|Luke Mosher|

Werckmeister Harmonies plays at the Heights Theater Friday, February 2nd to Tuesday, February 4th . Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Béla Tarr’s slow cinema masterpiece Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) is a bleak and beautiful experience. It is exactly the kind of film that repertory theaters like Trylon were designed for. During the nearly 2.5 hour run time, you can’t check your phone or get distracted by your dog; you must sit in the theater and reckon with it. The film has images that will haunt you, a story that will captivate you, and a meaning that will befuddle you. It will show you the cosmos in the eye of a dead whale.

I often find the plots of slow cinema hard to follow (or totally incidental to the movie) but the narrative in Werckmeister Harmonies is relatively straightforward and quite engrossing: the quiet life of a small town is disrupted when a mysterious circus comes to town. The story starts small but builds to an apocalyptic conclusion, including a couple of late-film revelations that are genuinely startling. However, more often than not, the stories in Tarr’s films are not the point. They are only occasions to follow ordinary people to find out what their lives are like. From these simple human origins, Tarr extracts philosophical truths that expand to encompass everything. Human nature, life and death, religion and politics: no idea is too big to be considered. As Tarr puts it: “Film is not about telling a story. Its function is really something very different, something else. We can get closer to people, we can somehow understand everyday life, and somehow we can understand human nature, and why we are the way we are. How we commit our sins. How we betray one another. And what interests lead us.”1

Werckmeister Harmonies consists of a few characters who orbit each other like heavenly bodies in the solar system. The main character is János Valuska, the friendly neighborhood postman who likes keeping an eye out for his fellow townsfolk. The extremely likable János is something of a savior figure and is portrayed with a wide-eyed innocence by German actor Lars Rudolph. “How’s our János?” people greet him as he walks around the town making deliveries or checking in on his “Uncle” György Eszter, a family friend.

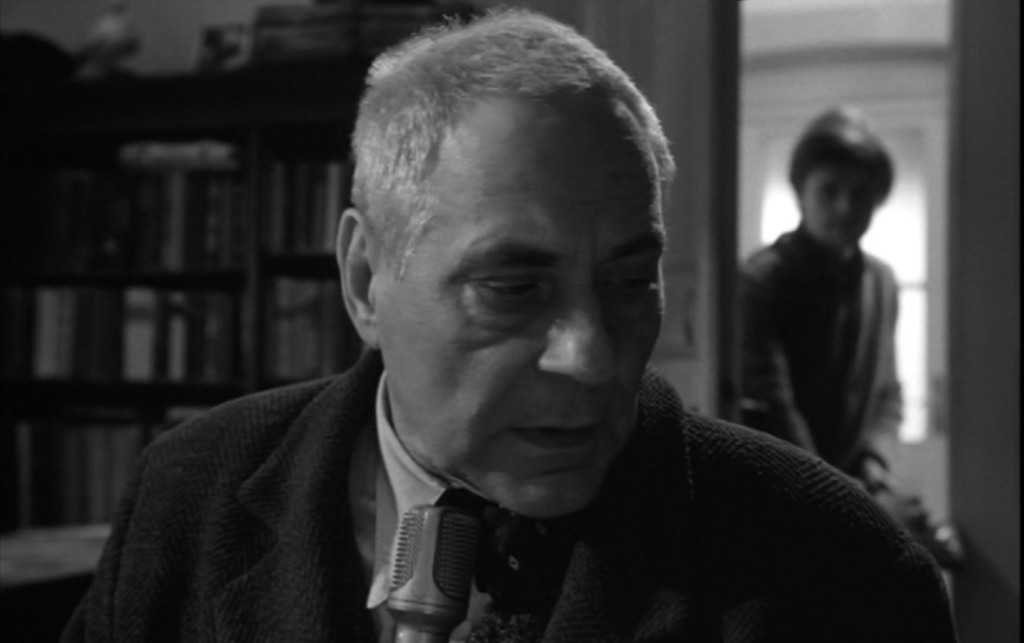

Uncle Eszter is János’s foil, a once-respected man in the community who long ago rejected public life to become a reclusive scholar of music. He lives alone, laboring to discover the true, hidden nature of musical harmony. Western music is built on a twelve-tone division of the octave—think of the twelve black and white keys on a piano from middle C to the C one octave higher. Andreas Werckmeister, a seventeenth-century German composer who lends the film its title, was an early advocate for the twelve-tone octave, and is namechecked by Uncle Eszter as a musical fraud who represents everything wrong with Western music.

Rejecting Werckmeister’s harmonies, Uncle Eszter invented a natural harmonic scale that corrects Werckmeister’s “mistake.” At one point he plays János a song on a piano tuned to his own scale, which just sounds like an out-of-tune piano. (For my fellow indie music fans out there, it kind of sounds like Mac Demarco playing classical music.) The two are counterparts, or maybe counterpoints: János represents harmony, and Uncle Eszter disharmony.

There is also Uncle Eszter’s estranged wife Tünde (Hanna Schygulla), the only character with any brains or ambition. She exerts a shadow influence in the town’s politics through her lover, the chief of police. When unrest breaks out in the town, she seizes the opportunity to exert political control through a hastily put-together committee led by Uncle Eszter.

The other two characters in our story’s orbit come from the mysterious circus. The circus is built up early in the movie as a grand spectacle, but when it finally pulls into town, it’s just a truck with a giant trailer—a sideshow at best. One character, so to speak, is a whale. The circus advertises it as “The Biggest Whale in the World,” but it’s just a stuffed, stinking carcass. In the film’s most memorable scene, one of those *chef’s kiss* “this is cinema” moments, János visits the circus to stare into the whale’s dead eye, looking for truth and beauty but finding only decay.

The other character from the circus is the “Prince,” who is advertised to speak to the town but never seems to appear. Rumors swirl that the prince has incited other towns to violence in the name of political revolution, and the townspeople eagerly await his emergence. This sense of imminent violence represented by the Prince gives the movie its feeling of impending apocalypse that drives the dramatic tension in the narrative.

The literary richness of the story, the characters, and the philosophical ideas at play speak to the film’s origin as a novel. Werckmeister Harmonies was adapted into a screenplay by László Krasznahorkai from his own 1989 novel The Melancholy of Resistance. Krasznahorkai is widely considered the greatest living Hungarian writer, and his collaboration with Tarr, considered the best living Hungarian director, is truly a writer-director dream team. The pair collaborated a total of six times over 23 years, Werckmeister Harmonies being the fourth of six. Their aesthetics complement and strengthen the other, the writing matching the direction perfectly. Krasznahorkai’s books are characterized by melancholy and madness, and his prose stretches sentences beyond their breaking point. Béla Tarr’s long takes are like cinematic adaptations of these endless sentences, which hypnotically twist and turn like snakes, or surprise us with an abrupt end.

The final thing that I’ll mention is, to me, the most delightful element on display in the film: Tarr’s signature cinematic element, the long take. The film is composed of 39 beautifully composed takes,2 each one good enough to be its own short film. Remember that scene from Goodfellas (1990) that everyone always talks about, the one-shot where Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco walk through the Copacabana nightclub? Small beans, my friend. The on-screen action is perfectly choreographed with the camera, which weaves between the action like a floating eyeball, always on the lookout for something interesting to show you. That’s why, despite the film’s nearly 2.5 hour run time, I promise you that you’ll never be bored. There is always something going on onscreen to look at, even when a character is just eating soup or getting ready for bed.

Watching Werckmeister Harmonies is both tortuous and pleasurable. Its surreal tone is almost impossible to put into words; it’s like a Dickensian social drama crossed with the Book of Revelation. I have tried to resist the urge to tell you what I think it’s all about because it’s something that needs to be experienced rather than explained, like a poem or a solar eclipse. Perhaps the best way to end is with a quotation from Yeats’s “The Second Coming,” a work I think about often when contemplating the film.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.3

- Special features interview in Werckmeister Harmonies, directed by Béla Tarr (2000; London, UK: Artificial Eye, 2003), DVD. ↩︎

- Ryan Lattanzio “‘Werckmeister Harmonies’ Trailer: Béla Tarr’s Elusive Masterpiece Returns to Theaters.” IndieWire (May 5, 2023). https://www.indiewire.com/news/trailers/werckmeister-harmonies-trailer-bela-tarr-4k-restoration-1234859229/. ↩︎

- William Butler Yeats. “The Second Coming.” The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats, 1989. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43290/the-second-coming. ↩︎

Edited by Finn Odum