|Timothy Zila|

Blade Runner: The Final Cut plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, January 14th, through Tuesday, January 16th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

There’s a knock on the door or a ringing phone or, quite often, a stranger waiting in the detective’s office. The noir protagonist doesn’t seek trouble out; trouble seeks him. So it goes in Chinatown and The Maltese Falcon. And so it goes, too, in Blade Runner.

When we meet Deckard he’s reading a newspaper, trying to stay out of the rain while waiting for a spot at an outdoor noodle restaurant. He hasn’t had more than a couple bites when he’s pulled away by a grizzled, nearly wordless police officer (the iconic Edward James Olmos, in a small but thematically crucial role), who isn’t asking Deckard to come with him; he’s commanding it.

The opening described above could belong to any PI-starring noir in existence. One of the crucial features of the genre is its reluctant protagonist—a man or woman who’s just out to get by. They want some noodles and liquor in their stomach. They aren’t trying to uncover the seedy underbelly of society. They’re not out to out corporations or politicians or celebrities. What they do is merely in the service of their duty to their clients, and their clients pay in cash. You can think of it as the reverse of the “investigative reporter” movie, where a driven reporter risks their career and life in search of something higher—call it the truth or call it “the story.” The noir protagonist doesn’t seek the truth so much as stumble upon it. And then stumble again. That’s something Rick Deckard is plenty familiar with—both literally and metaphorically.

The influence of noir on science fiction is a relatively known entity at this point. The Matrix and Dark City immediately come to mind. The former was a massive hit, and the latter is something of a cult classic—though well-known among film lovers, I think. But was Blade Runner the first sci-fi film with a prevalent influence from film noir? The answer is no. A quick Google search suggests several obviously-earlier-than-Blade Runner possibilities, including Jean Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965), though there are earlier films containing both noir and sci-fi elements as well. Regardless, Blade Runner is unquestionably the most iconic early example of a sci-fi film with noir trappings. Or perhaps it’s the other way round: a noir with sci-fi elements.

Part of what makes Blade Runner so special (in addition to the world-class costume and set design, cinematography, direction, and the eternal Vangelis score) is the thematic connection point between its noir protagonist and the world of the film at large—a Los Angeles that’s mostly abandoned and perpetually raining, where nearly all but the genetically defective or incredibly poor have already moved off earth.

There’s a sense in some noirs that it’s mostly the protagonist who’s getting drubbed by the world—constantly misled and manipulated by forces who spend most of the movie off-screen. This is the case in Farewell, My Lovely, a 1975 adaptation of the 1940 Raymond Chandler novel, where the plot, explained from the endpoint of the movie, is so obvious it is almost laughable. But the details of the story themself serve as a kind of bewildering red herring. In Farewell, My Lovely one of those details is a physically massive and dimwitted bank robber named Moose Malloy who’s newly out of jail and looking for his old sweetheart. It seems so improbable he’d have such a gorgeous girlfriend, that we spend a lot of time fixating on the details without realizing what’s really going on. The result is that Philip Marlowe (as well as the audience) remain ignorant of what’s really going on until the very end.

This beleaguered motif is notably embodied in what I think of as the “stoned” sub-genre of noir—films like Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice and the Coen brothers’ The Big Lebowski. Only one man’s door gets kicked in, after all. Only one man’s rug is soiled—and it belongs to the sad sap who unwittingly, step by step, uncovers the conspiracy at the heart of the movie.

This is not the case in Blade Runner. It’s true that Deckard endures his share of emotional and physical violence throughout the film, but look at the world around him! It’s hard to say he’s uniquely persecuted when everyone in the film—sans Tyrell in his ivory tower—is living in the ruins of the past.

This brings me to the single thematic element that I think makes Blade Runner such a timeless and unique film: its nearly complete uninterest in making any of the sci-fi elements seem cool. The replicants themselves—while technologically advanced and special (to use terms like these is, of course, to speak of the replicants the way the Tyrell Corporation speaks of them—as products, not as life forms)—are presented as drab. Even our introduction to the replicants is banal: the interview in which the Voight-Kampff test is performed.

The film has a quiet, muted character. Without narration (as the film is presented in the Final Cut), Blade Runner almost doesn’t seem to care if you’re watching. The film has an observational quality; the characters move around the scene as if we are not watching them. If it’s unclear what they’re doing or why, the film doesn’t try to explain itself. They are simply there—just as the world the film presents is simply there. Nothing is made of how the world got to be the way it is. The world simply is, and the film simply is too. There’s a meditative quality to the long wordless stretches of the film where very little happens, and to the extent that the film asks questions it largely does so implicitly. You may wonder what happened to make the world this way, but the film will not tell you.

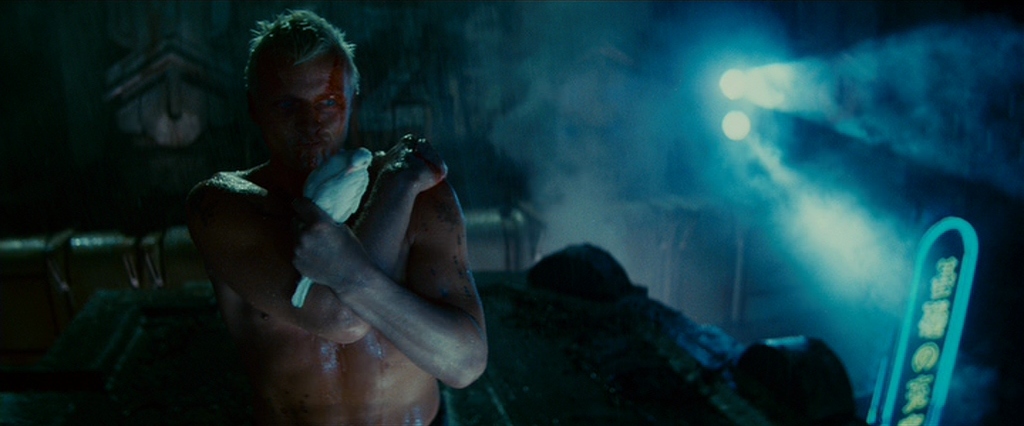

Now, it is true that Ridley Scott revels here and there in the physical attributes that make the replicants superhuman: say, the ability to submerge a hand in boiling water and remain unscathed. But most of the spectacle is held until the movie’s climax, where Roy Batty physically destroys Deckard in a series of sportsman-esque challenges that veer firmly into the territory of torture. The replicants are physically superior to humans, no doubt, except in one crucial regard (the linchpin of the plot)—they’ve been designed to die.

Which is ironic, since the future world depicted in Blade Runner is quite clearly already dead. At the beginning of the film, when the police captain tries to recruit Deckard to “retire” the replicants, Deckard tells him, “I was quit when I come in here, Bryant, I’m twice as quit now.” That’s a description that seems apt for the larger world too—twice quit.

And yet, the replicants themselves want to live. If the humans are living in what they know is the graveyard of the earth that used to be, the replicants post-date that earth. This is the only earth they’ve ever known, and they want to stay on it just a while more. In that way, they’re not so different than a lonely blade runner stumbling along, trying to stay out of the rain and grab something to eat.

Edited by Finn Odum