|Nazeeh Alghazawneh|

Nothing but a Man plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, March 22nd, through Sunday, March 24th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

The idea of someone “being ahead of their time,” whether it be an artist, an author, an activist etc., is kind of paradoxical. The phrase implies that broad social, philosophical or political landscapes will change inevitably, develop autonomously, independently of the population within them. It’s a phrase that can only be used after the fact, as if, of course things were always going to turn out this way, ignoring the quantum mechanics of infinite alternate timelines for human civilization. The phrase rings most hollowly, most flippantly, within the context of the conditions experienced by oppressed, marginalized groups in their determination for civil rights, for human dignity. There’s an inclination, rooted in the comfort of easily digesting our reality, to view time as an objective, finite chronology that’s only going in one direction. On a scientific basis, for something alive like a tree, sure, but for us, because our brains are so “advanced,” that’s not the case. Of course our bodies age as they age but it’s our minds that render virtually everything relative.

Perhaps inadvertently adhering to “form follows function,” Michael Roemer’s 1964 feature, Nothing But a Man, was a film that remained largely invisible upon its release, featuring social concerns and themes that were not widely appreciated at the time. The starkly told, somberly directed neo-realist tale of Duff Anderson, a Black transient war veteran performing arduous railroad labor in the American South, near Birmingham. As Duff traverses the extremely radical goal of starting a Black family on his own terms—with dignity—the film’s tone feels muted, hushed, holding its breath, balancing an atmosphere that walks on eggshells. The characters speak flatly, without inflection, sparse dialogue constantly carrying double meaning, one thing really insinuating another, veneered by a tension that menaces the edge of every interaction.

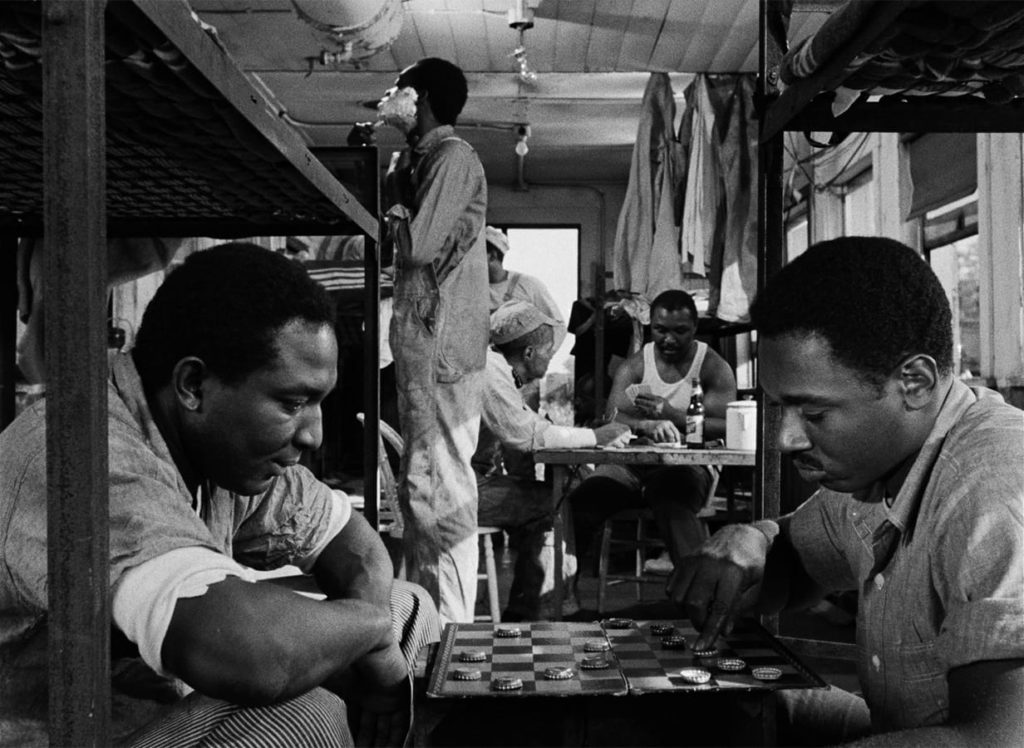

The film’s laconic tone gives the temporal breadth of Nothing But a Man a social insularity from the rest of the world, a remove that borderlines science fiction. For a production that took place during the height of the civil rights movement, released three months after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law, with Jim Crow (legally) on its deathbed, the film does not communicate the societal discordance of its time, at least not on the surface. Roemer, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, is concerned with a wider, cyclical perspective of how the current Black, American milieu has merely been refashioned from past forms of oppression, despite the legislative progress that was in place. Nearly all of the opportunities available to Duff to earn an honest living, by design, harken back to the work done by Black American slaves. Among this labor includes working on a railroad with a section gang, rather than a chain gang, working as a house servant for white people, or, quite literally, picking cotton. Ironically, working on the railroad provides Duff with the most amount of liberty and money; the work is backbreaking but he’s surrounded by other Black men (including a very young Yaphet Kotto, in his first credited role), whom he shares a camaraderie with. However that work is not consistent, and therefore mostly suitable for men who only need to support themselves. When Duff meets Josie, the lovely daughter of a preacher, he takes a lower-paying, but steadier, job at a saw mill in which he, and all the other Black men working there, are subject to their white coworkers’ “sense of humor” (read: racism). Between Josie’s father as a religious pillar in the community and these new Black men who work with him, Duff is exposed to an idea he’s just expected to tolerate: if you want to start a family, a Black family, that will further populate America, you will do so only under the conditions that Black people were allowed to have children in the past: to be of use to white people, to serve them, to preserve their way of life.

Beneficiaries of white supremacy understand that keeping the Black family fractured and disenfranchised is integral to holding on to the generational wealth they acquired through slavery. Legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (and the Voting Rights Act a year later in ’65) is a necessary factor for Black American liberation but is rendered moot if the group in question still suffers from mental colonization. Throughout Nothing But a Man, Duff Anderson is expected, by both white people and Black people, to acquiesce to the perception and conditions that Black people have suffered in America, and to say “thank you” for the opportunity to be lesser than. Because Duff refuses this inhumanity, he is viewed as a “troublemaker,” ungrateful and unable to provide for his family. Duff’s character, a mirror of sorts to the film’s formal presentation, is sensitive, patient, and thoughtful. He is the antithesis to these stereotypes. When imagining the reasoning behind Roemer’s stylistic and aesthetic approach, the etymology of Jim Crow, and the extreme contrast between the two, comes to mind. Thomas D. Rice was a white minstrel performer, famous for a a song and dance from 1828 called “Jump Jim Crow,” often shortened to just “Jim Crow.” Everyone around Duff, with the exception of Josie, becomes indignant towards him when he refuses to perform as he’s expected to, as Thomas D. Rice did, making his living in black face.

I suppose that Roemer was ahead of his time in the sense that he cracked the code to time travel, by proxy of applying documentary film techniques to the socio-economic conditions of the Black American South, and then presenting that portrait to a white America still suspended in their own nostalgia, for a time when Thomas D. Rice was a household name. Duff Anderson being stripped down to “nothing but a man” allows for a carceral purge of generational maladies, a rebirth of racial consciousness where his Blackness neither holds him back nor defines him.

Edited by Finn Odum