| Matthew Christensen |

Shadow of a Doubt plays at the Heights Theater on Thursday, April 11th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

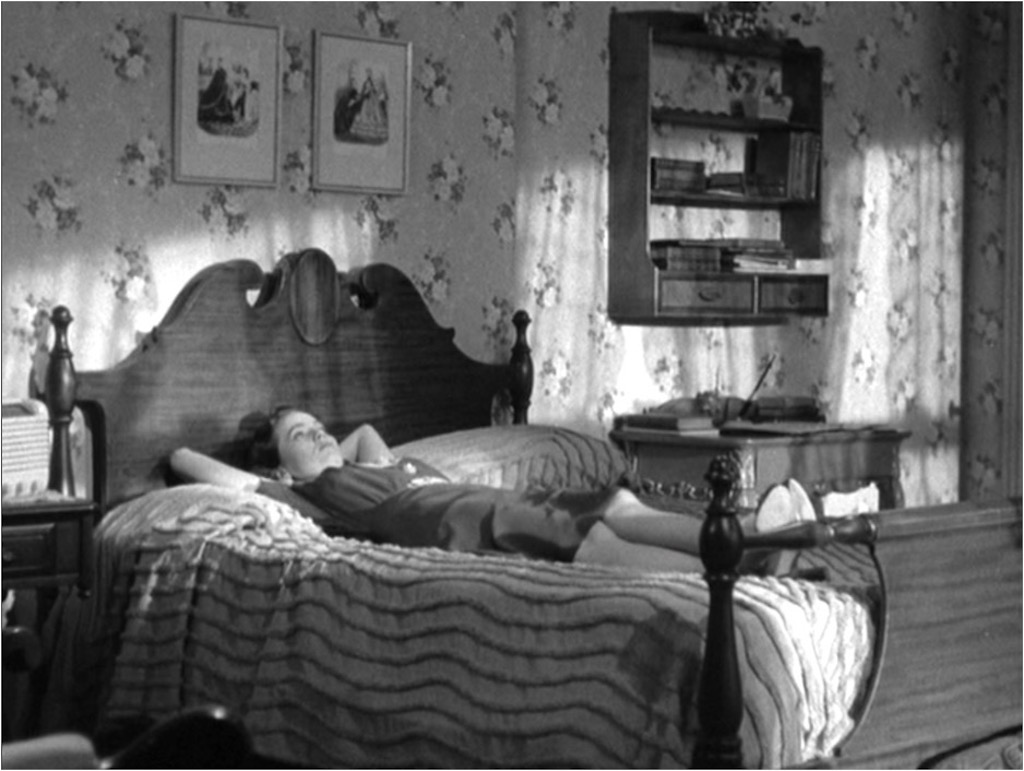

A lot of what’s been written about Alfred Hitchock’s Shadow of a Doubt has to do with the use of doubles. As with Strangers on a Train (1951), these dichotomies invite us to look at the muddied line between good and evil, and in doing so expose “what lurks underneath the surface”.1 The relentless application of doubles—two similar introductions of two characters named Charlie reclining on their beds, two detectives trailing Uncle Charlie in two cities, two crime buffs devising ways to kill one another, two dinner table sequences, a bar called the ‘Til-Two (where Uncle Charlie orders two double brandies) and a waitress has worked there for two weeks, two attempts on Charlie’s life before a final confrontation—serves as a kind of structural commentary reinforcing the film’s focus on innocence and experience and the harsh lessons that come with it.2

The moral core of Shadow of a Doubt is Charlie Newton, played with a compelling blend of wholesomeness and cynicism by Teresa Wright. Charlie is an anomaly when placed next to typical heroines of Hitchcock, or even noir, films. She is neither a cool blonde with the sexual sophistication of Grace Kelly. Nor is she a femme fatale manipulating hapless victims. Instead, she is an all-American girl whose innate goodness we understand not as naivety but as a moral force challenged by the corrosive presence of her murderous Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotton), a serial killer known as the Merry Widow Murderer. Inextricably entwined, Charlie and Uncle Charlie share more than a name. In a moment soon after he has arrived to stay with the Newtons, Uncle Charlie takes his namesake aside and presents her with a gift. As the camera presses in for a more intimate framing of the pair, Uncle Charlie places an emerald ring on Charlie’s finger. The pseudo-engagement is underscored by an off-key rendition of Mendelssohn’s “Wedding March”.

Hitchcock shows us this is no typical uncle-and-niece relationship. Charlie even acknowledges, “We’re not just an uncle and a niece. It’s something else”. In spite of Charlie’s later statement that they are like twins, Hitchcock’s camera shows us a more intimate relationship constantly framing the two romantically. When walking in downtown Santa Rosa, Charlie clutches her uncle’s arm, enjoying the fact that her girlfriends wonder if he is a new beau. Hitchcock further reinforces this incestuous imagery through contrast. When detectives Jack Graham (Macdonald Carey) and Fred Saunders (Wallace Ford) come to the Newton home, posing as pollsters, Jack becomes enamored with the young woman. However, the visible restraint and lack of chemistry between Charlie and her would-be lover appears stagy and wooden when compared to scenes between the Charlies.

The connection Hitchcock establishes does more than simply link the two. It shows us moral ambiguity: despite his corrupt nature, Uncle Charlie desires a return to nostalgic innocence in reuniting with his sister, Charlie’s mother. Young Charlie, on the other hand, develops an awareness of the darkness in the world as well as the realization that she is capable of murder. In an early scene, Charlie expresses boredom with her idyllic experience and wires her uncle, believing him to be just the person to shake things up. But soon after her uncle’s arrival, she senses all is not right. Hitchcock shows this through her sudden realization that Graham is a detective trailing her uncle. Charlie’s revelation constitutes more than a psychic connection with her uncle, who also sees through Graham. It demonstrates Charlie’s innate perceptiveness. Unlike her sister Anne, who instinctively mistrusts her uncle but cannot articulate why, or her mother who, after Charlie’s two brushes with death, cannot put two and two together, Charlie possesses a talent for recognizing evil in the world, a talent that emanates from her connection with her uncle.

During dinner one night, Uncle Charlie breaks the fourth wall in a disturbing speech expressing what amounts to his justification for the killing of rich widows, a film moment as cynical and shocking as those we will see 30 years later in Frenzy (1972). The scene begins with an establishing shot of the family, then cuts between Charlie, Charles, and Mrs. Newton. As the conversation turns to women in small towns versus cities, we move from a medium close-up of Charlie to a shot of Uncle Charlie from her point of view. The prolonged, tense close-up of Uncle Charlie as he delivers his cold philosophy in trance-like tones is broken when Charlie cries, “But they’re alive! They’re human beings!” Her protestations read like questions, as if Charlie recognizes the truth in her uncle’s statements: that people often are motivated by greed, and are prone to vile, self-serving behaviors. Her look of resignation confirms her begrudging acknowledgment of the truth of his worldview.

Charlie dashes from the dinner table only to be pursued by Uncle Charlie, who drags her into the ‘Til-Two, a bar that reminds us that even picture-perfect towns like Santa Rosa have a seedy side. Here we are introduced to a character whose minimal screen time belies her importance to the film’s moral narrative. Former classmate and waitress at the bar, Louise Finch (Janet Shaw) is the antithesis of Charlie: after losing her drug store job, Louise has struggled to hold down a job—“I’ve been in half the restaurants in town,” she laments. She now works at the ‘Til-Two, an establishment Charlie blanches at entering. Even Louise acknowledges this is not a place frequented by well-raised girls; she is surprised to see Charlie. One cannot help but see the gulf that separates these women. Louise is a young woman whose experience of life has tarnished her, beaten her down in some profound way. She presents a cynical possibility for Charlie’s future, innocence tarnished by the depraved world Uncle Charlie inhabits, or by Uncle Charlie himself. Quickly recognizing the implications of maintaining a bond with her uncle, Charlie returns the emerald ring which she has discovered is a souvenir from a murder. It is akin to a romantic breakup. Charlie’s symbolic uncoupling, paired with the news that the police in the East mistakenly believe they have found and killed the Merry Widow Murderer, results not in her being free of her uncle, but being bound even more closely to him in having to keep his secret. But it is now Uncle Charlie who needs to be rid of the association, knowing he can’t truly be safe as long as his niece is alive.

This point marks a development in Charlie’s moral self-awareness. Her uncle makes several attempts on her life, and with each one Charlie responds with intensifying venom. She first threatens to kill her uncle if he doesn’t leave. Next, when he “rescues” her from carbon monoxide poisoning, Charlie regains consciousness with just enough energy to coldly whisper, “Go away. Go away.” Moments later Charlie retrieves the incriminating emerald ring with its engraving, showing her fierce protection of her family’s peace and a rejection of her uncle. The man she ushered in to “shake up” the family must now be removed.

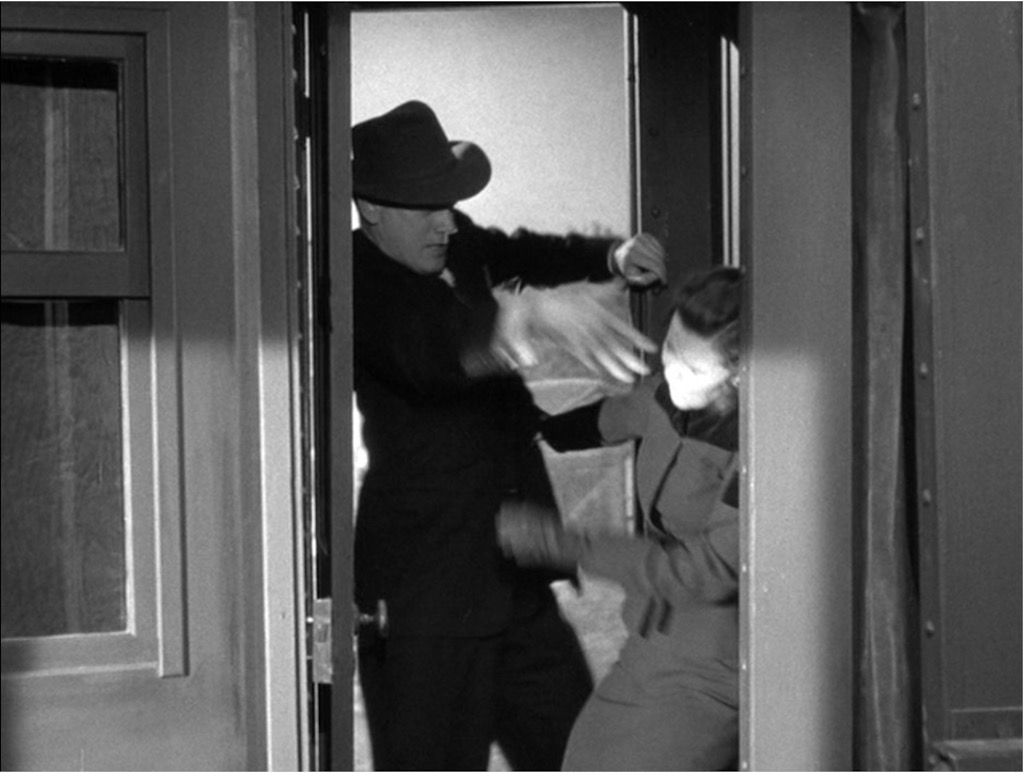

The final confrontation comes when Charlie (dressed in a black suit) boards the train to see her uncle off. In a last attempt to be free of her, Uncle Charlie tries to throw her from the moving train. He holds her near the door instructing her, “Not yet, Charlie! Let it get a little faster, just a little faster. Now!” It is at this point that Charlie pushes herself away, and in doing so, shoves Uncle Charlie onto the tracks of an oncoming train. The choice of Charlie’s black costume can be read as funereal, foreshadowing Uncle Charlie’s death, or it may signify Charlie’s own potential for evil.

The film abruptly ends outside of the church at Uncle Charlie’s funeral. The scene, cynically underscored by a sermon lauding Charles Oakley as “brave, generous, kindly,” demonstrates how people would rather turn a blind eye to evil than acknowledge it on their doorstep. Graham’s statement that the world is not that bad, but “sometimes it needs a lot of watching. It seems to go crazy every now and then,” is a wartime call for vigilance on the home front. Many read Graham’s reappearance here as an assumption that the pair will marry and the sadder-but-wiser Charlie will retreat to the same dull domestic existence as her mother. But the fact that the couple are on the steps of the church and not in it signals ambiguity on this point. The two seem bound more by moral responsibility than love; they serve as gatekeepers, protecting domestic tranquility by hiding messy truths.

This pessimistic depiction of homegrown malignancy and the attempt to preserve a facade is just as relevant today as it was in the 1940s making Shadow of a Doubt a timeless noir classic.

Resources

1 Eggert, Brian. 2013. “Shadow of a Doubt (1943) – Deep Focus Review – Movie Reviews, Critical Essays, and Film Analysis.” Deep Focus Review. https://www.deepfocusreview.com/definitives/shadow-of-a-doubt/.

2 Spoto, Donald. The art of Alfred Hitchcock: fifty years of his motion pictures (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1992), 120.

Edited by Finn Odum