|Hannah Baxter|

The Plot Against Harry plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, March 22nd, through Sunday, March 24th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

How does a movie end up in front of theater audiences? Best case scenario: it’s the product of a major studio, with big stars, a respected director, and/or superheroes. The studio will likely handle distribution and marketing; if not, distributors will pay handsomely for the right to shepherd such a film into theaters. What follows are the stories of movies that, lacking these advantages, took unconventional paths to theatrical distribution. Plus, we’ll look at one feature that’s still fighting its way to an audience whose dearest wish is simply to see it.

In 1969, director Michael Roemer had high hopes for his new movie, The Plot Against Harry. A German Jew who fled to England on the Kindertransport in 1939, Roemer arrived in the United States in 1945 at age 17. After college he worked as a production manager, film editor, and assistant director before directing his first film, Nothing But a Man (1964). In 1966, on the strength of that debut, Stimson Bullitt, the president of King Screen Productions (a short-lived production company with its own complex history), approached Roemer. Bullitt offered to finance Roemer’s next project, telling him to do whatever he wanted. Roemer came up with The Plot Against Harry, the comic redemption story of Harry Plotnick, a small-time Jewish gangster.

Roemer and Bullitt held preview screenings for friends, potential distributors, and other industry professionals, but The Plot against Harry didn’t click with viewers. Here’s Roemer on why that was:

Harry’s out of joint with things. We understand how they hang together, but he doesn’t, and that experience is now familiar for audiences, but I don’t think it was then. People told me when they came out of the few screenings we had that they didn’t know what was going on, and if you don’t know what’s going on, I don’t think you can laugh.

Distributors took a pass. King Screen Productions gave up on the movie, and after a few more years and a few more failed pitches to investors, so did Roemer. He went on to make documentaries and TV movies for PBS while teaching film as an adjunct at Yale. In the late 1980s, he decided to have his early films transferred to video to show his children (one of his daughters, Ruth, appears in The Plot Against Harry.) He perked up when he heard the video transfer technician laughing.

That’s when Roemer took a leap of faith, investing what must have been a significant sum in two 35-millimeter prints of the film, which he shipped off to the New York Film Festival. It was screened there and at the Toronto Film Festival in 1989; the following year it was screened at Cannes. Success bred success: U.S. and European distributors bought the rights to the film, twenty years after it was made. Critics hailed it as a long-buried gem. And finally, Roemer’s children could watch it, not at home on videocassette, but in theaters, where it belonged.

These days, it’s become hard once again to track Harry Plotnick down. You won’t find it on the Criterion Channel, Netflix, YouTube, or Tubi. If you want the 2005 DVD edition, it’ll cost you $65 on eBay. By far the best—and cheapest—option is to see it in its new restoration at the Trylon. Like Harry Houdini wrestling free from a straitjacket at the bottom of a river, Harry Plotnick rises again.

The Little Movie that Could

In 1971, a young, green Steven Spielberg persuaded executives to let him direct an ABC Movie of the Week based on a story by Richard Matheson. Duel’s journey to theaters, while also unusual, contrasts with Harry’s. For one thing, Harry took more than two years to finish; Spielberg had to shoot his movie in less than two weeks, with cast and crew “literally running” from set to set.

Spielberg recruited Movie of the Week alum Dennis Weaver to star as David Mann, who’s navigating California back roads in his tomato-red Plymouth Valiant when he incurs the wrath of a tanker truck driver. The 47-year-old Weaver showed up to the rushed shoot with his “game face on,” Spielberg said, even performing risky stunts.

Duel aired days after it wrapped to phenomenal Nielsen ratings: a third of U.S. households with televisions tuned in. It aired once more before Universal Pictures decided to distribute it to theaters. The problem was, it was only 74 minutes long. To qualify as a feature film in Europe, it needed to be 90 minutes, so Spielberg and Matheson added a few more scenes.

As his name implies, Weaver’s character is an everyman. He never becomes an action hero, never goes berserk like a late-career Liam Neeson. Much of the extra material emphasizes his passivity, as when Mann calls his wife to apologize for not stepping in when their friend sexually harassed her. In the film’s extended opener, Mann listens to a radio sketch wherein a man calls the Census Bureau for advice on filling in his form. The caller, a stay-at-home dad, is embarrassed that he isn’t “the head of the household.” These moments appear to suggest what a “real man” is like, perhaps insinuating that Mann isn’t one. For the final moments of Duel, Spielberg even had Weaver channel his quirky hotel clerk from Touch of Evil:

“Can you give me a manic dance when the truck dies? Can you bring that character back to life? How would he react if he had been chased by this truck for an hour and a half?” Dennis said, “Say no more. I know exactly what you’re getting at.”

Weaver gives us the least macho moment of triumph you can imagine, beautifully complimenting the film’s less-is-more resolution.

The Classic that Outgrew its Cult

You might wonder at distributors who passed over The Plot Against Harry, but it’s plain to see why Tommy Wiseau, who wrote, directed, produced, and starred in The Room (2003), had to distribute it himself, too. Wiseau also promoted it, renting a billboard in L.A. that stayed up for years, costing him thousands a month.

I first saw The Room a decade ago in a college-town midnight screening. I stared at the poster outside the theater with its black-and-white close-up of Wiseau, eyes unfocused, perhaps looking inward at his own inscrutable thoughts. I knew nothing about the movie, except that I should probably get tickets.

Naturally, I loved it. There is pure joy in watching something this inept, especially in the company of an appreciative audience. Merely “good” movies don’t offer this experience. Most bad movies need MST3K-style riffing to get you there. It’s only the very worst that can take you to such heights of disbelief and elation. The Room is special, and that’s why, after its initial, abysmal run in a few L.A. cinemas, it enjoys widespread screenings 20 years later. Plenty of Hollywood types are big fans. The writer and actor Joe Lo Truglio told Entertainment Weekly, “when we do a take, and it seems bad, a comment about The Room is often made. ‘Dude, your heart was in the right place, but the acting wasn’t. You Roomed it!’”

The Room got access to an even bigger audience with the release of The Disaster Artist, a James Franco project that I paid good money to see. This movie, based on a Room actor’s memoir, has no real reason to exist. The best part is the end credits recreating classic scenes from The Room and showing the original in split screen. Recently, I was slightly disheartened to read about what is said to be a scene-by-scene remake of The Room. Proceeds will reportedly go to AIDS research, so it would be ridiculous to say they shouldn’t make it. Yet I can’t help but wonder if they considered any other “best bad movies.” Plan 9 from Outer Space, anyone?

The “Perfect Object”

Here’s Harry Shearer on a Room-esque experience:

[S]eeing this film was really awe-inspiring, in that you are rarely in the presence of a perfect object. This was a perfect object. This movie is so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is.

He was talking about The Day the Clown Cried, which maybe, just maybe, is coming soon to a theater near you. Filmed in 1972 and set in WWII-era Germany, the film is apparently so bad that only a tiny few have seen the rough cut.

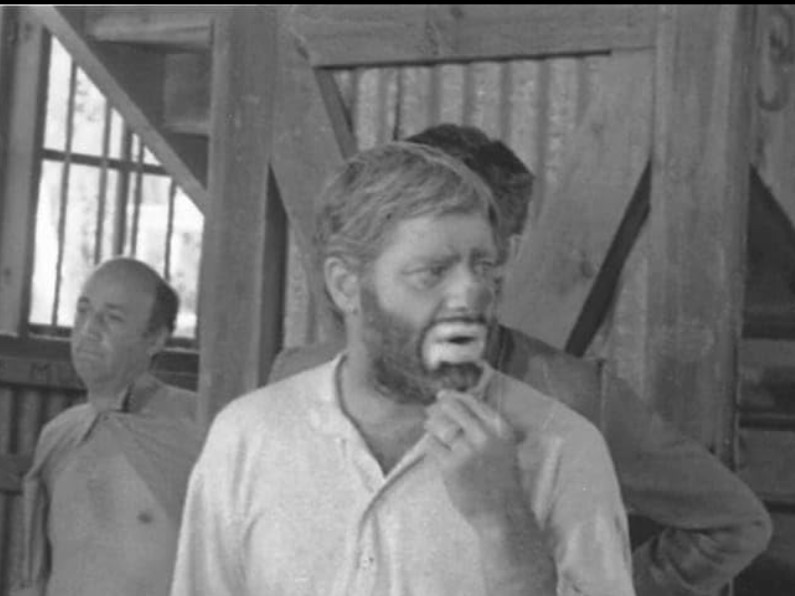

Jerry Lewis, who also directed, plays Helmut Doork, a bad clown. I know, I know—that’s tautological. But Doork is so unfunny he gets fired by the circus and beat up by a gang of prisoners, then angers the Nazis and ends up in a concentration camp, where he dies alongside his final audience.

Like Wiseau, Lewis funded the production himself—in part by selling off family properties. Lawsuits and Lewis’ eventual change of heart kept the film under wraps. But before his death, Lewis arranged for the Library of Congress to receive what may be a copy of the rough cut—with a stipulation that it not be shown until June 2024.

Is there any chance this film will show up at the Trylon in a restored print? Certainly, there’s a built-in cult audience, what with dramatic readings of the screenplay and heated speculation on Reddit among connoisseurs of poor taste. To be fair, there’s at least one critic (admittedly, he’s French) who has seen the rough cut, and who thinks it may actually be a good film.

In the mid-1960s, before Harry Plotnick was so much as a twinkle in Michael Roemer’s eye, Roemer considered making a movie based on Elie Wiesel’s Dawn. However, he concluded that “there was no way” to make “any…fiction film about the Holocaust.” Lewis, who of course was also Jewish, came to the opposite conclusion–that “the picture must be seen.” His heart was in the right place, but he Roomed it.

Edited by Finn Odum