|Michael Wellvang|

Bad Lieutenant plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, March 10th, through Tuesday, March 12th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

X, Formerly Known As

By the mid-1980s, public perception of films “rated X” had shifted radically. First introduced in 1968 by the Motion Picture Association of America, the rating simply stated a patron should be at least sixteen to watch a particular movie. Now it just meant smut. So the MPAA sat down with theater chains, retailers, politicians, and community activists to discuss portrayals of sexuality and violence in the public space. They came up with a new rating: “NC-17,” or No Children 17 and under.

The rating took effect in September 1990. Seeing an opportunity, veteran producer Edward R. Pressman (Conan the Barbarian, Wall Street) partnered with exploitation director Abel Ferrara to develop a gritty crime thriller unlike anything that had been released before.

Given Ferrera’s knack for B movies, Pressman understood the director was most comfortable working within fewer constraints around sensibility. At the time, Ferrera was floundering following the release of his misunderstood film King of New York, which had undergone a costly re-editing process to maintain the lesser R-rating.

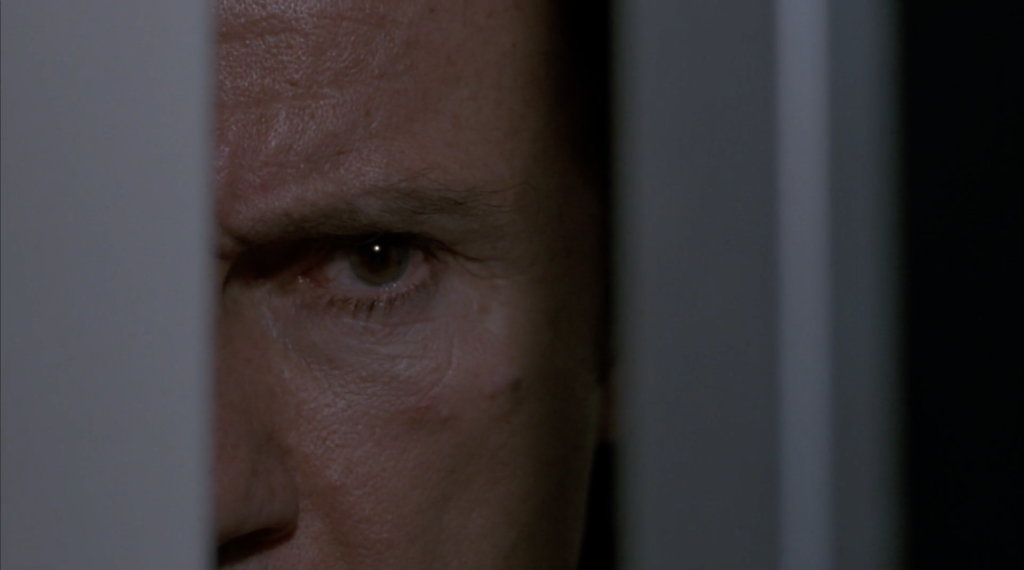

What Ferrera created with Pressman was Bad Lieutenant: an unflinching portrayal of a bad man wishing he was good. It was graphic, violent, even evil at times. But its lurid subject matter was all in service of a redemption story that defended Christian values in ways few films have, before or since.

There was just one problem: Blockbuster wouldn’t stock NC-17 movies. To make it into the rental chain, Ferrera had to cut, and somehow replace, over forty minutes of footage from Bad Lieutenant. It was a completely neutered film as a result.

Wayne’s World

Some readers may recall that independent video stores at the time tended to have a backroom cordoned off from view where the porn, horror, and otherwise shocking (in other words, X-rated) movies were kept. Blockbuster did not. Despite initially agreeing to purchase NC-17 movies for its rental fleet, the chain reneged a year later. And the man behind it all, owner Wayne Huizenga, didn’t even have a VCR.

How could this be? Well, he didn’t found the company. He merely invested in it after making a fortune with Waste Management Incorporated. He was attracted to Blockbuster because of the “family-friendly atmosphere.”

The thing is, Huizenga was no family man.

His ex-wife accused him of brutally assaulting her in front of their son, an accusation he didn’t dispute. And the San Diego District Attorney labeled Waste Management a criminal enterprise under his leadership. They had reason to do so: WMI associates warned the sanitation director of New Orleans he’d “wear cement boots.” Huizenga’s number two, Dean Buntrock, was accused by the Wisconsin Attorney General of threatening physical harm to competitors and their families. Furthermore, a slush fund was maintained throughout Huizenga’s tenure to keep local officials quiet.

It’s ironic that Huizenga would deny the uncut Bad Lieutenant from being included in Blockbuster’s slate of rentals, because he had a lot in common with the protagonist.

I’m the Bad Guy…Duh!

For starters, they’re about the same age: fifty-seven versus actor Harvey Keitel’s fifty-five at the time of shooting. They’re both Christian. Huizenga grew up in a conservative Dutch Reform household, and the lieutenant is Catholic. Despite their faiths, they have broken marriages with children. They even have the shared experience of spending a fortune on baseball (Huizenga owned the Marlins). But most importantly, they both did very, very bad things.

The difference is, one of them admits it.

From the first shot, we see why the film has its title. Bad Lieutenant opens with the unnamed protagonist parked in his car, waiting outside a house to take his kids to school. He’s angry, hungover, and clearly itching for a fix. When the kids finally jump in, they note that they were late only because “Aunt Wendy was in the bathroom.” He bites back, “Next time, you tell Aunt Wendy to get THE FUCK OUT!” As soon as they’re dropped off, he immediately snorts some cocaine, and goes to work—but not before placing a massive bet on the Mets.

Huizenga, on the other hand, projected nothing but good, wholesome fun. “We ran a clean shop” was an unsurprising refrain he’d repeat to the press. But he had his own familial troubles. As mentioned above, he was accused of beating his wife, Joyce. In her 1966 divorce court testimony, she described how they were eating dinner one night with their young son, who was having a meltdown. Huizenga flew into a rage, berating him for his screams. Joyce attempted to mediate the situation. In response, Huizenga allegedly hit Joyce with a chair and twisted her arm behind her back, to the point of bruising. He never challenged her testimony. In fact, he never even showed up for court.

Obviously, neither men are model fathers here.

The lieutenant’s days revolve around drugs, alcohol, gambling, and philandering. His attempts at parenthood amount to (tenuously) separating his addictions from his children, which nonetheless signify a commitment to a code of conduct. He’ll show up in the morning, take them to school, and get his fix when they’re not around—an accomplishment for an addict. Christianity teaches that a father is responsible for his family, and the lieutenant tries, however imperfectly.

In contrast, Huizenga rejected those teachings completely. He assaulted his wife while she was calming their son. Combined with his failure to appear at his divorce proceedings, never addressing the accusations of “extreme cruelty,” his actions indicate an abandonment of his family responsibilities.

AND YOU WILL ATONE!

No discussion of Bad Lieutenant is complete without mentioning the traffic stop sequence: following a crazed night of imbibing in every substance known to man, he learns a nun has been raped. He investigates the aftermath; first at the church, then at the hospital. He unexpectedly views her naked body on the gurney, exciting him. He’s ashamed of his reaction. That shame turns to anger, which he takes out on two women driving home from a nightclub. He pulls them over, steps up to the driver’s side window, and these two young women, clearly teenagers, are subjected to his commands: “Take off your pants,” and “Show me how you suck a cock,” are uttered nonstop for nearly ten minutes as he masturbates to completion.

Unfortunately for this essay, it’s impossible to find just one comparison from Huizenga’s life—there are simply too many.

But picture this: here we have a “clean” man presiding over a trash empire whose competitors would simply disappear, particularly in Chicago and Milwaukee. He bought a California company that was known to be run by the mob. Waste Management faced investigations in seventeen different states. His tenure was so riddled with criminal activity that investigations were still underway six years after he left the company. However, he never faced indictment. And thus, never recanted.

Unlike the garbage billionaire, the shame of sin doesn’t leave the lieutenant. It builds and builds, coming to a head when the nun won’t give up the identity of her rapists. “I already forgave them,” she says. The lieutenant cannot comprehend such a sentiment. The love she possesses for her enemy is so pure, so opposed to the life he lives, it cannot exist in this world run by the likes of him, let alone Wayne Huizenga.

Faced with true compassion, the lieutenant has no choice but to resign himself to his crimes. He prostrates himself before a hallucinated image of Jesus, crying out “I have done bad things!”

They’re the kinds of words we wish all bad men would say. Yet Bad Lieutenant is just a film, and this is real life, where people like Huizenga go free without following the values they claim to uphold. As hard of a watch as the film is, an accurate portrayal of Wayne Huizinga would be far worse—the bad guy wins, and is celebrated on LinkedIn to this day.

It certainly would not make it into Blockbuster.

Last Testament

Huizenga died in 2018, but the rental cut of Bad Lieutenant lives on. Even now, the radically redone version (forty minutes replaced!) is the only option on streaming platforms. It excludes the most potent sequences, such as the traffic stop, that give power to its narrative that the wretched can turn righteous—if they only humble themselves.

What does it reveal about our nation when horrible people can censor films that reflect their behavior as unsuitable for public viewing, solely because they are deemed inappropriate for minors? Perhaps we are not ready for adult conversations.

Or maybe they just don’t want to have them.

Edited by Finn Odum

Very interesting article. I did not know about Huizenga and the parallels of character was a fascinating take.