| Luke Mosher |

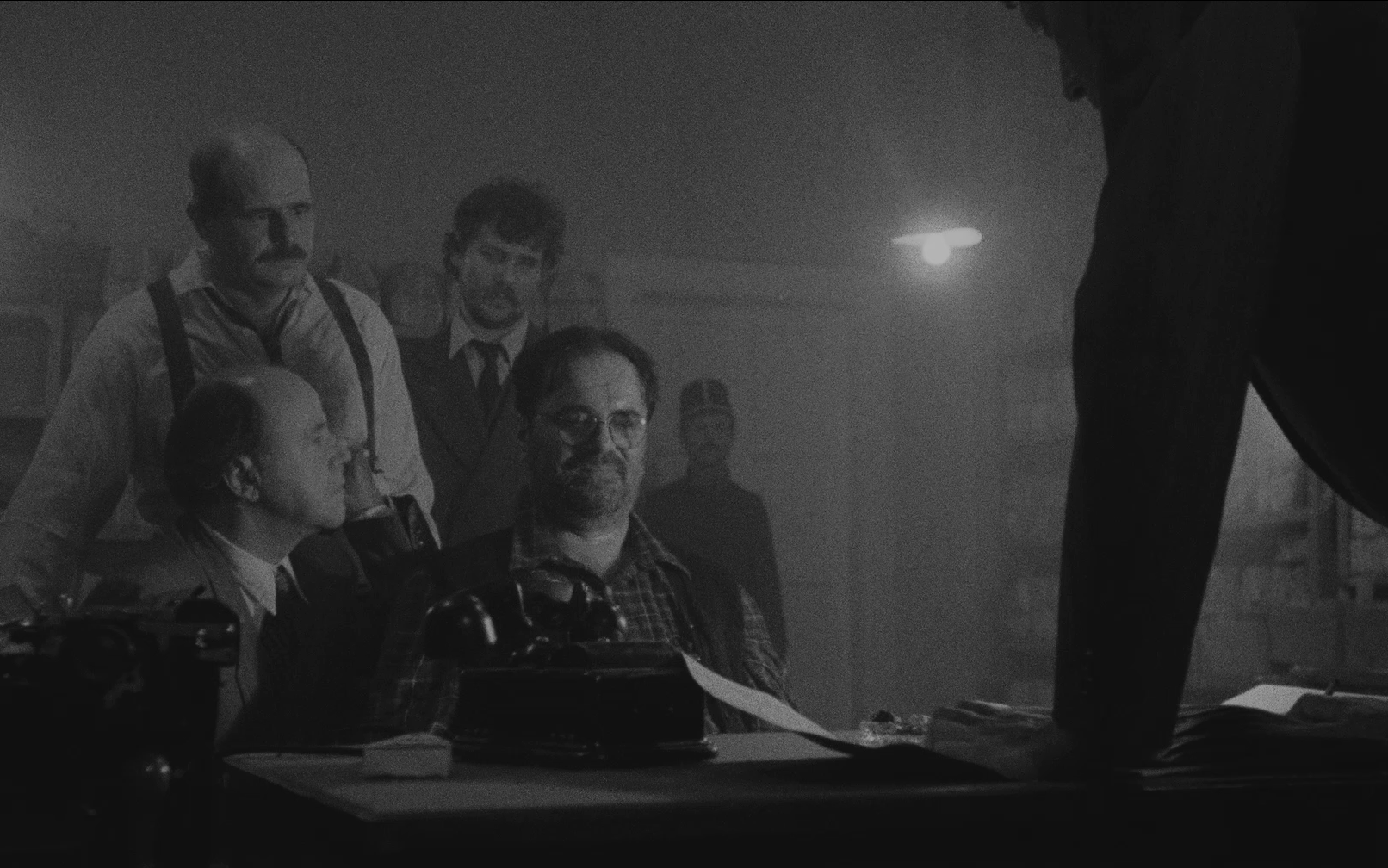

The lead detective Felügyelõ, played by Péter Haumann with a strange emptiness.

Twilight plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, November 17th, through Sunday, November 19th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information

György Fehér’s Twilight (1990) opens with an aerial shot over the forested Hungarian mountain Csóványos while an ambient song drones in the background like the hum of an airplane. On the ground below, two dark figures ride in the back of a car, speaking in low voices. They join a group of policemen at the top of a wooded hill, near the foot of a tall cross, where an eight-year-old girl’s body was discovered—the most recent in a string of child murders. There are no suspects or theories. At the ridge of the hill they stand, darkly silhouetted against the gray sky, while they wait for someone to take charge. Nobody does.

This somber scene sets the tone for the rest of Twilight, a Hungarian detective film that’s something of a lost relic for those of us devoted to the near-religious experiences of slow cinema. Held in high regard in arthouse circles and obscure Letterboxd lists, the film never had a U.S. release in theaters or on home video before its current theatrical run,1 and was nearly impossible to track down for the last thirty years—a fate that, coincidentally, mimicked its themes and story. I could find only a single mention of its original release in the U.S. press, a short review whose opening line sums up the movie nicely: “[Twilight] is an agonizingly slow but beautifully photographed thriller in which every shot seems to take forever and the story has the peculiar quality of never advancing.”2

The police interrogate the man who discovered the eight-year-old’s body as a suspect. In Twilight, no good deed goes unpunished.

Twilight, as a time period, is ambiguous: it can refer to both the time just before sunrise, or just after sunset. Metaphorically, it is the liminal period before things get better, or get worse. Throughout Twilight, we don’t know which way it will go—this is the “peculiar quality” the lone film critic points out. We are suspended in the in-between state of both-and, not either-or. It’s this strange in-betweenness that gives the film its otherworldly feeling. Twilight has the distinct characteristic of being both the weightiest film imaginable and not meaning anything at all.

The film’s plot is simple: a policeman investigates a child’s murder. Péter Haumann plays the lead detective Felügyelõ, who is assigned to the case shortly before his retirement—another twilight period of sorts. Haumann plays him with a strange vacuousness, as if he were conducting the investigation entirely inside his own head. Fehér directed Haumann to strip down his acting to the bare minimum, and at times told him: “Don’t do anything.”

Felügyelõ following up on a lead. Many shots in the film are framed through windows or doorways.

This narrative inertia is felt throughout the story, upending traditional genre conventions that define the detective figure by his pursuit of justice. Felügyelõ, by contrast, is defined by his inaction. His investigation seems to lead nowhere. The lead suspect is an unknown man described by the children of the village as the giant, or the wizard—a mysterious figure that lends the film a strange fairytale quality. Like the villain in a folktale, the giant lures children into the forest with candy, where they disappear. Felügyelõ is baffled by this story and has no idea where to begin his search; it’s like trying to hunt down the witch who eats Hansel and Gretel after hearing about her in a tall tale. Somewhere along the way, he seems to lose the plot—and so do we. If you have trouble following the story, the film has been successful for you. Sometimes there are lulls so long that you may forget what’s even going on in a given scene, but that’s all part of the game: the gradual erosion of meaning until nothing’s left but the bleak landscape where it always seems to be misty or raining, and the people unlucky enough to live there. The uneasy gap between futility and meaning, mystery and solution—this is the liminal space the film lives in.

Fellow cinema fans will be interested in Twilight because of Fehér’s connection to his friend and collaborator Béla Tarr. Tarr is one of the most renowned directors of slow cinema, a film movement whose name, for once, tells you exactly what it is. Tarr worked as a consultant on Twilight. In turn, Fehér helped produce Sátántangó (1994) and script Werckmeister Harmonies (2000; keep your eyes peeled—Trylon will be playing this film February 2-4, 2024). If you are familiar with Tarr’s work, Twilight will feel like long-lost kin. It is textbook slow cinema: beautiful black-and-white cinematography, long takes, bleak-yet-picturesque framing, sparse dialogue, and lengthy stretches of inertia punctuated by moments of surprise. Other comparisons to Twilight’s detective story might be the moody Nordic noirs like Insomnia (1997), where the detective’s interiority is as important as bagging the bad guy. But similarities to other detective films end there—Twilight is truly sui generis, borrowing elements from slow cinema and the detective genre without being shackled by the conventions of either.

The statue of a Turul, a mythological hawk that is a national symbol of Hungary.

Twilight is based on the novel The Pledge: Requiem for the Detective Novel (1958) by the Swiss writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt. If the novel’s title sounds familiar, you may remember Sean Penn’s 2001 adaptation The Pledge, which starred Jack Nicholson as the central detective. Dürrenmatt had used an earlier version of the story in a screenplay for a film called It Happened in Broad Daylight (1958), but was unsatisfied by the trite elements of its story. He expanded it into The Pledge, which is much darker and borders on the existential, more like the novels of Albert Camus or Jean-Paul Sartre. The novel was an international hit and has been in print since its first translation into English in 1959. Since then, it’s the novel that’s the preferred version of the story. Something about it hit a universal chord, as it’s been adapted seven times (so far) into films from the U.S., Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, and India. Fehér’s Twilight is the second of seven.

One crucial element to Twilight’s dark, moody quality is the score, which is officially credited to János Réti, but has another source that’s so unexpected I can’t help but share its story. The haunting song with the unearthly choir that plays over the opening scene and recurs throughout the movie is a sample of the Kate Bush song “Hello Earth,” of all places, from her 1985 album Hounds of Love.3 This is the same album that gave us “Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God)”—the song that Stranger Things season four relaunched into the cultural zeitgeist of summer 2022. It’s so charming to me that Twilight, a stone-cold serious arthouse film, uses a song by Kate Bush, the ethereal goddess of pop music. Bush first heard the choir section that’s used in Twilight in another arthouse favorite, Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), where it plays over the opening credits. The song is an old Georgian folk tune named “Tsintskaro,” but there were no credits for the song in Herzog’s movie, and Bush couldn’t find sheet music for the film’s score either. For her recording of “Hello Earth,” she hired composer Michael Berkeley to phonetically transpose the song from Nosferatu into sheet music that could be sung by a choir, and directed him to make it sound odd, surprising, like it came from another world. The resulting “Hello Earth” sounds like the Georgian original, but the vocal parts are actually sung in a made-up language. In other words, the song is not from any language of Earth—it is literally unearthly music. Somehow, this strange history fits entirely with the otherworldliness of Twilight.

Kate Bush’s “Hello Earth,” the unexpected source of the haunting song that plays throughout the film.

If you’ve never seen slow cinema before, this is as good an entry point as any. But prepare yourself to be patient, because it will feel like you’re just “waiting for something to happen,” as one character puts it. Counter to conventional film editing (which cuts every few seconds), Twilight’s shots last upwards of several minutes. Slow cinema isn’t realistic, exactly. It’s not trying to convey the slowness of real life, like a Yasujirō Ozu slice-of-life drama, or attempt documentary-like verisimilitude like the Italian neorealists or some of the French new wave did. Slow cinema is exaggeratedly slow. People act deliberately languid and scenes take way longer to play out than they would in real life. Slow cinema is more like meditation. It is, as Andrei Tarkovsky puts it in the title of his memoir, “sculpting in time.” It takes practice, but if you’re able to still yourself into a quiet headspace, slow cinema has some of the highest highs that movies have to offer. The patience required for slow cinema has often reminded me of what David Foster Wallace writes about the rewards of attention in his novel The Pale King: “It turns out that bliss—a-second-by-second joy + gratitude at the gift of being alive, conscious—lies on the other side of crushing, crushing boredom.”

Twilight opens with a bird’s-eye view of the Hungarian mountains, and halfway through the film, we finally see the bird. In a scene where Felügyelõ revisits the location of the crime, close to where the girl’s body was found, stands the statue of a Turul, a mythological hawk who holds a sword and looks out over the rolling mountains. In Hungarian legend, the Turul led the Magyars to the land where the country was founded in the 9th century.4 It served as a symbol of guidance and protection for over a thousand years. Now, however, a terrible atrocity has been committed under its watchful gaze, while it looked on, doing nothing. At the end of the film, the aerial shot repeats, as if the Turul were flying away. It is abandoning a country where citizens devour each other, where a village cannot protect its children from the evil that lurks in the woods, and where dawn never breaks. A world stuck in eternal twilight.

Bibliography

1 Earlier this year, Twilight received a 4K restoration by Hungary’s National Film Institute. The UK label Second Run put out a Blu-ray of Twilight from this restoration, which is how I was finally able to see it. We live in a golden age of restorations and boutique Blu-ray labels, and shouldn’t for a moment take it for granted. All stories and factoids about the movie come from the Blu-ray special features and the insert booklet, with an extremely helpful essay by the writer and filmmaker Stanley Schtinter called “The Sun of Yesterday is Borne on a Black Stretcher,” which was the only authoritative writing I could find on Twilight (besides reviews of its theatrical rerelease), despite hunting high and low. Twilight, directed by György Fehér (1990; UK: Second Run, 2023), Blu-ray.

2 Variety, “Film Reviews–Szurkulet,” 1990, Los Angeles: Penske Business Corporation.

3 For a longer version of this story, which is fascinating, see Michael Berkeley, “Kate Bush rules, OK?,” The Guardian, October 11, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2005/oct/11/popandrock.

4 Manabu Waida, “Birds,” in Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd ed., ed. Lindsay Jones, 947-949, vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005).

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon