|Veda Lawrence|

The Piano plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, March 3rd, through Tuesday, March 5th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

“Whatever souls are made of, his and mine are the same.” For all my adoration for Austen, I must admit that she never wrote a single confession of love that comes close to rivaling even a throwaway sentence in Wuthering Heights in terms of romanticism and ferocity. That said, if one ever finds herself quoting Pride and Prejudice to a man, she may rest assured that she is safely ensconced in the realm of normal romance. If she finds herself quoting Wuthering Heights on the other hand…well, girl, be careful. Any man that brings to mind the spectre of Heathcliff is only to be admired from the distance of the hypothetical.

That said, as a literary matter, Heathcliff is perhaps the ultimate expression of the female gaze. An archetype created with the sole purpose of personifying the Victorian woman’s relationship with desire. He is the ultimate manifestation of everything that the prototypical “bad boy” represents (move aside Jess Mariano). To my friends who have argued that Heathcliff is a horrific love interest, I must refute those claims by pointing out that every attribute that they point out as detestable in Heathcliff (and there are many) is precisely what makes him the very zeitgeist of the female gaze (or at least, one particular manifestation of the female gaze. Sometimes we do envision good men—see Fitzwilliam Darcy.).

Yes, Heathcliff is horrifically violent, uncontrollable, flighty, and jealous. And each of those attributes speaks intimately to the female experience of the erotic—particularly the Victorian female experience. To Brontë, as the stand-in voice of the Victorian woman (obviously not a monolith, but for this essay, the sole voice under discussion), eroticism wasn’t unequivocally good or even desirable. She occupied a position that is comparable to that of someone enraptured in the present Evangelical purity culture. Female desire was supposed to be unheard of, and if it wasn’t, then at best something was medically wrong with you. At worst, you were practically monstrous.

What, then, were women supposed to do with the unfortunate reality that occasionally sexual desire pops up? And beyond the mere biological urge, what were women supposed to do with the entire experience of desire? Brontë creates a world that illustrates the dark tapestry of female desire, by creating a narrative centered around anxiety and intensity. Heathcliff himself stands as the object of this desire—in turn terrifying and seductive, the same confusing mixture of repulsive and appealing that the female viewer finds familiar in her own experience of desire. He represents how longing is tied up with fear—to desire is to transgress. In a world where women are punished for their desire, to experience it is an inherently dangerous affair, especially when women have little recourse in the face of actual violence.

Brontë acknowledges this in her exploration of Catherine Earnshaw’s struggle to choose the “respectable” Mr. Linton over Heathcliff, and with poor Isabella’s realization that Heathcliff, her husband, is an uncontrollable monster. To adequately present the female relationship to the erotic, it is imperative to present these themes—without them, it would be impossible to depict eroticism and sentiment from the female perspective.

A less-oft presented critique (and one which betrays the American unfamiliarity with the status and even existence of the Roma), but I think a critical one, is that of the uncomfortable racialization of Heathcliff. He is an inappropriate object for Catherine’s desire on account of his otherness, yet all the more appealing for he represents a life for her other than that of respectability. The exoticization of Heathcliff is deeply uncomfortable to me as a Romani person, yet I think this presentation is critical for understanding what Heathcliff means for Catherine. His otherness is a critical element of both his repugnance and his appeal.

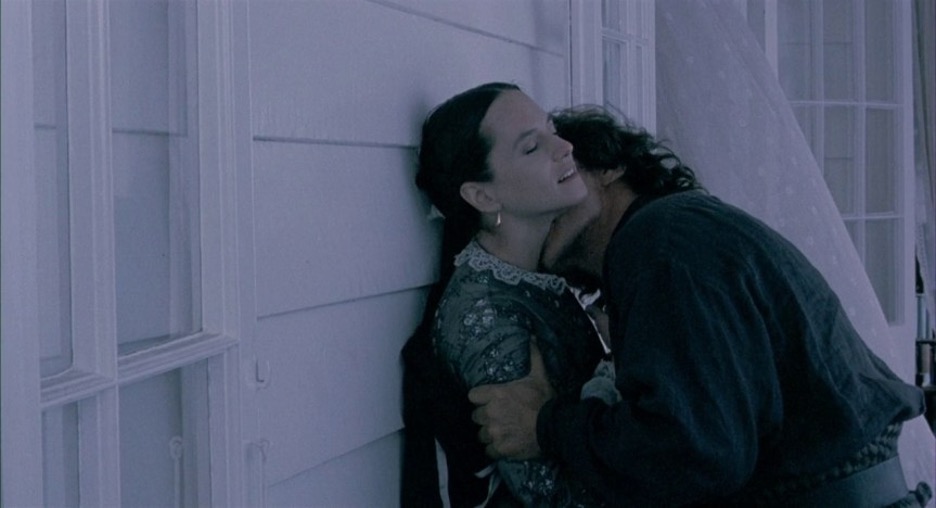

The Piano is evidence that those same themes pervade the modern female literary psyche as well. Heathcliff’s identity is bifurcated in The Piano, his status as an outsider is embodied by Ada, a newcomer to the island, and his racial ostracization is characterized by Baines. Baines further complicates the Heathcliff comparison, for instead of being a Romani boy raised in English society, he is by all accounts a white European. He rejects the status that Heathcliff was precluded from on account of his race, by adopting the traditions and tattoos of the Māori. He in a sense chooses the outsider status which was foisted upon Heathcliff.

Thus, his relationship with Ada takes on a nature at once distinct and inseparable from that of Catherine and Heathcliff. Catherine is forced to choose between being the respectable wife that society expects her to be, and following the consuming passion she feels for Heathcliff at the cost of her social standing. Of course, this desire haunts her even into her marriage, ultimately spelling her descent into hysteria—a visceral reminder of the anxiety that desire is monstrous, irrepressible. Similarly, Ada rejects the marriage to Alistair, which was her best chance at achieving some degree of social acceptability. Mute since childhood (a classic symptom of hysteria) and toting along a bastard child, Ada, like Catherine, has few options for securing a stable future for herself. And yet, even when she seemingly obtains security, her desire undermines this stability.

Catherine likewise is forced to eschew acceptability on account of her desire. She tacitly assents to her marriage with Edgar Linton, yet once in the union, she descends further into hysteria. She slowly starves herself to death until the birth of the child who represents the betrayal of her passion for Heathcliff finally marks her demise.

The Piano complicates this narrative. Flora is a reminder of Ada’s initial acquiescence to abject passion—motherhood for Ada is not the ultimate symbol of repressed passion, but rather a haunting reminder of love lost. And yet, it is Flora who ultimately betrays Ada’s tryst to Alistair. Flora represents the irrepressibility of passion—a child out of wedlock being the most tangible reminder of Ada’s former sexual transgression—and the catalyst for Alistair’s violent attempt to restrain Ada’s present adultery.

In a moment of sick irony, the birth of Catherine Earnshaw’s childhood buries her adultery with the death of Catherine—of course, it is exhumed with Heathcliff’s desecration of her grave and the memory of Nelly, but Catherine dies before she is forced to face the consequences of her sexual transgression. The Piano continues the gothic heroine’s narrative beyond the point of demise in Wuthering Heights. Ada “faces the consequences” of her sexual transgression, in doing so miraculously surviving and reaching a conclusion that marks a telos so close to victory that it almost betrays the gothic genre.

That is an overstatement, of course, for Ada’s relationship with Baines is almost inescapably shrouded by the veil of coercion that marked the beginning of their relationship. However, to dismiss this union outright on account of that coercion would be overly simplistic, and further dismiss Ada’s erotic agency.

Roger Ebert contends that Ada desired Baines from the start and her professed disgust with his advances was some sort of plot to protract their romance. This is certainly one interpretation of their romance, but I think a more compelling reading is one where his advances truly are never welcome. No offense to Mr. Ebert, but a man reading what is facially a coercive sexual arrangement as somehow desirable for the woman imposes a distinctly male perspective on the union and one which I think the film is wholly devoid of. Ada is clearly repulsed by Baines when he proposes this arrangement. To ignore this aspect of coercion is to remove a layer of sentiment from the film—an expression of how Ada’s entire life is restricted by the desire of men.

The more interesting transition here is the way that Ada’s view of Baines transforms from one of disgust to one of desire. Perhaps precisely because of her earlier repulsion, Ada finds herself drawn to Baines—in a way that is not wholly dissimilar to the way Catherine finds herself drawn to Heathcliff. Her desire is marred by coercion and the unacceptability of the union. Unlike Catherine, Ada does not deny herself her passions but rather gives into them and in doing so,ultimately recovers from her primary symptom of hysteria.

However, the consequences for her passions are meted out externally, unlike Catherine’s, which are experienced internally and psychologically. Alistair entraps and abuses Ada, cutting off her fingers and eventually sending her off with Baines. Ada’s body bears the consequences for her desire, but her mind is allowed to go free. The distinction between Catherine and Ada is paramount when Ada’s survival instincts will her to return to the surface after her beloved piano threatens to drown her. Unlike Catherine, Ada’s desire brings her back to life, while Catherine’s spells a loss of the very will to continue living.

Like Catherine’s ending, Ada’s is not uncomplicated. The audience must grapple with the fact that in finding her freedom, Ada has chosen the man who once manipulated and coerced her, the man whose advances, once reciprocated, ultimately lost her a finger. And yet he is also the only character, aside from Flora, who seems to have truly cared for Ada. Campion does not present us with an unequivocally happy ending, rather she presents an ending as close to triumph as a gothic heroine can be. She subverts the narrative presented by Brontë of a woman being consumed to death by desire and gives us a figure who accepts it and in doing so finds freedom. Baines, like Heathcliff, represents an amalgamation of inextricable female desire and anxiety.

Though Baines may have followed in the tradition of the gothic bad boy, his eloquence pales in comparison to Heathcliff’s. Until he can top, “Catherine Earnshaw, may you not rest as long as I am living. You said I killed you—haunt me then. The murdered do haunt their murderers. I believe—I know that ghosts have wandered the earth. Be with me always—take any form—drive me mad. Only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you! Oh, God! It is unutterable! I cannot live without my life! I cannot live without my soul!” Heathcliff’s domination over the title of ultimate manic pixie dream boy remains absolute.

Edited by Finn Odum