|Abbie Phelps|

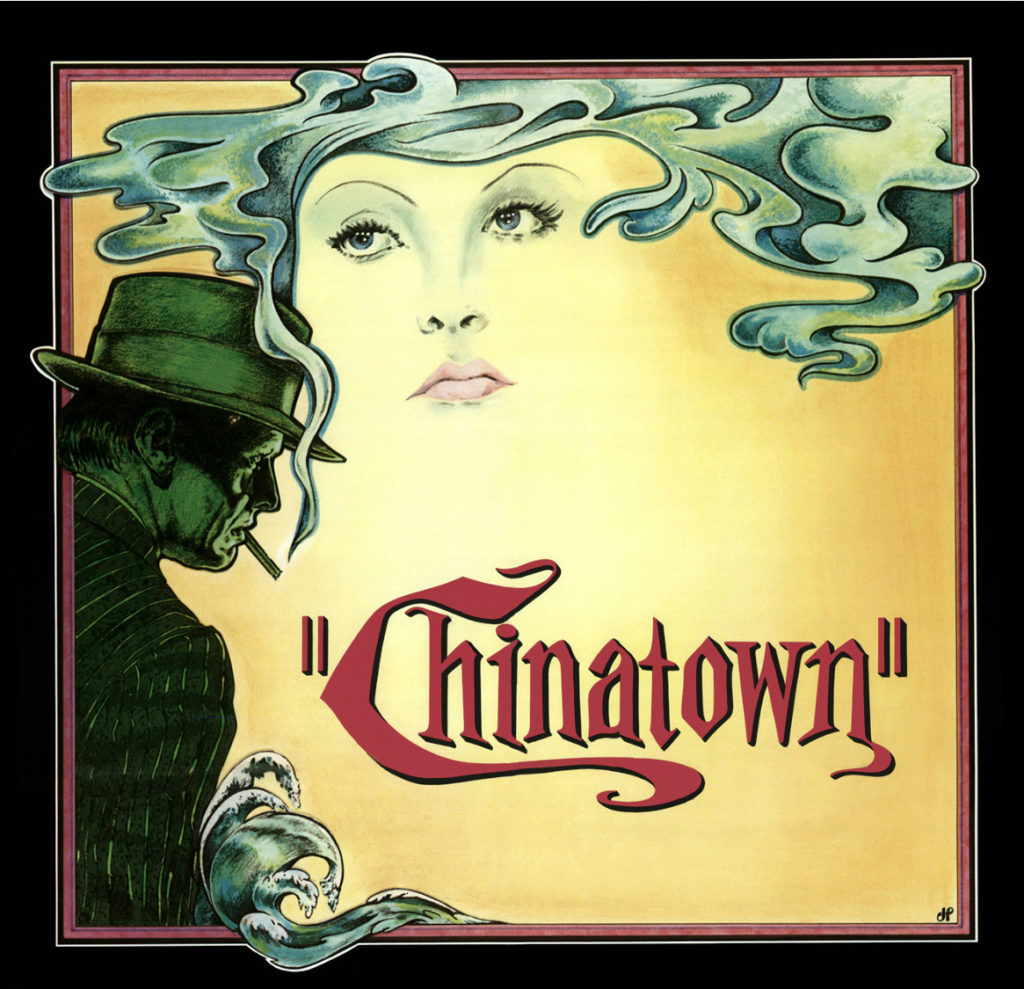

Chinatown plays at the Heights Theater Thursday, February 1st. Visit trylon.org or heightstheater.com for tickets and more information.

[Content Warning: rape, incest, CSA]

. . . during the interval in which he had experienced the two-world superimposition, he had seen not only California, USA, of the year 1974 but also ancient Rome . . . he had discerned within the superimposition a Gestalt shared by both space-time continua, their common element: a Black Iron Prison. This is what the dream referred to as “the Empire.” He knew it because, upon seeing the Black Iron Prison, he had recognized it. Everyone dwelt in it without realizing it. The Black Iron Prison was their world . . .

. . . The Empire never ended.—Philip K. Dick, VALIS1

Los Angeles, California, 1922. Evelyn Cross is fifteen years old.

Noah Cross, her father, has yet to recover from the death of his wife. In her absence, his grief has come close to consuming him. Evelyn, his daughter, makes his meals and lays his clothes out for him in the morning.2

One day, he rapes her.

Fifteen years later, his voice the clotted, strangled gurgle of some prehistoric creature slobbering for life, he’ll say, “I don’t blame myself. You see, Mr. Gittes, most people never have to face the fact that at the right time and right place, they’re capable of anything.”

Los Angeles, California, 1977.

Roman Polanski has never recovered from the murder of his wife. “What happened to me,” he said in the aftermath of Sharon Tate’s slaying, “diminished my contact, my rapport with people. It reduced me.”3

During the evening he takes Samantha Gailey to Jack Nicholson’s home, for what he calls a private photoshoot; she is thirteen years old.

Seven years later, when asked what he feels about his friend’s flight from prosecution, Nicholson will say, “Roman’s been the recipient of Western justice—that is, ‘Here’s a very complicated moral issue, so, we heat you up until you get out of town,’ which he did . . . The tragedy is that I was watching Roman fall in love with America after some difficult times here. His situation is a very interesting case of what notoriety can do to you. I always felt Roman was exiled because his wife had the bad taste to be murdered in the papers.”4

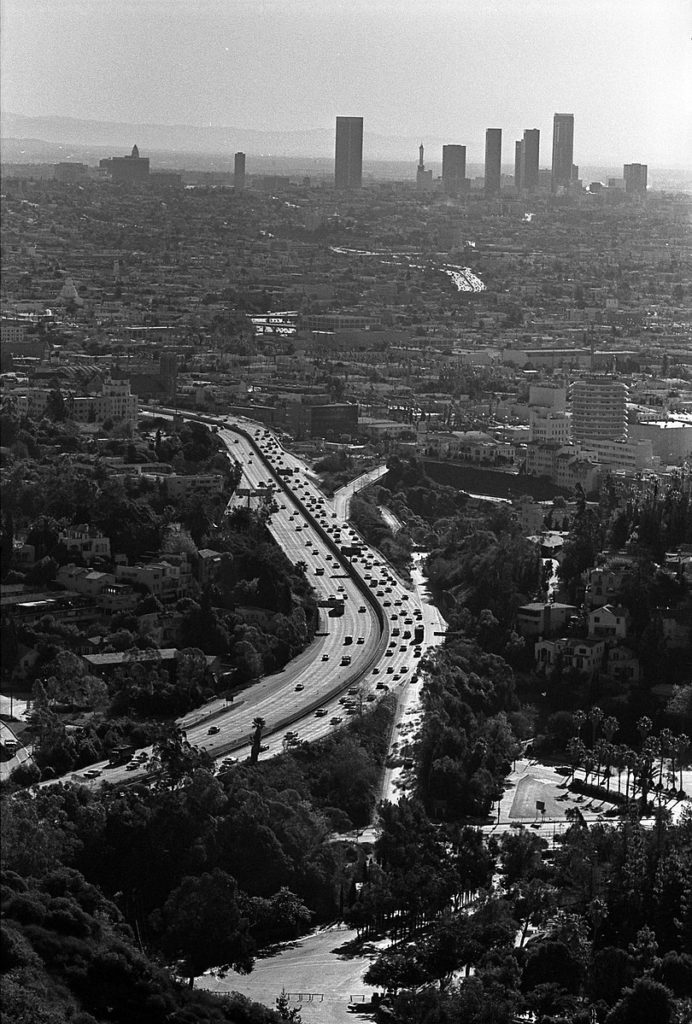

It would perhaps have been more accurate for Nicholson to say that Polanski had fallen back in love with Los Angeles—the city that had murdered Sharon Tate, whose roots in rape and violence and graft he’d documented in exquisite detail in Chinatown, but whose sparkling exterior put the lie to all the blood flowing in its water. It was a paradise whose grandeur was all the greater for the fact that it was an illusion—the sheer amount of suffering that has been added up day by day, decade by decade, to maintain that illusion is enough to inspire awe in anyone.

When Noah Cross looked forward from 1937 to the rest of the century—when he spoke lovingly of “the future, Mr. Gittes, the future,” his legacy for all time—he gazed upon the same town Roman Polanski would come to love.

To say that Polanski, Robert Towne, or any of the principal creative hands in Chinatown made a movie that was “about himself” is to give in to the cheap and easy—the Noah Crosses of this world never consider themselves to be such. Nor is it a movie about the “real” Los Angeles—the city’s roots were first given stolen water to lap up not in 1937 but at the beginning of the twentieth century, not by any sort of Cross analogue but by William Mulholland, whose Chinatown equivalent Hollis Mulwray is recast not as the villain he was but a kind of martyr. The black rot that festers in the heart of the film is not fact or autobiography; Chinatown the film is a potboiler dressed up with some historical trappings and some class, not some kind of twisted confession.

And yet the patterns ripple outward, zigzagging back and forth through time. Polanski flees the country, then continues to enjoy a long life making films with relative impunity. Nicholson beats a sex worker hard enough to inflict brain damage, then continues to enjoy a long life making films with total impunity. Robert Towne, out of his mind on cocaine, physically and emotionally abuses his wife, then gets joint custody of their child—Katharine, whom he named for Evelyn Mulwray’s daughter.

Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that, whether they meant it as self-portrait or not, the authors of Chinatown became its living image. It’s a film dizzy with recursion, with pairs of mirrors distorting the same image back and forth to the infinite. Jake Gittes, Chinatown cop, “thought [he] was keeping someone from being hurt,” only to ensure they were hurt. A decade later, in Chinatown, it happens all over again. Noah Cross takes his daughter Evelyn, suffering from the death of her mother, and does the unspeakable to her. Fifteen years later, he snatches up his daughter Katherine, her mother shot dead in front of her. We don’t have to see what he’ll do to her; we know.

As a story, it’s singularly bleak, but it’s not unique. In the final shot of the picture, as Gittes stares off into eternity, he’s aware of this—he knows that what he’s just seen is part of a cycle that will happen over and over until he’s dead, and it’s that inevitability that finally breaks him. Just so, Roman Polanski, the most infamous moral abyss in the history of moviemaking, is merely one of thousands and thousands of powerful men who’ve weathered their own atrocities and then kept right on shooting—not only is his evil not unique, but it’s not even unique among the people who helped to make Chinatown.

It doesn’t really matter whether the year Los Angeles first stole its water was 1905 or 1937. In the last century, the American West has erected dams by the thousands to choke rivers to trickles, redirected enough irrigation water to destroy habitat after habitat, scoured an entire continent’s ecosystem bare to prop up rich farmers and movie stars. The pact that brought the town to the water wasn’t the moment that sealed the city’s fate; it was one of a thousand dooms that brought a thousand more dooms to bail them out.

1905, 1922, 1937, 1974, the present day. Slap whatever date you like on it—temporal labels are as illusory as the mirage of the city rising from the desert. It is always happening—it will always be happening—over and over again, the faces of victims and perpetrators blurring into one smear of violation and ruin. In essence if not in allegory, Noah Cross is Roman Polanski is Los Angeles, is, is, is, stretching backward into nothingness and forward into the void. Chinatown is a nexus point not because of any special curse, but because, of the thousands of black holes eating up Hollywood, a few simply happened to be there at the right time, at the right place, to make a monument to the city of their dreams.

At the right time, at the right place, some people are capable of anything.

Edited by Finn Odum

- Philip K. Dick. VALIS (Boston: Mariner Books, 2011; first edition 1981). 47, 46. ↩︎

- Per Towne’s third draft of Chinatown, in dialogue that would not make it to the screen. “. . . he had a breakdown . . . the dam broke . . . my mother died . . . he became a little boy . . . I was fifteen . . . he’d ask me what to eat for breakfast, what clothes to wear! . . . It happened . . . then I ran away . . .” https://www.public.asu.edu/~srbeatty/394/Chinatown.pdf ↩︎

- Bernard Weinraub. “If You Don’t Show Violence the Way It Is . . .” (interview). New York Times Magazine (December 12, 1971). https://www.nytimes.com/1971/12/12/archives/-if-you-dont-show-violence-the-way-it-is-says-roman-polanski-i.html. ↩︎

- Nancy Collins. “The Great Seducer: Jack Nicholson” (interview). Rolling Stone (March 29, 1984). https://web.archive.org/web/20081021095326/http://www.jacknicholson.org/1984RollingStone.html. ↩︎