mostly a by-the-book leading man. However, Granger’s was the one I gravitated toward when I first saw the film. Sure, this was initially less because of his acting chops and more because of his status as the dreamiest leading man in the Hitchcock canon (source: my eyes). But he is more than a pretty face. The existing all-American masculine persona he brought to the role of Guy provides a solid foundation for the movie’s ensuing mayhem and establishes audience expectations. At key points, he allows the audience to see the character’s fascination and fear of Bruno, suggesting the characters’ subtle similarities and cracking the facade of the leading man.

Granger may have resented being typecast into roles he found boring. But Strangers on a Train complicates that typecast in a way that echoes his other rebellions against the Hollywood system. He considered shooting the film to be one of his happiest filmmaking experiences,22 and I think this opportunity to subvert the leading man is a large reason why.

His Legacy (In His Own Words)

Image Source: Rich, Frank. “Theater: Wilson’s ‘Talley and Son.’” The New York Times, October 23, 1985, sec. C19. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1985/10/23/098708.html?pageNumber=71.

As I was reading books and watching movies and hunting down interviews to research Granger’s life, I noticed how few “hit” movies he had in his lengthy filmography. Initially, I judged him as less “successful” than other Hitchcock leading men such as Cary Grant. This, of course, defines success narrowly and he would disagree with this assessment. His autobiography ends with the night he won an Obie (prestigious off-Broadway honors) in 1986 for his performance in Talley and Son. He concludes:

I had realized my ambition to become a real actor, and had been lucky enough to do some extremely good things in each of the three golden ages I worked my way through: movies, live television, and theater. The Obie Award was much more to me than an affirmation of work well done, it was proof that the world [of theater] was where I belonged.23

The average person may not know Farley Granger today. However, he was clearly fulfilled and happy with his accomplishments and his inner compass. This was despite studio and social pressures disincentivizing this success. In addition to a vibrant career and a long resume, he was able to say no to being a cog in the studio machine. I admire him for that, and knowing his story makes watching his movies that much more of a delight.

Footnotes

1 Farley Granger, Include Me Out, “Childhood Memories.”

2 Granger, Include Me Out, “Discovered.”

3 Granger, Include Me Out, “Indentured.”

4 Granger, Include Me Out, “Millie.”

5 “Farley Granger – A Rebel Actor of the Studio System,” Turner Classic Movies, May 28, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NsovrbrOQSk&t=2151s.

6 “Farley Granger: Goldenboy,” The Advocate, November 17, 2015, https://www.advocate.com/arts-entertainment/film/2011/03/29/farley-granger-hollywood-goldenboy.

7 Lesley L. Coffin, Hitchcock’s Stars, “Rope.”

8 Brent Lang, “How Olivia de Havilland Took on the Studio System and Won,” Variety, July 27, 2020, https://variety.com/2020/film/news/olivia-de-havilland-lawsuit-gone-with-the-wind-warner-bros-1234717146/.

9 Coffin, Hitchcock’s Stars, “Rope;” “Farley Granger – A Rebel Actor of the Studio System.”

10 Coffin, Hitchcock’s Stars, “Introduction: Hitchcock’s Livestock.”

11 Roger Ebert, “Hitchcock: “Never mess about with a dead body—you may be one…” RogerEbert.com, December 14, 1969, https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/hitchcock-never-mess-about-with-a-dead-body-you-may-be-one.

12 Coffin, Hitchcock’s Stars, “Introduction: Hitchcock’s Livestock.”

13 Coffin, Hitchcock’s Stars, “Strangers on a Train.”

14 In a 2007 interview with The Advocate, Granger doesn’t comment on whether he identifies as gay or bisexual. “I’m too old to worry about that. I’ve done too much.” Therefore, I will not speculate on his specific orientation in this piece.

15 Granger, Include Me Out, “Sex, Sex, Sex, Sex….”

16 Granger, Include Me Out; “Affairs to remember,” The Advocate, November 17, 2015, https://www.advocate.com/politics/commentary/2007/03/12/affairs-remember.

17 Granger, Include Me Out, “Rope;” Coffin, Hitchcock’s Stars, “Rope;” Vito Russo, The Celluloid Closet, 92

18 Granger, Include Me Out, “Sex, Sex, Sex, Sex…”

19 Granger, Include Me Out, “The Shiner;” Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction, 338.

20 Granger, Include Me Out, “On Broadway.”

21 Granger, Include Me Out, “Four Parts in Three Plays in Two Cities.”

22 Granger, Include Me Out, “Hitchcock Number II.”

23 Granger, Include Me Out, “The Obie.”

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon